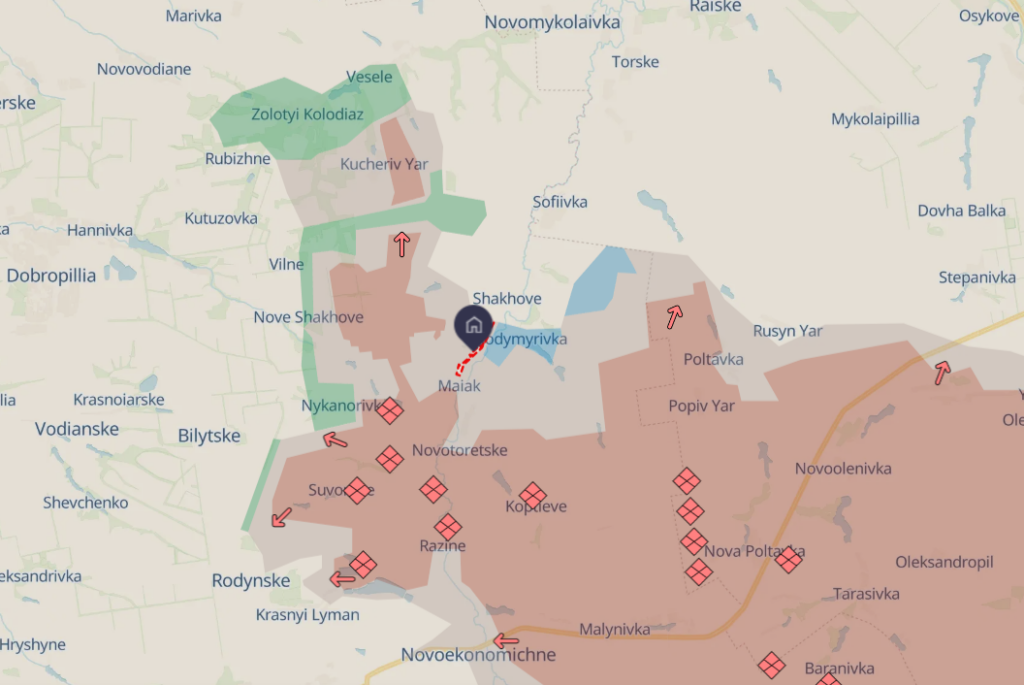

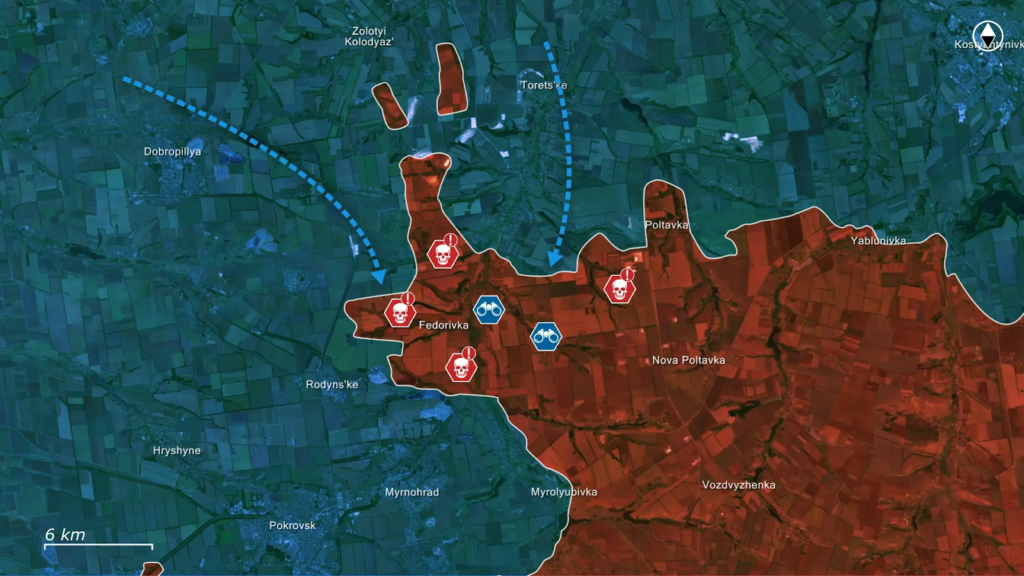

Russian forces conducted an underground infiltration mission through a gas pipeline near Kupiansk, marking the third documented use of this tactic during the war, according to a Ukrainian military intelligence (GUR)-affiliated source.

The operation began when Russian forces “entered a gas pipeline from a wooded area near Lyman Pershyi (northeast of Kupiansk), traveled through the pipe for an estimated four days with electric scooters and modified wheeled stretchers, and exited the pipe near Radkivka (immediately north of Kupiansk),” the Ukrainian source reported on 12 September, according to the ISW.

