Israeli Settler Attack During West Bank Olive Harvest Leads to Death of a Boy

© Afif Amireh for The New York Times

© Afif Amireh for The New York Times

A Ukrainian court sentenced a Russian soldier to life in prison on 6 November for executing a surrendered Ukrainian prisoner of war—the first such ruling in Ukraine's history. The verdict exposes a pattern documented throughout 2025: Russia systematically tortures, kills, and conceals Ukrainian POWs from monitors, while international bodies report Ukraine provides Russian captives with medical care and unrestricted UN access.

Dmitry Kurashov, 27, shot 41-year-old veteran Vitalii Hodniuk at point-blank range in January 2024 after Hodniuk ran out of ammunition and laid down his arms, according to Ukraine's Security Service (SBU). Ukrainian forces captured Kurashov later that same day. He had been recruited from a Russian prison to serve in a "Storm-V" assault unit, Suspilne reported.

The Zaporizhzhia court conviction arrives as three major international investigations—by the OSCE, Amnesty International, and the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission—published findings throughout 2025 documenting systematic Russian violations of international humanitarian law.

The reports describe a deliberate policy architecture: torture as routine practice, enforced disappearances to prevent accountability, manipulation of international monitors, and denial that captured Ukrainians qualify as prisoners of war at all.

The contrast with Ukraine's treatment of Russian prisoners could hardly be sharper. While Russia conceals captives and blocks monitor access, Ukraine maintains established internment facilities with full UN oversight.

Kurashov's execution of Vitalii Hodniuk is far from an isolated case. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported another case: 33-year-old Ukrainian National Guard soldier Vladyslav Nahornyi, captured near Pokrovsk in August 2025. Russian forces took him and seven other Ukrainian soldiers to a basement, hands tied behind their backs.

From his hospital bed, unable to speak after Russian forces slit his throat, Nahornyi described in written notes what happened next. The reconnaissance soldiers captured first had their eyes gouged out, lips cut off, ears and noses removed, male organs mutilated. Then Russians cut all their throats and threw them into a pit. Nahornyi was the only survivor. Using a broken glass bottle, he cut his bindings, bandaged his throat, and crawled for five days to Ukrainian positions.

His survival suggests many more Ukrainian soldiers may have been killed or tortured to death immediately after capture. Not officially recognized as prisoners of war, they never stood a chance at survival. The case exemplifies the summary violence toward Ukrainians that has become standard practice by Russian forces.

Amnesty International's March 2025 report "A Deafening Silence" documented torture methods used systematically across Russian detention facilities. Researchers interviewed dozens of former Ukrainian POWs and civilian prisoners who described remarkably consistent patterns: immediate torture upon capture, electric shocks, beatings severe enough to cause death, denial of medical care, and prolonged isolation designed to break prisoners psychologically.

Russian authorities use torture not primarily for interrogation but as punishment and intimidation. Many prisoners described being tortured even after providing all requested information. The goal appears to be inflicting maximum suffering rather than extracting intelligence.

Enforced disappearance emerged as another systematic practice. Russia refuses to acknowledge holding many Ukrainian prisoners, making it impossible for families to locate them or for international monitors to verify their treatment. Some prisoners remain "disappeared" for months before Russia acknowledges their captivity—if it ever does.

An OSCE expert mission presented findings on 25 September revealing how Russian authorities stage-manage International Committee of the Red Cross visits. Moscow allows access only to select prisoners in relatively good condition while concealing others entirely, creating a false impression of compliance with Geneva Convention requirements for neutral monitoring.

The OSCE mission documented that Russian forces refuse to recognize captured Ukrainian military personnel as POWs at all, instead designating them as "persons detained for countering the special military operation." The same designation is used for detained Ukrainian civilians. Hence Russia treats them in criminal courts as "terrorists."

This classification, though completely fictitious and nonsensical, strips them of Geneva Convention protections and provides Russia with a legal pretext for abuse that would otherwise be clearly prohibited under international humanitarian law.

The report found that Russia routinely subjects Ukrainian military personnel to torture and summary executions, and maintains a system designed to prevent accountability. These policies may constitute war crimes and crimes against humanity under international law.

The UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission operates with "unfettered access" to Russian POWs held in established Ukrainian internment facilities. International monitors can visit any facility, interview any prisoner, and verify conditions without restriction—the standard required under the Geneva Conventions but systematically violated by Russia.

A March 2025 investigation by ZMINA.info examined why Amnesty International's major report on POW treatment focused exclusively on Russian violations. The answer was straightforward: Amnesty International Ukraine's separate study found Russian POWs in good physical condition receiving appropriate medical treatment. There was no pattern of systematic abuse to document.

Read also:

Ukraine documents 190,000 war crimes — and believes they prove Russia's plan to erase the nation

Nigeria has responded with bewilderment and alarm to Donald Trump's repeated threats to unleash American troops to, in the U.S. president’s words, protect “our CHERISHED Christians.” Speaking in Berlin on November 4, the Nigerian foreign minister Yusuf Tuggar pointedly said “what we are trying to make the world understand is that we should not create another Sudan.” Trump had earlier warned the Nigerian government that the U.S. was prepared to “go into that now disgraced country, 'guns-a blazing', to completely wipe out the Islamic Terrorists who are committing these horrible atrocities.”

