Sybiha tells Hungarian counterpart Ukraine ready for “mutually respectful” talks

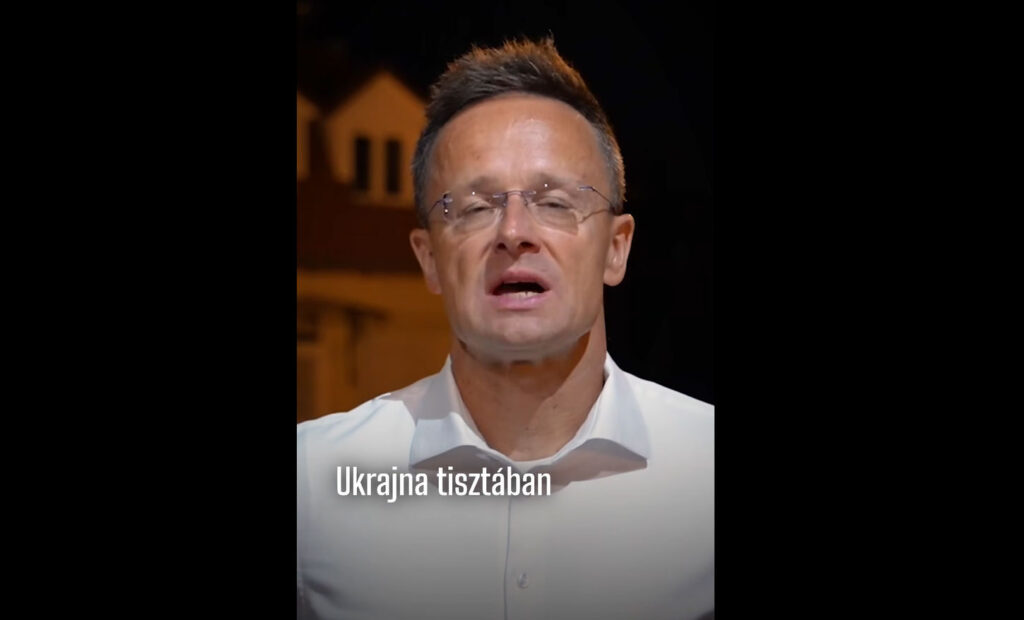

Ukrainian Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha held telephone talks with his Hungarian counterpart Péter Szijjártó on 9 September, discussing Russian escalation and Ukraine’s European integration prospects, according to Ukraine’s Foreign Ministry press service.

“During our call, I informed Péter Szijjártó about Russia’s escalation of terror and reiterated Ukraine’s commitment to peace efforts,” Sybiha said.

He emphasized that Ukraine needs “consolidated support of international community to increase pressure on Russia and advance peace process.”

The ministers addressed upcoming bilateral engagements, including Deputy Prime Minister Taras Kachka’s planned visit to Budapest and other future contacts between the two countries. Sybiha noted they would hold consultations on Hungarian national minority rights the following day.

“Ukraine is ready to work on all bilateral issues in a mutually respectful manner,” the Ukrainian foreign minister said, according to the ministry’s statement.

Sybiha pressed his Hungarian colleague on Ukraine’s EU accession timeline, underlining “the need to open negotiation clusters in Ukraine’s EU accession talks as soon as possible and secure all EU member states to support this step.”

The Ukrainian minister welcomed Hungary’s recent energy deal, praising the country’s “10-year gas supply agreement with Shell as a milestone step toward strengthening energy security for our region and all of Europe.”

The diplomatic outreach comes after recent tensions between the two foreign ministries over strikes on the Druzhba oil pipeline and Ukraine’s EU membership prospects. Following these public disagreements, Sybiha had called on his Hungarian counterpart to engage in direct dialogue rather than social media disputes.