Russia’s 137× drone surge wasn’t magic—it was Chinese engines labeled “fridges”

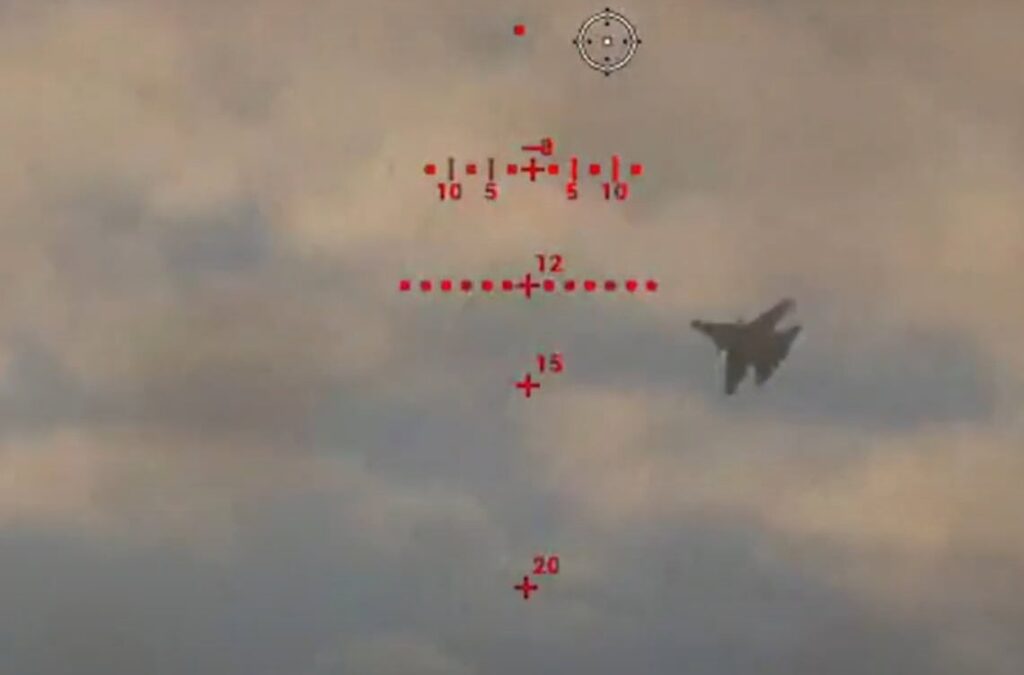

Your smartphone probably has more computing power than the drone that woke Ukrainian families at 3 AM this morning. Yet these cheap weapons have become Putin’s most reliable tool for terrorizing Ukraine—and they’re multiplying faster than anyone expected.