Tuggar’s mention of Sudan was a reminder of what religious war and genocide looks like and how little the international community has done to stop it. He cited Nigeria’s “constitutional commitment to religious freedom” and its status as Africa’s largest democracy as reasons why it was “impossible” that the government would look away from the kind of violence Trump described. Trump did not cite any statistics when he told reporters on Air Force One that “record numbers of Christians” are being killed in Nigeria. A multifaith country, Nigeria has the sixth largest Christian population in the world. Numbers from the Pew Center show that about 93 million Christians live in Nigeria, compared to 120 million Muslims.

The U.S. president seems to be taking his lead from Texas senator Ted Cruz. The latter posted on X last month that “officials in Nigeria are ignoring and even facilitating the mass murder of Christians by Islamist jihadists.” In his ‘Nigeria Religious Freedom Accountability Act,’ Cruz said 52,000 Christians have been killed in the country since 2009 and over 20,000 churches and religious institutions have been destroyed. These numbers have been described by the Nigerian government as “absolutely absurd” and “not supported by any facts whatsoever.” Cruz called for sanctions on Nigerians officials. In his bill Cruz also called for Nigeria to be designated a “Country of Particular Concern,” a designation reserved for states that tolerate “egregious religious freedom violations.” And on Monday the Trump administration did exactly that, arguing that the designation was necessary because Nigerians were being prevented from freely expressing their beliefs.

But speak to people in Nigeria and you will get a different analysis depending on whom you ask. The violence, perpetrated by Islamist groups like Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP), and others is indiscriminate, claiming the lives of both Christians and Muslims. Tens of thousands of people have died and millions have been displaced as a result of the security situation in Nigeria. Many of these are residents in northern Nigeria, especially in the northeast and northwest, where the population is primarily Muslim.

In north-central Nigeria however, it is true that Christian communities have been targeted. Their demands for government action to stop the killings have fallen on deaf ears. I live for some of the year in Kwara State, a state in north-central Nigeria. In October, a distant relative was kidnapped with his entire family. My friends, family members and I have had to move house on short notice due to vicious attacks and kidnappings near where we live. But it’s hard to argue that Christians are being singled out when so many Nigerians of every background are dying.

“The irony is rich enough to choke on,” writes Elnathan John, a Nigerian novelist. “Trump’s America, where school boards ban books and churches preach ethnic purity, has appointed itself the saviour of our pluralism… One imagines a global exchange programme: our clerics and their preachers meeting to compare notes on how to weaponise God most efficiently.” Nigerians, broadly, acknowledge the insecurity in the country, and frequently debate the role of religion in the widespread violence. But everyone agrees that Trump’s motives are suspect. Before this recent outburst, Trump’s reputation in Nigeria, while mixed, consisted of support from a strong Christian base. The threat of military action over an internal issue has sparked widespread indignation and accusations of neocolonial overreach.

Subscribe to our Coda Currents newsletter

Weekly insights from our global newsroom. Our flagship newsletter connects the dots between viral disinformation, systemic inequity, and the abuse of technology and power. We help you see how local crises are shaped by global forces.

Trump’s Africa strategy is a decisive pivot away from traditional development aid and democratic institution-building toward hard-nosed commercial diplomacy, centered on U.S. access to critical minerals and African compliance on accepting deportees in exchange for financial incentives or favorable trade terms. Nigeria, notably, is one of the countries that has refused to take in deportees and was recently hit with 15% “reciprocal” tariffs. Ghana, which was also hit with 15% tariffs, just accepted 14 West African deportees.

Trump’s other approach to Africa has been to interfere in highly charged internal politics based on narratives that appeal to his base. This summer, Trump accused the South African government of enabling a “genocide” of white farmers, a highly politicized and disputed claim rooted in white nationalist rhetoric. While Trump said he would give special dispensation for white Afrikaner refugees from South Africa (tellingly, very few have actually taken advantage of his offer), he did not threaten violence on a sovereign country for its internal troubles as he has against Nigeria.

While Vladimir Putin has stayed quiet over the issue, Andrey Maslov, head of the Center for African Studies at Moscow’s Higher School of Economics said Trump is deliberately leading the U.S. down a path of isolation and focusing on the country’s internal problems. “He works for his core electorate and the future electorate of [Vice President] J.D. Vance, specifically its religious segment,” Maslov told Russia’s state-controlled media RT.

Does Trump’s foreign policy continue to help China position itself as the more reliable global partner? Expressing support for the Nigerian government, a Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson said Beijing “opposes any country using religion or human rights as a pretext to interfere in other countries' internal affairs.” China has invested billions in Nigerian infrastructure and minerals in recent years, and the value of its trade with Nigeria now outstrips that of the U.S. Has the global pattern been set – China now offers the carrot, while the U.S. wields the stick?

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Do Nigeria’s Christians need a savior? appeared first on Coda Story.

