Ukraine’s Gen Z just saved democracy with cussing and poetry

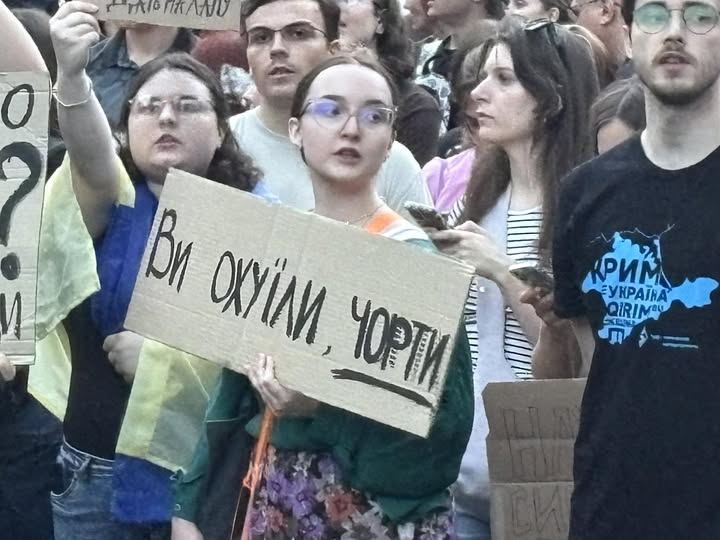

“Fucked up reformers!” screamed the sign of 18-year-old Polina, the girl with the green hair. Her companion’s metaphorically shouted “CUNTS” in huge green letters. Teenage profanity filled every corner of the first large wartime protests engulfing Ukraine’s capital.

It could have been any Gen Z rebellion against the system. And in a way, it was—against a system where President Zelenskyy gutted Ukraine’s anti-corruption bodies over just 72 hours. Except it was also a protest for a system—the one Ukraine dreamed up during the Euromaidan revolution in 2014.

“I don’t give a f*ck,” Polina snapped back at criticism over the protests’ expletive language. “Swearing allows you to express an opinion and is part of the freedom of speech. Get it?”

Prudes on Facebook scolded protesters like her: it was beneath Ukrainian national dignity to devolve to such unholy vocabulary.