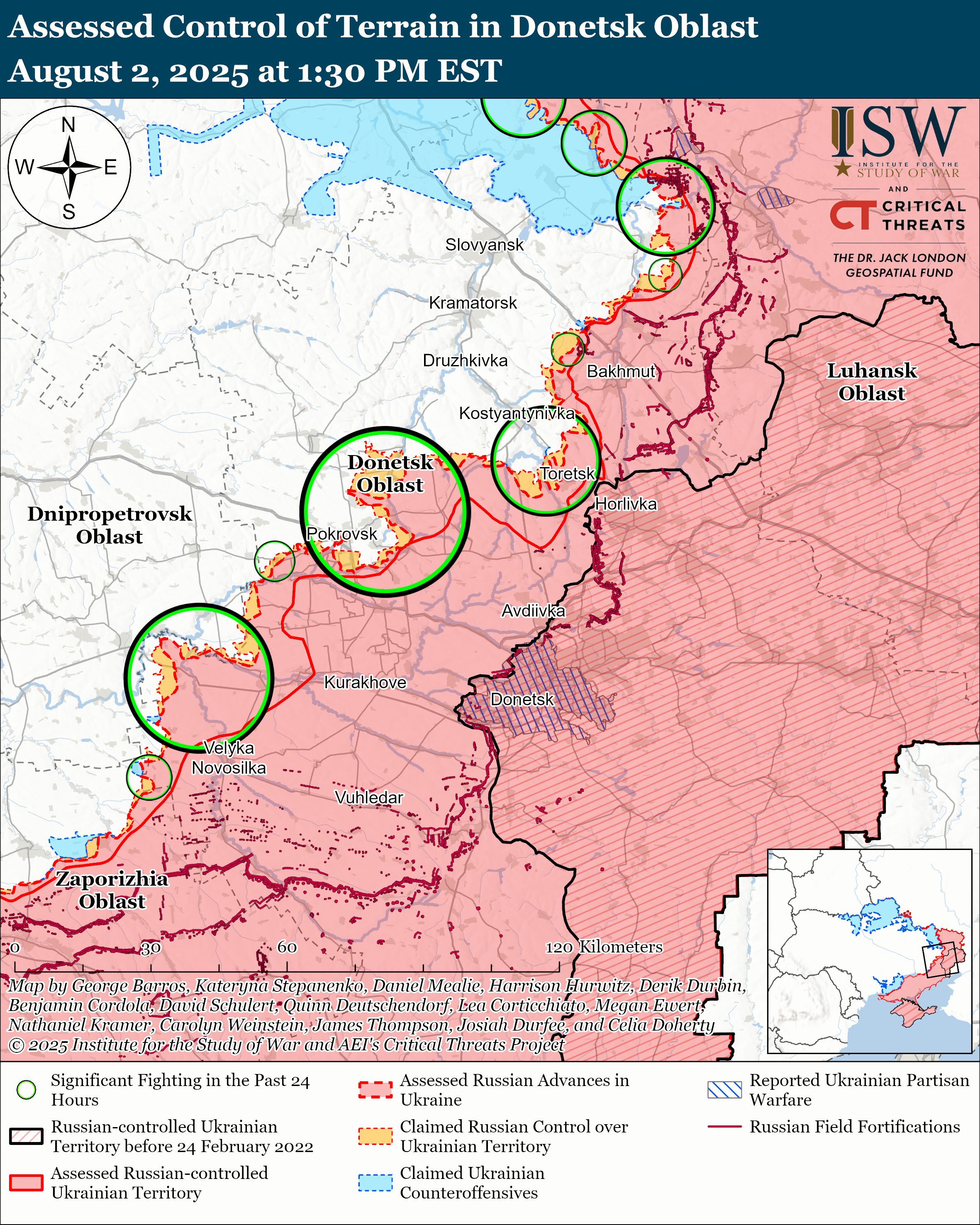

Russia launched more than 728 drones in a single night attack on 9 July 2025. In June alone, 5,483 drones targeted Ukraine—16 times more than June 2024 and a 30% increase over the previous month. Compare that to September 2022, when Russia’s entire monthly arsenal was just 40 units.

According to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Russia has launched 28,743 drones at Ukraine since February 2022. The escalation has been systematic: 40 drones in September 2022, increasing to 5,483 by June 2025—a 137-fold increase over 33 months.

What changed?

A German aviation engine from the 1980s, now manufactured in China and smuggled to Russia.

The Shahed transformation

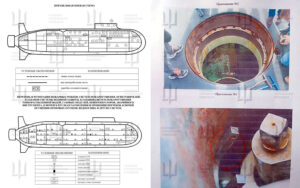

The Shahed-136 represents a shift in modern warfare—establishing what defense analysts call asymmetric warfare through large-scale, low-cost swarm attacks. Iran’s HESA reverse-engineered a 1980s German design (the Die Drohne Antiradar) to create a flying bomb that carries 118 pounds (53 kg) of explosives over 1,000 miles (1,600 km).

Iran initially sent combat drones to Russia on 19 August 2022—both Mohajer-6 surveillance drones (200km range, two missiles per wing) and Shahed kamikaze units. Tehran and Moscow officially denied the transfers, but Iran later acknowledged them while claiming they predated the invasion.