AI is replacing humans in the workplace, with tech companies among the quickest to simply innovate people out of the job market altogether. Amazon announced plans to lay off up to 30,000 people. The company hasn’t commented publicly on why, but Amazon’s CEO Andy Jassy has talked about how AI will eventually replace many of his white-collar employees. And it’s likely the money saved will be used to — you guessed it — build out more AI infrastructure.

This is just the beginning. “Innovation related to artificial intelligence could displace 6-7% of the US workforce if AI is widely adopted,” says a recent Goldman Sachs report.

In the last week, over 53,000 people signed a statement calling for “a prohibition on the development of superintelligence.” A wide coalition of notable figures, from Nobel-winning scientists to senior politicians, writers, British royals, and radio shockjocks agreed that AI companies are racing to build superintelligence with little regard for concerns that include “human economic obsolescence and disempowerment.”

The petition against superintelligence development could be the beginning of organized political resistance to AI's unchecked advance. The signatories span continents and ideologies, suggesting a rare consensus emerging around the need for democratic oversight of AI development. The question is: can it organize quickly enough to influence policy before the key decisions are made in Silicon Valley boardrooms and government backrooms?

But it’s not just jobs we could lose. The petition talks about the “losses of freedom, civil liberties, dignity… and even potential human extinction.” It reflects a deeper unease about the quasi-religious zeal of AI evangelists who view superintelligence not as a choice to be democratically decided, but as an inevitable evolution the tech bros alone can shepherd.

Coda explored this messianic ideology at length in "Captured," a six-part investigative series available as a podcast on Audible and as a series of articles on our website, in which we dove deep into the future envisioned by the tech elite for the rest of us.