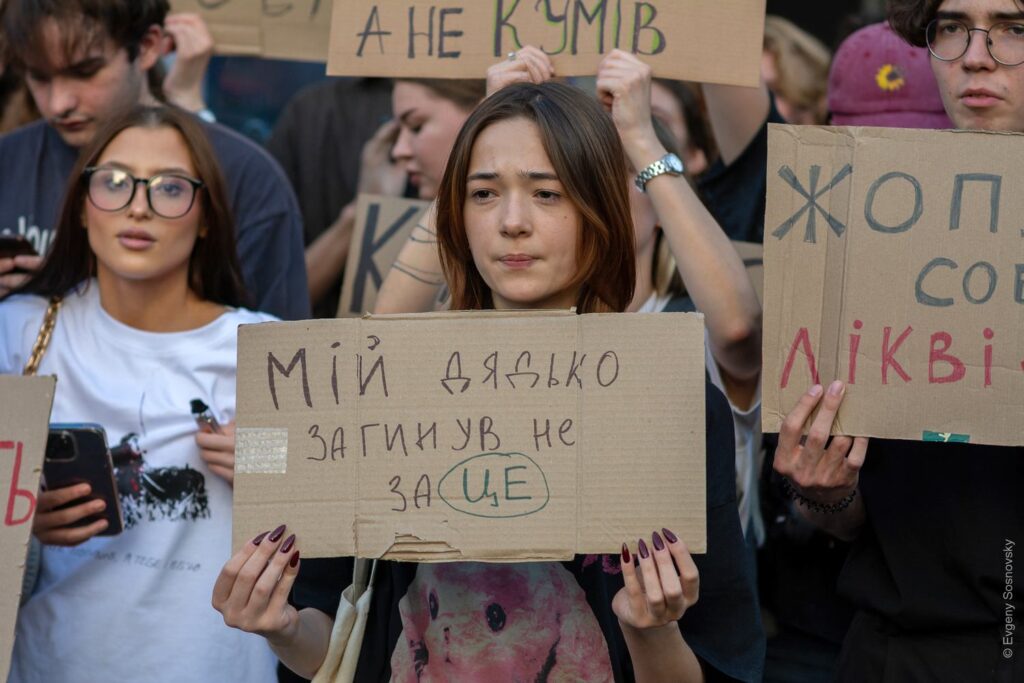

Yet there she was, a first-year student of Ukraine’s top university, one uncle killed during the 2014 protests where Ukrainians rebelled against a pro-Russian president’s U-turn on EU integration, and another uncle killed fighting the Russian invasion, unapologetically demanding political accountability from Ukraine’s president.

“We know our history, we know why this happened. We are fighting for our freedom from Russia. We are against Ukraine turning into Russia from the inside. So, NABU should be an independent institution,” she said.

Polina encapsulated the main demand of the protests—that a law to bring Ukraine’s anti-graft agencies under the control of a presidentially appointed prosecutor is repealed.

Tens of thousands of people like Polina, holding a sea of cardboard signs, may have just saved Ukraine’s democracy.

The 20-somethings who organized a revolution in 24 hours

Protesters against corruption in Kyiv. Photo: Evgeny Sosnovsky

Twenty-three-year-old Zinaida Averina never expected to become the architect of Ukraine’s first wartime democratic uprising. When parliament rushed through legislation gutting anti-corruption agencies on 22 July, she created a Telegram chat for protesters that exploded to over 2,000 people within hours.

“The only person who filed an application with Kyiv city administration for the 23 July protest was my friend Sofi Wisdom, also 23,” posted activist Anastasiia Bezpalko. “None of the organizations or opinion leaders who called for protests did this basic work. The girls showed leadership in a crisis and took enormous responsibility.”

The chat became a masterclass in grassroots democracy. Participants debated protest demands, coordinated with police, organized snacks and water stations, and—uniquely for a political movement—created separate threads for memes and hookups. “What could be sexier than a clear civic position?” joked one organizer. “We need to solve the demographic crisis!”

Many signs cheekily declared “This cardboard is paid for”—a stab at conspiracy theories claiming Western funding behind the protests’ eruption.

But the most remarkable thing happened on the streets. “Two very young people, eyes shining with excitement, look at the crowd,” overheard researcher Anton Senenko. “Katya, this is our first Maidan!” one exclaimed, hinting at the protest pedigree of Ukrainians—each revolution happens on Kyiv’s Independence Square, Maidan Nezalezhnosti. They kissed.

That romantic moment captured everything about this movement. For Western teenagers, political engagement often means attacking institutions. For Ukrainian Gen Z, it meant defending them—while falling in love doing it.

“I defended Zelenskyy against Trump’s dictatorship accusations. Now I can’t,” says Ukraine’s top corruption fighter

Why swearing terrified the authorities more than anything

Critics fixated on the protesters’ colorful language, missing why it was so politically effective. Oleksandr Rachev explained the strategy behind the swearing.

“When you tell authorities ‘you’re wrong,’ you stay within a model of respect that doesn’t frighten them,” he noted. “When you say ‘you’ve lost your fucking minds,’ it means questioning their very legitimacy. And that scares them.”

The profanity served another function: mass appeal. “Swearing is considered the language of ‘ordinary people,'” Ravchev continued. “University professors and activists don’t swear—that’s why they stay in their intellectual bubble. Swearing is a bridge between creative youth protesting and ordinary voters who actually vote.”