In early September 2022, IRGC Commander Major General Hussein Salami noted that Iran was selling domestic military equipment to foreign buyers, including “major world powers,” and training them to use this equipment.

But the real game-changer came with Iran’s $1.75 billion technology transfer deal that gave Russia the blueprints, software, and production technologies to build its own versions. Shahed drones were previously built by Shahed Aviation Industries in Iran, where allegedly every drone factory has two backup sites in case of aerial attacks.

Inside the Alabuga factory boom

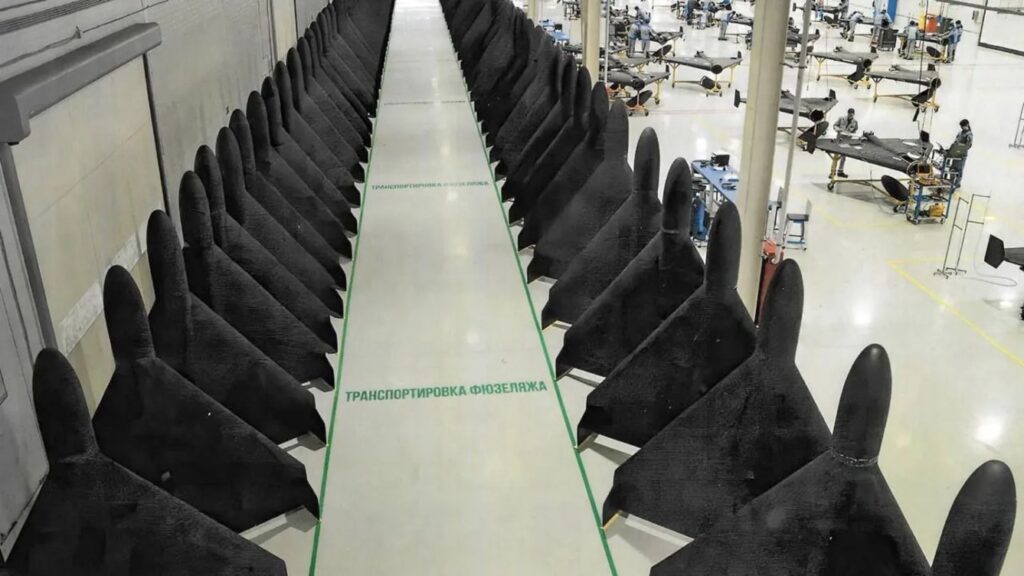

Russia’s drone production centers on the Alabuga Special Economic Zone in Tatarstan—more than 1,300 kilometers from Ukraine’s border and Russia’s most successful SEZ, accounting for 68% of total revenue. The facility produced 2,738 Shahed-style drones in 2023, then more than doubled to 5,760 units by September 2024.

Recent analysis suggests Russia produced over 10,000 drones in 2024 alone, doubling monthly production from 1,000 to nearly 2,000 units.

The original contract called for 6,000 drones by September 2025—a target the facility appears to have exceeded well ahead of schedule.

Satellite imagery shows at least eight new warehouse structures under construction. The Institute for Science and International Security estimates Alabuga now produces almost 20 drones per working day—double the original contract rate. Russia initially predicted production costs of $48,000 per Geran-2 (25% of the purchase cost), but by April 2024 this increased to around $80,000 due to upgrades. The original plan called for 310 drones per month with 24-hour operations, plus plans for an additional 6,000 drones per year after the initial contract.

The main structural components requiring sophisticated supply chains are the airframe (fuselage), engine, avionics (electronics), and combat unit.

Russia started with a three-phase plan:

Phase 1 was reassembling 100 drones per month from Iranian knock-down kits.

Phase 2 would produce their own airframes.

Phase 3 would produce another 4,000 drones by September 2025 with little Iranian help.