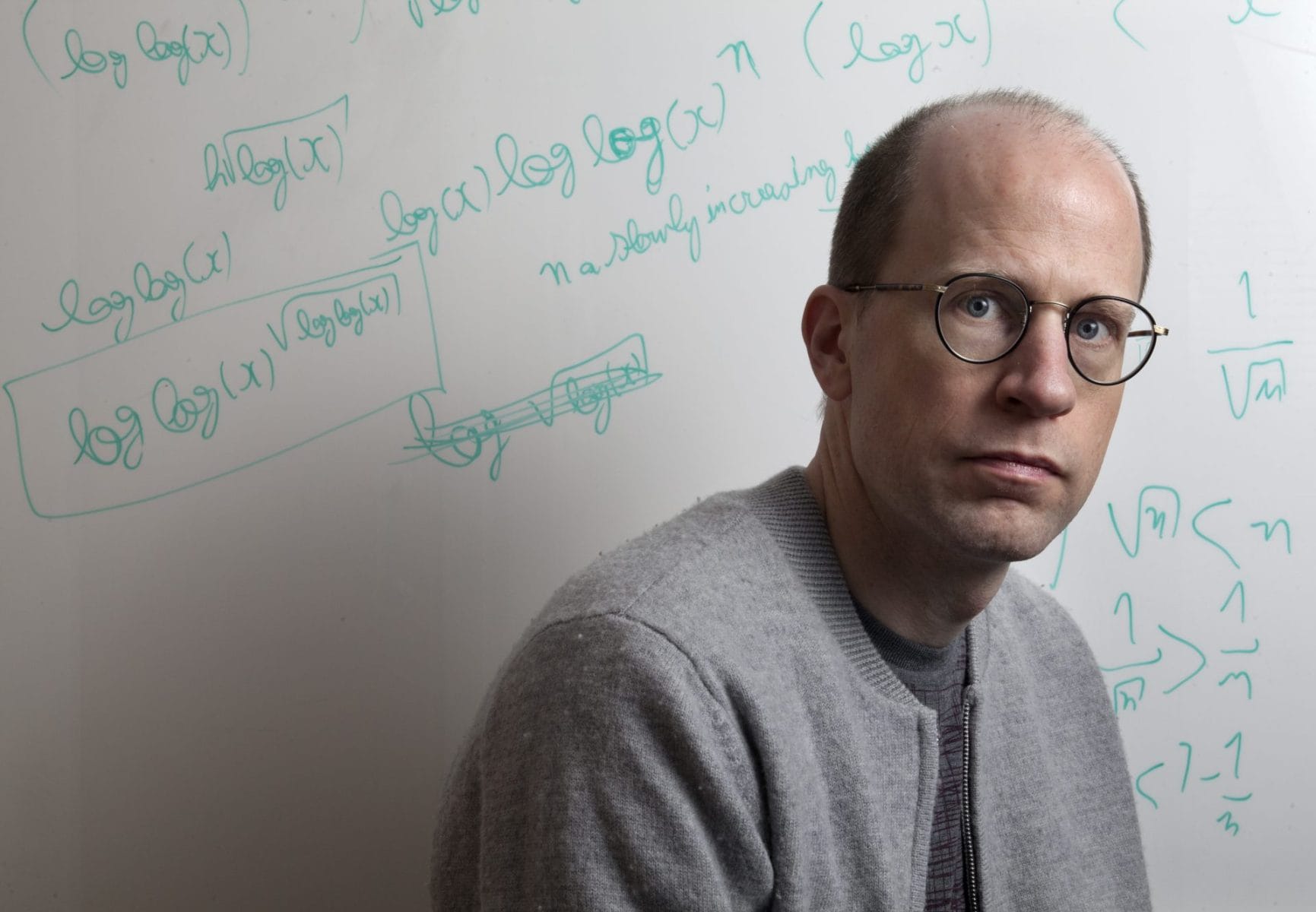

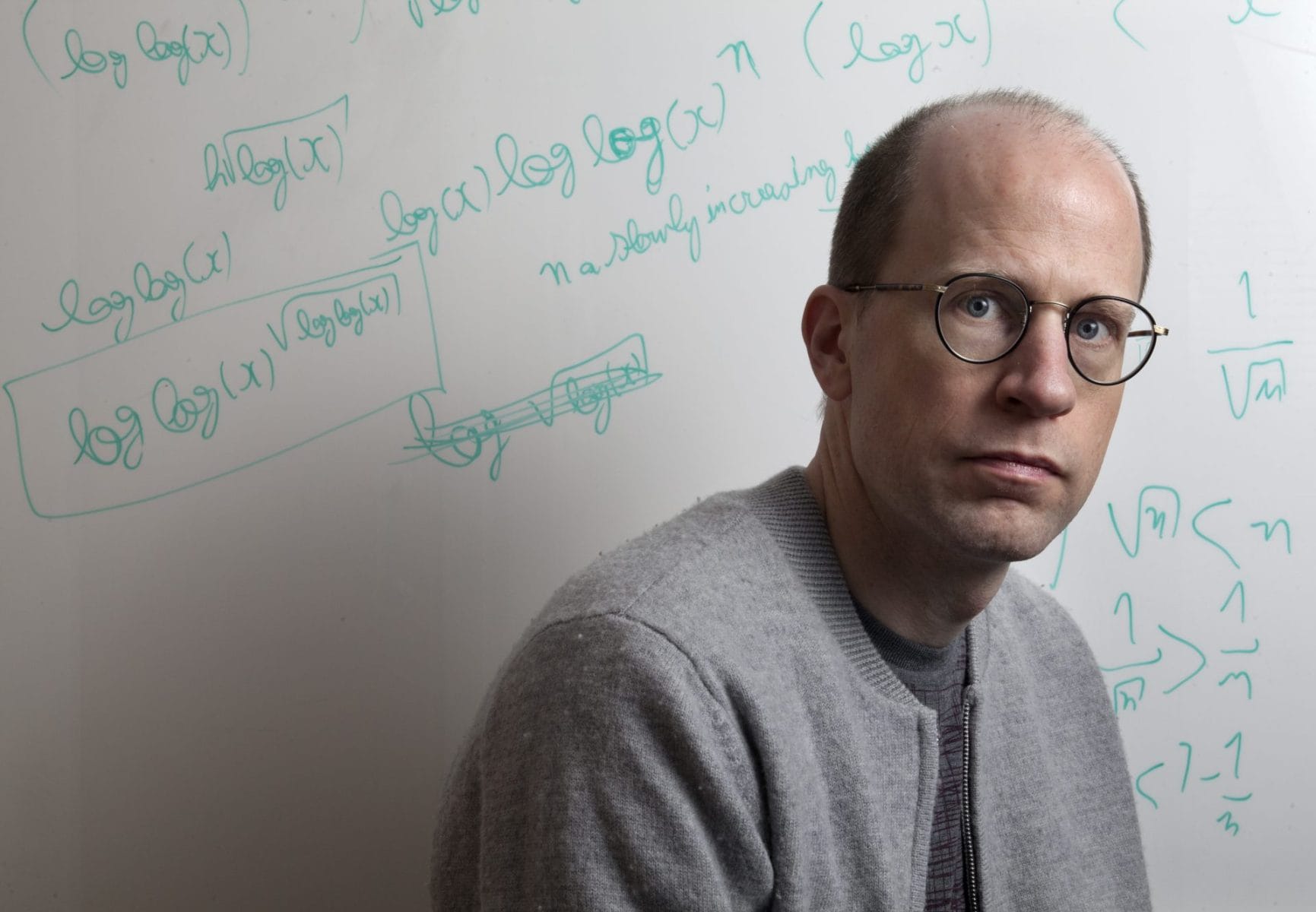

During our reporting, data scientist Christopher Wylie, best known as the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower, and I spoke to the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom, whose 2014 book foresaw the possibility that our world might be taken over by an uncontrollable artificial superintelligence.

A decade later, with AI companies racing toward Artificial General Intelligence with minimal oversight, Bostrom’s concerns have become urgent. What struck me most during our conversation was how he believes we’re on the precipice of a huge societal paradigm shift, and that it’s unrealistic to think otherwise. It’s hyperbolic, Bostrom says, to think human civilization will continue to potter along as it is.

Do we believe in Bostrom’s version of the future where society plunges into dystopia or utopia? Or is there a middle way? Judge for yourself whether his warnings still sound theoretical.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Christopher Wylie: To start, could you define what you mean by superintelligence and how it differs from the AI we see today?