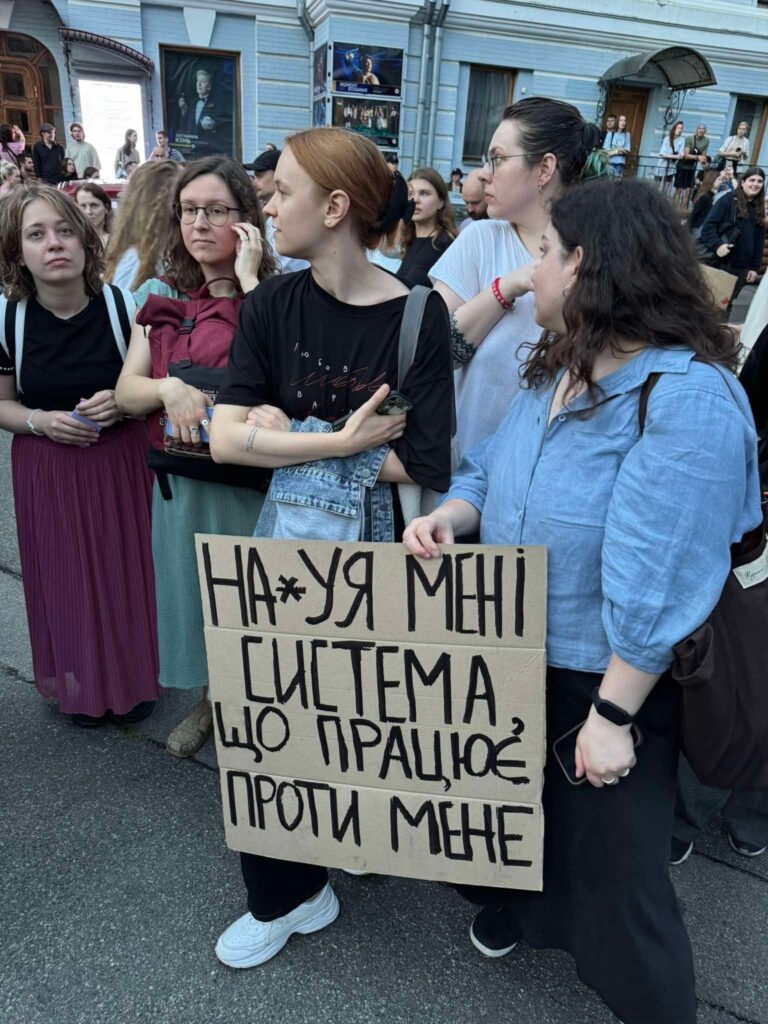

The slogan “I need a system that works for me” would be fine for intellectuals, he argued. But “Why the fuck do I need a system that works against me?” reaches ordinary people’s minds. “Because that’s exactly how they talk.”

Behind those Facebook posts scolding protesters about “pure language,” Ravchev detected real fear: “The authorities are terrified that profane protest slogans will reach mass voters and sweep them away.”

Academic Volodymyr Kulyk found himself shouting “The Office fucked up” despite never swearing in front of his wife in 35 years. The moment surprised him—but he understood what was happening.

The youth had “finally desacralized power, which can now be addressed without picking words, at least when it deserves it,” he wrote. When even a polite academic starts cursing at the government, something fundamental has shifted.

The war’s children with gray hair

But there was a deeper reason behind the raw language. These weren’t typical teenagers. Tetiana Troshchynska noted: “My hairdresser tells me about all the gray children she gives haircuts to. 12, 13, 16 years old. Half-gray heads, gray streaks, gray like salt. I tell some, not others, because they’re sad and crying. I don’t know where they’re from, what they’ve experienced, who they’ve lost.”

The Kapranov Brothers added: “Swearing is a consequence of war, exactly like ruins, minefields and trenches. Just as we’ll have to demine forests and seas from Russian mines after the war, we’ll have to demine heads from swearing. But—after the war.”

These weren’t kids who idealized the two anti-corruption agencies, NABU (National Anti-Corruption Bureau) and SAPO (Special Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office). Most protesters readily admitted both agencies had problems—corruption scandals, slow investigations, bureaucratic failures.