Alabuga Machinery LLC completed construction of production buildings in December 2022 and sent its first team of specialists to Iran for training in March 2023. In parallel, the process of assembling drones from Iranian machine kits continued.

But there were problems. About 25% of Iranian kits arrived damaged or broken—including one dropped during delivery.

Here’s the interesting part: leaked data shows 90% of Iranian Shahed-136’s computer chips and electrical components are manufactured in the West, primarily in the United States.

So even “Iranian” drones are mostly Western technology.

Iran initially helped Russia with direct connections. According to the US Treasury Department, Alabuga requested meetings with Mado Company officials (Iranian drone engine producers) and received detailed documents on the MD550 engine that powers the Shahed-136. Iran’s Defense Ministry also facilitated the supply of UAV parts, models, and ground stations to Alabuga through UAE-based Generation Trading FZE.

What makes this surge possible? A Chinese supply network that signed contracts worth 700 million yuan ($96 million) with Alabuga between September 2023 and June 2024. Thirty-four Chinese companies partnered with the facility during this period.

The Chinese engine pipeline

Here’s where it gets interesting. The heart of Russia’s drone program is a Limbach L550E engine—originally designed by German company Limbach Flugmotoren in the 1980s. Iran reverse-engineered this decades ago. Now, Chinese company Xiamen Limbach Aircraft Engine Co. manufactures these engines and ships them to Russian weapons factories.

Xiamen Limbach is wholly owned by Fujian Delong Aviation Technology Co., which also owns the original German Limbach Flugmotoren GmbH—one of the world’s leading manufacturers of aircraft piston engines engaged in both development and maintenance. The engines don’t go directly to Russia—they flow through intermediary companies that act as buffers between IEMZ Kupol and Chinese suppliers.

Between November 2023 and October 2024, Russian intermediary TSK Vektor LLC imported $32.8 million worth of components from Chinese suppliers: aircraft engines, computer parts, electrical equipment, transistors, electronic modules, connectors, plugs, sockets, spare parts, and components.

The broader Chinese supplier network with specific roles includes:

- Xiamen Limbach Aircraft Engine Co.: L550E engines through intermediaries (Redlepus TSK Vektor Industrial, Shenzhen Juhang Aviation Technology)

- Redlepus Vector Industry (Shenzhen): Avionics, electronic modules, mechanical components

- Shenzhen Juhang Aviation Technology Co.: Aviation components, axles, carburetors, engine parts ($36.3 million imported 2022-2023)

- Mile Haw Xiang Technology Co.: UAV engine development, production, marketing; DLE60 engines for Gerbera drones

- Skywalker Technology: Gerbera drone fuselages and components through third-party suppliers

- Souzhou Ecod Precision Manufacturing Co.: Precision components for drone assembly

- Shenzhen Jinduobang Technology Co.: Electronic and mechanical components

- Suzhou Shunxinge Import and Export Trade Co.: Import/export facilitation

- Shandong Xinyilu International Trade Co.: Electronic components and trade facilitation

- Fujian Jingke Technology Co.: Technical components and systems integration

Most label exports as “for general civil purpose” or “for general industrial purpose” to avoid detection.

When Reuters reported the Chinese engine connection in September 2024, the US and EU sanctioned several companies, including Xiamen Limbach. The EU also suspects Xiamen Limbach may have passed L550 engine drawings directly to Iranian Shahed-136 manufacturers.

But Beijing Xichao International Technology and Trade immediately took over L550E shipments.

The engines now travel from Beijing to Moscow to Izhevsk, labeled as “industrial refrigeration units.”

Engines are shipped to Russian front company SMP-138 (registered under Abram Goldman), then forwarded to LIBSS. The contract explicitly states engines will be described as cooling units because of their sensitivity.