Nick Bostrom: Superintelligence is a form of cognitive processing system that not just matches but exceeds human cognitive abilities. If we're talking about general superintelligence, it would exceed our cognitive capacities in all fields — scientific creativity, common sense, general wisdom.

Isobel Cockerell: What kind of future are we looking at — especially if we manage to develop superintelligence?

Bostrom: So I think many people have the view that the most likely scenario is that things more or less continue as they have — maybe a little war here, a cool new gadget there, but basically the human condition continues indefinitely.

But I think that looks pretty implausible. It’s more likely that it will radically change. Either for the much better or for the much worse.

The longer the timeframe we consider — and these days I don’t think in terms of that many years — we are kind of approaching this critical juncture in human affairs, where we will either go extinct or suffer some comparably bad fate, or else be catapulted into some form of utopian condition.

You could think of the human condition as a ball rolling along a thin beam — and it will probably fall off that beam. But it’s hard to predict in which direction.

Wylie: When you think about these two almost opposite outcomes — one where humanity is subsumed by superintelligence, and the other where technology liberates us into a utopia — do humans ultimately become redundant in either case?

Bostrom: In the sense of practical utility, yes — I think we will reach, or at least approximate, a state where human labor is not needed for anything. There’s no practical objective that couldn’t be better achieved by machines, by AIs and robots.

But you have to ask what it’s all for. Possibly we have a role as consumers of all this abundance. It’s like having a big Disneyland — maybe in the future you could automate the whole park so no human employees are needed. But even then, you still need the children to enjoy it.

If we really take seriously this notion that we could develop AI that can do everything we can do, and do it much better, we will then face quite profound questions about the purpose of human life. If there’s nothing we need to do — if we could just press a button and have everything done — what do we do all day long? What gives meaning to our lives?

And so ultimately, I think we need to envisage a future that accommodates humans, animals, and AIs of various different shapes and levels — all living happy lives in harmony.

Cockerell: How far do you trust the people in Silicon Valley to guide us toward a better future?

Bostrom: I mean, there’s a sense in which I don’t really trust anybody. I think we humans are not fully competent here — but we still have to do it as best we can.

If you were a divine creature looking down, it might seem like a comedy: these ape-like humans running around building super-powerful machines they barely understand, occasionally fighting with rocks and stones, then going back to building again. That must be what the human condition looks like from the point of view of some billion-year-old alien civilization.

So that’s kind of where we are.

Ultimately, it’ll be a much bigger conversation about how this technology should be used. If we develop superintelligence, all humans will be exposed to its risks — even if you have nothing to do with AI, even if you’re a farmer somewhere you’ve never heard of, you’ll still be affected. So it seems fair that if things go well, everyone should also share some of the upside.

You don’t want to pre-commit to doing all of this open-source. For example, Meta is pursuing open-source AI — so far, that’s good. But at some point, these models will become capable of lending highly useful assistance in developing weapons of mass destruction.

Now, before releasing their model, they fine-tune it to refuse those requests. But once they open-source it, everyone has access to the model weights. It’s easy to remove that fine-tuning and unlock these latent capabilities.

This works great for normal software and relatively modest AI, but there might be a level where it just democratizes mass destruction.

Wylie : But on the flip side — if you concentrate that power in the hands of a few people authorized to build and use the most powerful AIs, isn’t there also a high risk of abuse? Governments or corporations misusing it against people or other groups?

Bostrom: When we figure out how to make powerful superintelligence, if development is completely open — with many entities, companies, and groups all competing to get there first — then if it turns out it’s actually hard to align them, where you might need a year or two to train, make sure it’s safe, test and double-test before really ramping things up, that just might not be possible in an open competitive scenario.

You might be responsible — one of the lead developers who chooses to do it carefully — but that just means you forfeit the lead to whoever is willing to take more risks. If there are 10 or 20 groups racing in different countries and companies, there will always be someone willing to cut more corners.

Wylie: More broadly, do you have conversations with people in Silicon Valley — Sam Altman, Elon Musk, the leaders of major tech companies — about your concerns, and their role in shaping or preventing some of the long-term risks of AI?

Bostrom: Yeah. I’ve had quite a few conversations. What’s striking, when thinking specifically about AI, is that many of the early people in the frontier labs have, for years, been seriously engaged with questions about what happens when AI succeeds — superintelligence, alignment, and so on.

That’s quite different from the typical tech founder focused on capturing markets and launching products. For historical reasons, many early AI researchers have been thinking ahead about these deeper issues for a long time, even if they reach different conclusions about what to do.

And it’s always possible to imagine a more ideal world, but relatively speaking, I think we’ve been quite lucky so far. The impact of current AI technologies has been mostly positive — search engines, spam filters, and now these large language models that are genuinely useful for answering questions and helping with coding.

I would imagine that the benefits will continue to far outweigh the downsides — at least until the final stage, where it becomes more of an open question whether we end up with a kind of utopia or an existential catastrophe.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

This story is part of “Captured”, our special issue in which we ask whether AI, as it becomes integrated into every part of our lives, is now a belief system. Who are the prophets? What are the commandments? Is there an ethical code? How do the AI evangelists imagine the future? And what does that future mean for the rest of us? You can listen to the Captured audio series on Audible now.