After emerging from the pipeline, Russian forces advanced toward Kupiansk and the nearby railway line, according to the intelligence source. The Ukrainian General Staff confirmed the mission occurred but stated that Russian forces “are accumulating on the northern outskirts of Kupiansk but have not entered Kupiansk itself.”

Ukrainian forces have since responded to neutralize the infiltration route. “Ukrainian forces have since struck and damaged the pipeline and Russian forces are no longer able to advance through the pipeline,” stated the commander of a Ukrainian drone regiment operating in the Kupiansk direction.

Russian military bloggers suggested uncertainty about the mission’s timing, with some claiming “Russian forces may have advanced through the gas pipeline in early September 2025, indicating that the footage may be up to a week and a half old.”

Kupiansk Military Administration Head Andriy Besedin clarified the current situation on September 13, stating that “Russian forces do not currently hold positions in Kupiansk but fighting is ongoing near the outskirts of the city.”

Pattern of tactical innovation spreads across front lines

This marks the third documented use of pipeline infiltration tactics by Russian forces. Previous operations occurred in Avdiivka, Donetsk Oblast in January 2024 and in Sudzha, Kursk Oblast in March 2025, with elements of the Russian 60th Veterany Separate Assault Brigade participating in both earlier missions.

The Institute for the Study of War (ISW) reported that the spread of this tactic indicates improved knowledge transfer within Russian military command. ISW has not observed reports of the 60th Veterany Brigade operating in the Kupiansk direction, “indicating that the Russian military command is disseminating the brigade’s knowledge and success in such missions to other units and formations.”

ISW previously noted in January 2025 that “the Russian military command appeared to be at least attempting to improve its ability to disseminate lessons learned, given that Russian forces are exhibiting similar operational patterns across the front line.”

The tactic may also reflect individual unit adaptation to Ukrainian drone capabilities, as pipelines “provide Russian forces with natural cover and concealment that can enable forward movement,” according to ISW analysis.

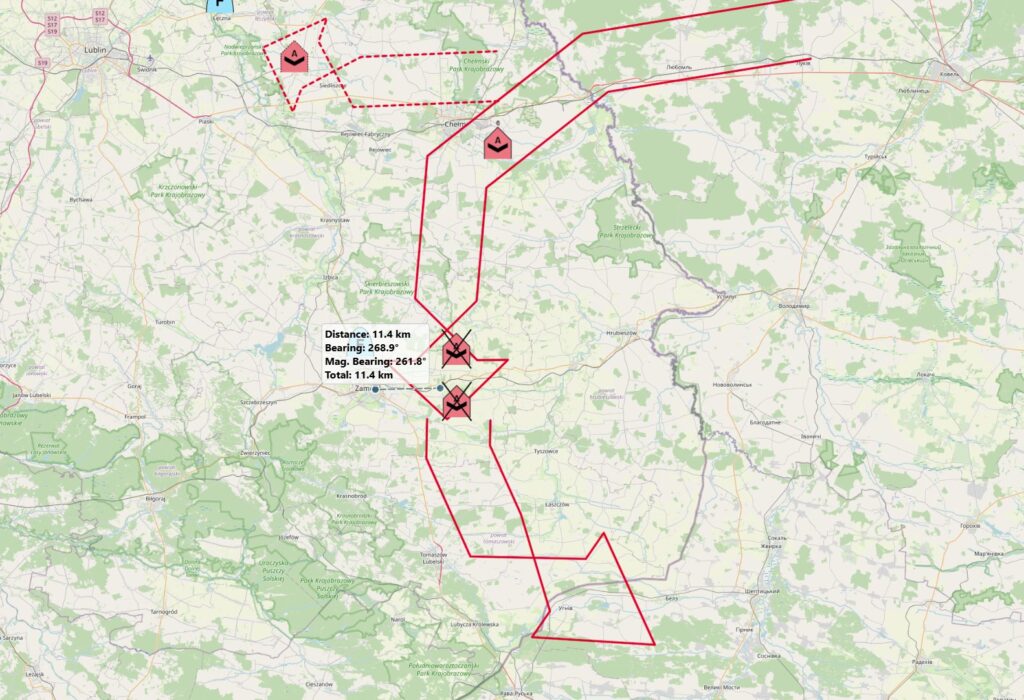

International condemnation grows over Polish airspace violation

The international community has intensified criticism of Russia’s recent drone incursion into Poland. Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Marcin Bosacki presented a joint statement at the United Nations on 12 September, in which nearly 50 countries condemned Russia’s violation of Polish airspace on 9-10 September with 19 drones.

“Russia purposely violated Poland’s territorial integrity and trespassed against NATO and the EU,” Bosacki stated at the UN.

Ukrainian Permanent Representative to the UN Andriy Melnyk characterized the incident as deliberate provocation, stating that Ukraine shares Poland’s view that “the Russian drone incursion was not a technical error, but rather a deliberate act aimed at escalating tensions and testing the international community’s response to ongoing Russian aggression.”