Russia’s drone variants

Russia hasn’t just copied Iran’s design. The Garpiya-A1 (“Harpy”), manufactured by IEMZ Kupol (part of Almaz-Antey), closely resembles the Shahed-136 but uses Chinese L550E engines and unique bolt-on fins. Russia’s Defense Ministry signed a 1 billion ruble contract ($10.9 million) with IEMZ Kupol in early 2023 to develop the drone factory.

Between July 2023 and July 2024, Russia produced more than 2,500 Garpiya-A1 UAVs. IEMZ Kupol signed a contract to produce more than 6,000 Garpiya drones in 2025, up from 2,000 in 2024, with more than 1,500 delivered by April 2025. Ukrainian intelligence reports about 500 Garpiya drones are launched monthly.

Russia has shifted from using Iranian “M” series Shaheds to producing its own “K” and “KB” variants since 2023, indicating full domestic production capability. Conflict Armament Research, a British weapons-tracking group, examined downed drones and confirmed Russia is now producing its “own domestic version of the Shahed-136.”

But Russia’s cleverest innovation is the Gerbera drone—a foam and plywood decoy that costs one-tenth the price of a real Shahed but appears identical on radar. It forces Ukrainian air defenses to waste expensive interceptor missiles on worthless targets while real attack drones slip through. Russia planned to produce 10,000 Gerberas in 2024—twice the number of actual attack drones.

Russia also produces the Geran-3, a jet-powered variant with higher speeds for faster targeting and better evasion of antiaircraft systems.

The exploitation workforce

How does Alabuga staff this massive operation? Through questionable recruitment that raises human rights red flags.

They planned for 810 staff working in three shifts to run the facility 24/7. The facility employs over 1,000 women from across Africa, recruited through Alabuga Start with promises of $550 monthly salaries, subsidized housing, and educational opportunities. The recruitment campaign in Uganda’s capital, Kampala, specifically targeted young female students. Management seizes passports to prevent workers from quitting—basically forced labor.

The factory also employs Russian students as young as 15 through local polytechnic colleges, including Alabuga Polytech. As of August 2023, several hundred 15‑year‑old students worked at Alabuga Polytech under “work experience programs,” with employers promising wages up to 70,000 rubles/month (around US $700)— roughly 20–30 % higher than typical monthly earnings in Tatarstan.

The Shahed builders were disturbed about building weapons for the war against Ukraine, so Alabuga keeps hiking salaries. Some workers now earn ten times the median Russian wage.

US Treasury sanctions specifically cited Alabuga CEO Timur Shagivaleyev for “exploitation of underage students to assemble these UAVs.”

How they evade sanctions

How does Russia pay for Chinese technology? Russia built a network that avoids the banking system and instead pays with gold bars, commodities, and barter deals.

Iran’s pricing changed through negotiations. Initially, Iran wanted approximately $375,000 per drone. Final deals settled at either $193,000 per unit for orders of 6,000 drones or $290,000 for orders of 2,000 units.

In February 2023, Alabuga Machinery allegedly transferred 2,067,795 grams of gold bars to Iranian proxy company Sahara Thunder as payment for components—more than 2 tons of gold signed off by CEO Shagivaleyev.

Sahara Thunder was later sanctioned by OFAC in April 2024 for supporting Iran’s Defense Ministry and facilitating UAV transfers. The company was identified as a front for Iran’s military, also shipping commodities to China and Venezuela.

The total contract value reached $1.75 billion through gold transfers, barter arrangements, and commodity swaps designed to circumvent Western sanctions.

The sanctions whack-a-mole problem

Chinese component supply shows the real problems with current sanctions. Despite China’s export control law supposedly preventing dual-use technology transfers, there are obvious gaps in prohibited classification codes that allow systematic workarounds. Export control measures don’t match actual dual-use risks, so Russian manufacturers keep getting critical technologies despite formal bans.

When the US and EU sanctioned Xiamen Limbach in October 2024, Beijing Xichao International Technology took over shipments within weeks. This rapid substitution suggests pre-existing networks designed to maintain supply continuity.