The post Finding Meaning in Human Lives appeared first on Coda Story.

“Arwa it’s changed so much since you were last here, like you can’t imagine.” This was a message I received a few months ago from Yousra, the program coordinator at my charity INARA in Gaza. My last trip to Gaza was in December 2024. When I tried again a few months later, in February and in March, Israel denied me entry – no reason given. Back then, roughly a third of people attempting to enter on humanitarian or medical missions were being stopped, now that number is over half.

The images rolling through my mind of what I had seen over four humanitarian missions were already apocalyptic. I tried to picture “worse”. The children and adults I saw, in a crush of bodies, faces frozen in a grimace of despair and grief as they held out their empty pots. I tried to amplify the deadened eyes, the lethargic movements of starving people, and the soundtrack of desperate voices not quite drowned out by the incessant buzz of drones overhead.

Mohammed, INARA’s physical therapist in Gaza City, had sent me a couple videos of Souhaib, a little boy he’s treating. Souhaib had woken up one morning unable to move. He was admitted to the ICU and then spent a month in the hospital, but his condition did not change all that much.

The doctor’s preliminary diagnosis was acute flaccid paralysis – most likely a rare disease known as Guillain-Barre Syndrome (GBS), a rapid-onset muscle weakness caused by the immune system damaging the peripheral nervous system. But that diagnosis hasn’t been confirmed and cannot be confirmed in Gaza because the tests Sohaib needs aren’t available. All anyone can do is to give Sohaib physical therapy and hope that the paralysis doesn’t move to his involuntary nerves, his internal organs, which would lead to death.

Soubaib is malnourished, his head looks unnaturally big with its shock of blond hair, but Mohammad manages to coax smiles and giggles out of him as he moves his limp limbs. Souhaib is not the only child suffering in this way. There has been a spike in cases of suspected GBS. Where normally there would be one or two cases annually, now there are dozens, a byproduct of the lack of sanitation and lack of food. In Gaza, people’s bodies – especially those of children – have become too weak to fight infection.

“It’s like we’ve been issued a death sentence, only it’s a slow and excruciating execution” Mohammed messaged me on the day that famine, according to the United Nation’s IPC scale, was officially confirmed in Gaza City. Not that the people there needed a report to know that they were starving and being starved.

Hunger related deaths have soared to more than 400, including 145 children.

Ever since Israel implemented its full blockade on humanitarian trucks when it broke the ceasefire back in March there has been nothing “sustainable” or durable in what we, or frankly any of us in the humanitarian community, do or are allowed to do. We require Israel’s permission to pick up our pallets from the crossing point, to move waste, to fix bombed water lines, to cross through red zones and within the vast majority of Gaza, basically to do just about anything. In theory it’s meant to protect us from Israeli strikes. In reality, it’s always a gamble. Gaza is the deadliest place for humanitarians.

In May, Israel and the United States established the Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, replacing a pre-existing and proven system of at least 400 distribution points with just four located inside Israel’s red zones. Since then, more than a thousand people have been killed by Israeli guns, drones and tanks, just trying to get food from these locations. Doctors Without Borders, whose staff regularly receive mass influxes of casualties following violence at GHF sites, plainly stated: “This is not aid. This is orchestrated killing.’

Under international and U.S. pressure, Israel has been allowing a “trickle” of aid trucks to enter Gaza along with those carrying commercial goods destined for the market where few can afford the astronomical purchase costs.

A parcel of fresh vegetables weighing six kilograms (around 13 pounds) – not anything brought from the outside, but local produce from the few greenhouses still accessible – costs around $120. When the vegetables are delivered, I’m struck by how little children are grinning and grabbing at a cucumber like it’s candy on Halloween.

My INARA team goes to visit the home of a mother who showed up at our Gaza City clinic utterly beside herself and hysterical. Her twin boys’ bottoms scream with angry red diaper rash. Her husband holds out the can of baby formula with barely two scoops left. And one of her daughters ducks her head in shame as her mother shows our team her shaved head, raw with scabs from scratching because she had lice. The team returns with whatever they’ve been able to scratch together: a little shampoo, soap, baby formula and diapers.

One of the boys tells Yousra that it’s his birthday the next day. His mother says that all he has been asking for is bread. Not cake. Gazan children don’t even dare to dream of cake. Yousra returns, having searched for hours, on her own time, with a “bread cake”. As many loaves as she was able to find and a single candle.

The boy’s smile is pure magic.

“I had to do it,” Yousra told me later. “I just had to give him a little bit of joy.”

When I read the news, some days ago, about Israel dropping leaflets over Gaza City, ordering its one million residents to move south, I was in a panic.

I breathed a sigh of semi-relief when I heard from Yousra, when she finally got a signal on her phone.

And then Yousra sends a message and video that just shreds me.

“I didn’t want to leave my sons (7 and 10) alone while I was at work in case there was an evacuation order or a bombing, so I took them to my sister’s house” Yousra said. “We saw a very young girl lifting very heavy jerry cans, so I asked my older son to get out of the car to help her. I wanted my son to have this empathy, to help her and to know how exhausting her situation is.”