But they grasped something critics missed: the choice wasn’t between perfect institutions and flawed ones. It was between flawed institutions and no independent oversight at all.

“They’re trying to get rid of essentially the only anti-corruption mechanism that Ukraine has,” Marco, a 25-year-old who lived in Chicago for a decade before returning to Kyiv, explained to Euromaidan Press. “By doing that, they’re trying to integrate it into the actual government, which makes it so the people in government who are corrupt decide whether they themselves are corrupt, right? So, it’s a little counterintuitive.”

NABU and SAPO, whatever their flaws, were the first real separation of power in Ukraine—bringing it closer to a functioning democracy and further from the likes of the autocracies in Russia and Belarus.

Poetry on cardboard: When protest signs became literature

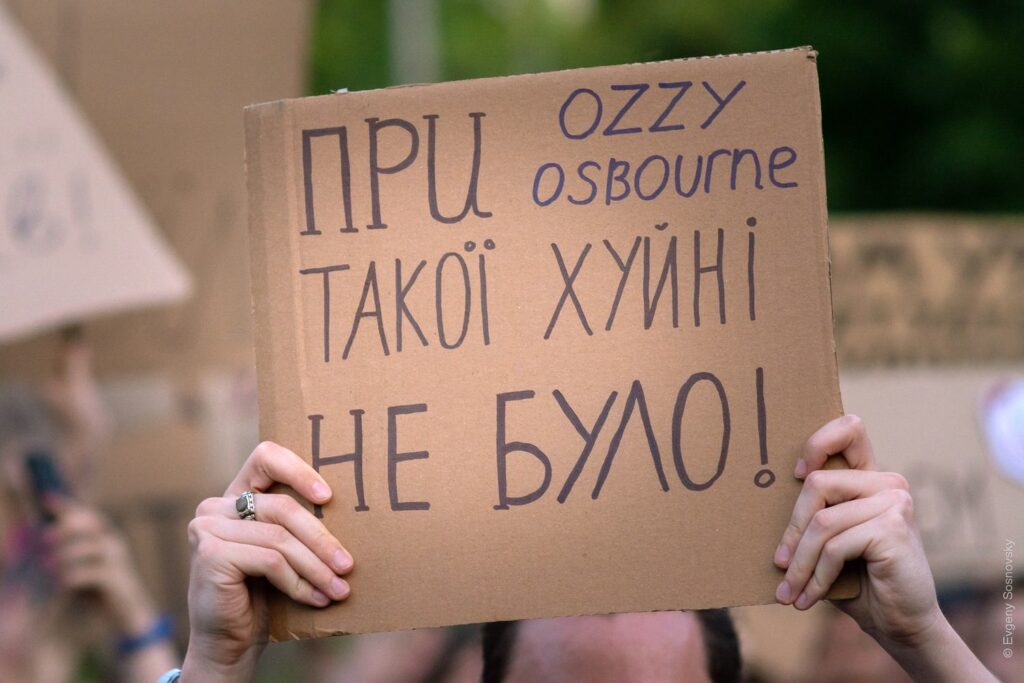

But focusing on the swearing missed the real cultural phenomenon. Most signs weren’t profane—they were poetic. Ukrainian cultural observers noted that these cardboard creations represented “real poetry, with all its nerve and broken form. Something in the tradition of Ukrainian futurists—short, with broken lines, unconventional syllable division.”

Signs mixed Latin script with Cyrillic, quoted Taras Shevchenko alongside modern poets, featured portraits of Lesya Ukrainka next to Zelensky caricatures. “Do cattle low when NABU is whole?” parodied Ukraine’s most famous poem. “Nations don’t die of heart attacks—first their NABU and SAPO are taken away,” riffed on national poet Ivan Franko.

“If you want to know where modern poetry is in Ukraine—here it is, on these cardboards,” one literary critic observed. “Poetry as a weapon is something very Ukrainian.”

This was Ukraine’s first Twitter-era protest movement, where anyone could express themselves in short, punchy statements.