Chinese suppliers have developed sophisticated systems to disguise military components. According to European security officials, engines are shipped as “industrial refrigeration units,” electronic components as “general civil purpose” items, aircraft parts as “general industrial equipment.” This “cooling units” description enabled goods to be exported without alerting Chinese authorities.

Sanctioned entities include:

- Xiamen Limbach Aircraft Engine Co.: Sanctioned October 2024 for engine supply

- Redlepus TSK Vektor Industrial: Sanctioned for facilitating component transfers

- TSK Vektor LLC: Russian intermediary sanctioned for procurement activities

- IEMZ Kupol: Sanctioned December 2022 (EU), December 2023 (US)

- Sahara Thunder: Iranian company sanctioned April 2024 for supporting Iran’s Defense Ministry

- Timur Shagivaleyev: Sanctioned for exploitation of minors

But when one Chinese company gets blacklisted, another replaces it within weeks.

Secondary sanctions targeting third-party companies have proven insufficient. Chinese companies face limited consequences for supplying Russian defense contractors, and new entities can be established faster than sanctions regimes can identify them.

What this means for the West

This collaboration shows how authoritarian states can create integrated defense partnerships that bypass Western sanctions. The partnership has built covert payment networks involving gold transfers and middleman countries that make enforcement harder.

A new Deng Xiaoping Logistics Complex being built near Alabuga will handle 100,000 containers annually via direct rail links between Russia and China, suggesting broader military cooperation.

The psychological impact goes beyond military effectiveness. These weapons target civilian infrastructure—power plants, hospitals, schools, apartments—designed to wear down Ukrainian society through constant air raids. Ukrainian families spend nightly hours in bomb shelters, kids sleeping in bathtubs to avoid strikes.

The weapons strain Ukrainian air defenses in critical ways. Ukraine intercepts most drones, but the cost equation favors attackers: a $500,000 interceptor missile destroys a $50,000 drone. If attacks continue at current intensity, this creates unsustainable resource imbalances that could overwhelm air defense systems through economic attrition rather than penetration.

If Russia can produce 10,000+ attack drones annually using Chinese components and Iranian designs, similar capabilities could threaten NATO members.

The weapons represent cost-effective methods for sustained attacks against civilian infrastructure across Europe, potentially overwhelming air defense systems through sheer volume.

European officials have urged China to tighten export controls, with EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas warning Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi that Chinese firms’ support threatens European security. Beijing denies knowledge of military applications while maintaining its right to trade with Russia under international law.

The policy challenge

Current sanctions haven’t worked to stop this supply chain. China has become the key enabler—Ukrainian intelligence reports that every critical component (engines, navigation systems, control units) comes from Chinese manufacturers.

What needs to change:

Better coordination: Allies need to align sanctions policies targeting both Russian UAV manufacturers and Chinese suppliers. Right now, sanctions are scattered and don’t deter anyone.

Hit Chinese companies harder: Aggressive secondary sanctions against Chinese manufacturers and their parent companies who help transfer technology to Russia. This includes targeting banks that enable these deals.

Close export loopholes: Tighten control over dual-use technology exports from China, close gaps in prohibited classification codes that currently allow systematic workarounds. Better coordination between customs and intelligence agencies to catch evasion attempts.

Pressure Beijing financially: Enhanced diplomatic pressure on Beijing to stop Chinese firms from transferring critical technologies that enable weapons production. This includes targeting gold-based payment networks and commodity swap deals.

Share intelligence better: Better intelligence coordination between allies to track emerging supply chains and identify new middleman companies before they get established.

The drone attacks hitting Ukraine carry Chinese engines, Iranian designs, and Russian assembly. They’re a test case for whether economic isolation can work in a connected global economy. So far, determined state actors with willing partners can get around almost any restriction.

Whether Western governments can adapt their systems to match evasion network sophistication is still an open question. The answer will decide not just Ukraine’s fate, but whether economic tools can actually deter international aggression.