“Don’t worry”, though, Yousra continued. “We are strong enough to support others. We are here for our families, for the team, and for the people.”

Yet there is no strength in the world that can withstand the level of bombing that is raining hell beyond hell down on Gaza. And as Israel launched its ground offensive in Gaza City this week, sending in thousands of troops, there has been a crushing sense of finality. That people, forced to flee, are saying goodbye to their city, their homes, for the last time.

Our staff in Deir al-Balah, in the middle of the Gaza Strip, have been providing those evacuated from the north with fresh vegetable parcels purchased from the market. I was sent a video of a boy laughing as he bit into a tomato. “I can’t wait for my mom to make salad,” he says. “I’m so hungry!”

Earlier this week Mohammed tried to scout out a possible location for a tent for himself and his elderly parents. He sent me a video of the traffic jam along Gaza’s coastal road, people who are heeding Israel’s warning to leave the city.

Others are still stuck in the city, even as the Israeli tanks enter. “No one knows what to do”, he says. “I’m watching people in the street, they are just going around in circles, gasping and crying about how they can’t leave, don’t know where to go or how to get there.”

Mohammed, himself, feels deeply conflicted about leaving. “Arwa,” he tells me, “we didn’t evacuate when most people did last time, but I think we are going to have to this time. It burns me inside, it burns. It’s so painful. Where does this road end?” What answer is it possible to give him? “I wish,” he wrote, “I wish not to be displaced from our land. And to not be then displaced to Egypt. And to not then be displaced to South Sudan etc etc.”

He knows, like everyone in Gaza, how the Israelis and the Trump administration casually float ideas about where Gazans can be moved, how easily their land can be emptied.

That time has now come. Our primary care clinic, which was seeing 120 patients a day in Gaza City, has been moved further west, towards the coast. Four of our staff are refusing to leave and will continue to operate it for as long as they can.

The rest of our staff have now been forcibly evacuated further south, into tents and concrete rooms with no running water or electricity.

“You know Arwa,” Yousra says after spending 12 hours stuck in a sea of human misery making its way south, “it’s what you don’t see in the videos. It’s the women just sitting along the side of the road with one plastic bag between their legs, too tired to walk.” She’s struggling to find the words to express what she’s witnessed. And what keeps her going. “I want to live,” she tells me. “Not because I’m scared of death. I want to live so I can keep testifying to what we endured and have to endure every day while the world just watches and does nothing. And I want to live, so I can keep helping my people.”

A version of this article was published in our Sunday Read newsletter. Sign up here.

The post The Exodus of Hope appeared first on Coda Story.

In recent weeks, several small-scale protests have taken place across Russia, a rare sight since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine three years ago. Oddly, the demonstrators waved Soviet flags while holding banners demanding unrestricted access to digital platforms. It also remains unclear how the left-wing organizers secured permits to protest against the Kremlin’s latest move to further lock down and control the country’s online space.

Russia is in the process of constructing the most comprehensive digital surveillance state outside of China, deploying a three-layered approach that enforces the use of state-approved communication platforms, implements AI-powered censorship tools, and creates targeted tracking systems for vulnerable populations. The system is no longer about just restricting information, it's about creating a digital ecosystem where every click, conversation, and movement can be monitored, analyzed, and controlled by the state.

From September 1, 2025, Russia crossed a critical threshold in digital authoritarianism by mandating that its state-backed messenger app Max be pre-installed on all smartphones, tablets, computers, and smart TVs sold in the country.

Max functions as Russia's answer to China's WeChat, offering government services, electronic signatures, and payment options on a single platform. But unlike Western messaging apps with end-to-end encryption, Max lacks such protections and has been accused of gaining unauthorized camera access, with users reporting that the app turns on their device cameras "every 5-10 minutes" without permission. The integration with Gosuslugi, Russia's public services portal, means Max is effectively the only gateway for basic civil services: paying utility bills, signing documents, and accessing government services.

As Max was rolled out, WhatsApp and Telegram users found themselves unable to make voice calls, with connections failing or dropping within seconds. Officials justified blocking these features by citing their use by "scammers and terrorists," while a State Duma deputy warned that WhatsApp should "prepare to leave the Russian market".

The most chilling aspect of Russia's digital control system may be its targeted surveillance of migrants through another app called the Amina app. Starting September 1, foreign workers from nine countries, including Ukraine, Georgia, India, Pakistan and Egypt, must install an app that transmits their location to the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

This creates a two-tiered digital citizenship system. While Russian citizens navigate Max's surveillance, migrants face constant geolocation tracking. If the Amina app doesn't receive location data for more than three days, individuals are removed from official registries and added to a "controlled persons registry". This designation bars them from banking, marriage, property ownership, and enrolling children in schools, effectively creating digital exile within Russia's borders.

Russia's censorship apparatus has evolved beyond human moderators to embrace artificial intelligence for content control. Roskomnadzor, the executive body which supervises communications, has developed automated systems that scan "large volumes of text files" to detect references to illegal drugs in books and publications. Publishers can now submit manuscripts to AI censors before publication, receiving either flagged content or an all-clear message.