Yet paradoxically, it produced some of the most sophisticated political poetry seen on Ukrainian streets:

- “Do cattle low when NABU is whole?”—parodying a 19th-century Ukrainian novel by Panás Myrnyi, which basically says that cattle (people) don’t complain when they’re well-fed

- Nations don’t die of heart attacks—first they lose their NABU and SAPO”—riffing on modern poetess Lina Kostenko, “Nations don’t die of heart attacks—first they lose their speech”

- or the blunt “Why the fuck do I need a system that works against me?”

The unspoken wartime contract, broken

“I demand 263 explanations,” says one protester, invoking the 263 MPs who voted for the law, amid a sea of Gen Z’s cardboard signs right at the backyard of the President’s Office in Kyiv. Photo: Evgeny Sosnovsky

The protests revealed something deeper than anger over specific legislation. As wounded veteran and protester Sabir explained: “We had an unspoken social contract: we don’t criticize the authorities during war, but they don’t pull any bullshit. But they kept pulling bullshit. Now they decided they could allow themselves more. People showed they couldn’t.”

The speed of the legislation shocked even seasoned political observers. Bills typically languish in parliament for months. This one passed in hours, with Zelensky signing it the same evening as protests erupted outside his office.

“When you pass such a law in one evening, it looks very much like fear of losing power,” said IT worker Olena Danyliuk, 31. “They’re trembling at the thought they might have to give up power.”

EU officials were reportedly shocked when they learned of the legislation. Brussels had planned to secretly fast-track Ukraine’s accession talks, but the anti-corruption law threatened that timeline. Perhaps Ukraine was following Georgia’s trajectory—offering high hopes but ultimately succumbing to pro-Russian authoritarianism?

Not so fast, said the youngsters with their “silly” signs.

When Gen Z rebellion goes right

The contrast with Western youth movements couldn’t be more vivid. While American and European teenagers often target democratic institutions themselves—demanding to tear down systems they see as irredeemably corrupt—Ukrainian Gen Z fight to preserve and strengthen democratic institutions against authoritarian capture.

This difference reveals an ironic truth: Western youth don’t know how good they have it. They’ve never lived without independent courts, free press, or anti-corruption agencies. They can afford to attack these institutions because they’ve never experienced their absence.

Ukrainian twenty-somethings have gray hair at 16 and dead relatives in their family trees. They know exactly what happens when democratic institutions disappear. They are, actually, dying for a stab at a democratic future, not the one that Russia offers—where opposition figures end up dead or imprisoned, where corruption flows unchecked because there’s no independent oversight.

As veteran protester Ivan Chyhyryn, who lost his leg rescuing a wounded comrade, told reporters: “My parents were on Maidan in 2014 when I was very young. Creating independent anti-corruption institutions was one of their goals. What my parents fought for is now being thrown away.”

His generation inherited revolution in their DNA—the Orange Revolution in 2004, the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, and now resistance to democratic backsliding in 2025. But unlike previous generations who had to build democracy from scratch, these youth were defending institutions they’d grown up with.

The cardboard revolution’s victory

By Wednesday evening, Zelensky announced he would submit new legislation preserving anti-corruption agencies’ independence. “We heard the street,” he said—the same president who’d ignored international criticism and parliamentary opposition.

And this illustrated the main difference between Ukraine and Russia: Russian opposition complains it can’t change anything while Ukrainian teenagers flood the streets with “Fuck corruption” signs and win.

“I genuinely believe that if this happened in Russia, police would have just come in and beat everybody up,” Marco told Euromaidan Press. “In Ukraine, though, we really are freedom-loving and we will show the government that we are the ones in charge, not them.”

Even Russian independent media called these protests a “political crisis.” For Russians, street demonstrations represent a system breakdown. For Ukrainians, they represent the system working—checks and balances moving from the streets into the political fabric.

As protester Polina put it: “Only we can fight for our best future. That’s why we’re all here.”

Not bad for a generation whose main political tools are Twitter, Telegram, and magic markers.