US Acting Permanent Representative Dorothy Shea reinforced NATO commitments, reiterating that the United States remains committed to defending “every inch of NATO.” Shea linked the airspace violation to broader Russian escalation, noting that “Russia has intensified its air campaign against Ukraine following the US-Russia Alaska Summit on August 15” and that such actions demonstrate “immense disrespect for good faith US efforts” to usher in peace.

Russian and Belarusian denials contradicted by evidence

Russian and Belarusian officials have attempted to deflect responsibility for the airspace violation. Russian UN Representative Vasily Nebenzya claimed Poland “hastened to place the blame on Russia without presenting any evidence linking Russia to the incident.”

Nebenzya argued the drones could not be Russian because “the range of the drones found in Poland does not exceed 700 kilometers.” The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs claimed Russia “refuted the speculations… about plans to attack one of the NATO countries.”

Belarusian UN representative Artem Tozik dismissed Poland’s accusations as “baseless” and claimed Belarus “was the first to inform Poland about the approach of drones that ‘went off course’ during the overnight Russian strikes against Ukraine.”

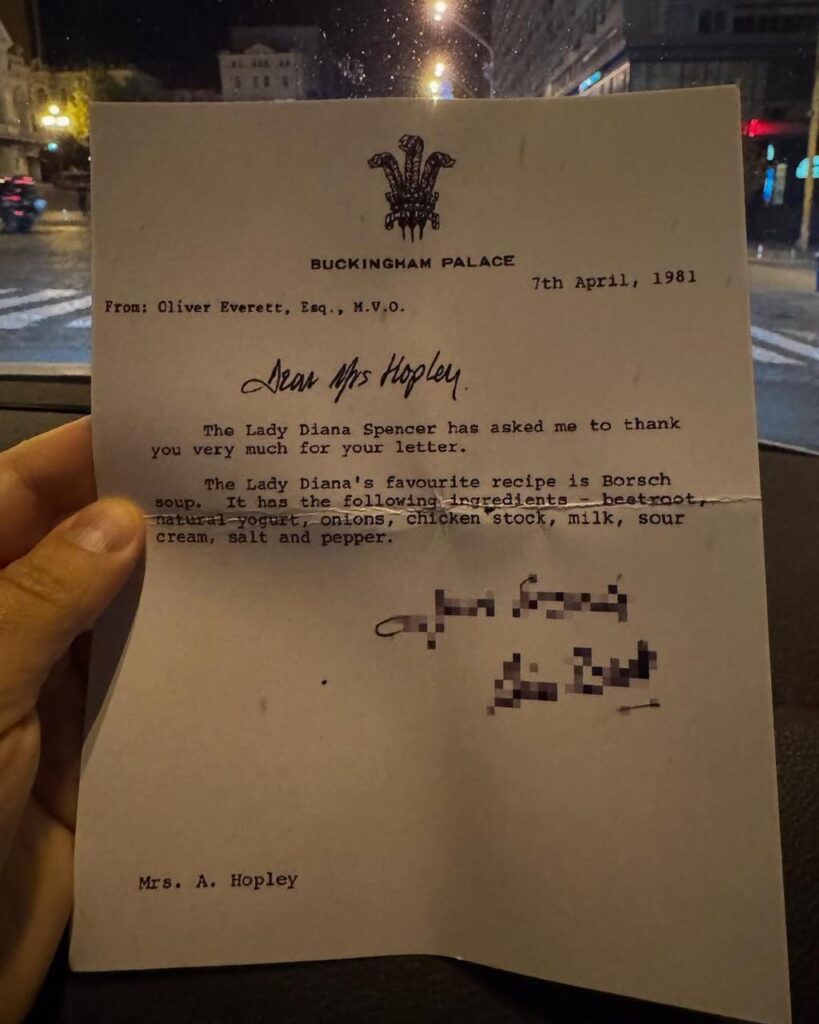

However, physical evidence undermines these denials. Sky News published images of Russian Gerbera drones that landed in Poland, while Bosacki shared images showing Cyrillic letters on the drones at the UN Security Council meeting.

Ukrainian outlet Militarnyi’s analysis of Sky News images revealed the drone was equipped with “an Iranian-made Tallysman satellite navigation four-channel controlled reception pattern antenna (CRPA).” These devices “filter out false signal sources from electronic warfare systems in order to make the drone more resistant to EW,” making it “unlikely that these Russian drones flew off course due to EW jamming.”

The scale of the September 9-10 incursion involving at least 19 drones “is roughly three times the number of projectiles that have breached Polish airspace during the entirety of Russia’s full-scale invasion.” ISW assessment indicates it is “extremely unlikely that such a concentrated number of drones could have violated Polish airspace accidentally or due to technical or operator error.”

Additional evidence includes fuel tanks that extended drone range “as far as 900 kilometers,” contradicting Nebenzya’s range-based denial, according to ISW analysis.