This represents a fundamental shift in how authoritarian states approach information control. As one publishing industry source told Meduza: "We've always assumed that the censors and the people who report books don't actually read them. But neural networks do. So now it's a war against the A.I.s: how to craft a book so the algorithm can't flag it, but readers still get the message".

The scope of Russia's digital surveillance ambitions became clear when the FSB, the country’s intelligence service, demanded round-the-clock access to Yandex's Alisa smart home system. While Yandex was only fined 10,000 rubles (about $120) for refusing – a symbolic amount that suggests the real pressure comes through other channels – the precedent is significant. The demand for access to Alisa represented what digital rights lawyer Evgeny Smirnov called an unprecedented expansion of the Yarovaya Law, which previously targeted mainly messaging services. Now, virtually any IT infrastructure that processes user data could fall under FSB surveillance demands.

Russia's digital control system follows the Chinese model but adapts it for different circumstances. While China built its internet infrastructure "with total state control in mind," Russia is retrofitting an existing system that was initially developed by private actors. This creates both opportunities and vulnerabilities.

The government's $660 million investment in upgrading its TSPU censorship system over the next five years signals long-term commitment to digital control. The goal is to achieve "96% efficiency" in restricting access to VPN circumvention tools. Meanwhile, new laws make VPN usage an aggravating factor in criminal cases and criminalizes "knowingly searching for extremist materials" online.

The infrastructure Russia is building today, from mandatory state messengers to AI censors to migrant tracking apps represents the cutting edge of digital authoritarianism. At least 18 countries have already imported Chinese surveillance technology, but Russia's approach offers a lower-cost alternative that's more easily transferable.. The combination of mandatory state apps, AI-powered censorship, and precision targeting of vulnerable populations creates a blueprint that other authoritarian regimes are likely to study and adapt.

To understand the impetus behind Russia’s digital Panopticon, look at Nepal: Russian analysts could barely contain their glee as they watched Nepal's deadly social media protests unfold. "Classic Western handiwork!" they declared, dismissing the uprising as just another "internet revolution" orchestrated by foreign powers. But their commentary revealed Moscow's deeper anxiety: what happens when you lose control of the narrative?

Russia isn't building its surveillance state to prevent what happened in Nepal, they're building it because they already lived through their own version. The 2021 Navalny protests proved that Russia's digitally native generation could organize faster than the state could respond. The difference is that Moscow's solution wasn't to back down like Nepal's now fallen government did. It was to eliminate the human networks first, then build the digital cage.

A version of this story was published in last week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Putin’s Panopticon appeared first on Coda Story.

Steve Witkoff, the United States Special Envoy to the Middle East, has said that the White House is putting together a “very comprehensive plan” to end the war in Gaza. Donald Trump agreed, claiming that “within the next two to three weeks” there would be a “pretty good, conclusive ending.” In the meantime, though, Israel has expanded its all-out assault on Gaza City, suspending aid operations even as the United Nations declares Gaza to be officially in the grip of a man-made famine. An Israeli spokesman said in Arabic that the evacuation of Gaza City was “inevitable”. The prospect of a ceasefire seems remote, though Qatari mediators have said Hamas has signed up to a ceasefire on terms nearly identical to those proposed by the U.S. and agreed to by Israel. But, as Trump has posted on Truth Social, Israel and the U.S. now believe that only by destroying Hamas and taking over Gaza, can the release of hostages be secured.

It doesn’t appear to matter how many more civilians die in the meantime. “Israel values the work of journalists, medical staff, and all civilians,” Benjamin Netanyahu posted on social media on August 25 responding to global condemnation following the deaths of five journalists in an attack on Nasser Hospital in Khan Yunis, in the southern Gaza Strip. Since the war in Gaza began in October, 2023, at least 197 journalists have been killed according to the Committee to Protect Journalists which has described Israel’s actions as “the deadliest and most deliberate effort to kill and silence journalists that CPJ has ever documented.” Al Jazeera, the Qatari-based news network, puts the number at over 270.

Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni, speaking at a Catholic festival in Rimini, said the killings were “an unacceptable attack on press freedom and on all those who risk their lives to report the tragedy of war.” British prime minister Keir Starmer called the bombing in Khan Yunis “completely indefensible.” On X, the German foreign ministry said it had “repeatedly called on the Israeli government to allow immediate independent foreign media access and afford protection for journalists operating in Gaza.” Spain described it as “a flagrant and unacceptable violation of international humanitarian law.”

Given the near universal condemnation, will anything be done to hold Israel to account? “More governments are showing a willingness in recent months to call out Israel for its failure to protect journalists and to call for transparent investigations into their killings,” said Jodie Ginsberg, the chief executive of the Committee to Protect Journalists. “But,” she told Coda, “they still stop short on taking any concrete measures - such as sanctions, or conditions on trade agreements or weapons sales - that could force Israel to uphold its obligations under international law.”

Earlier this month, on August 10, Al Jazeera journalist Anas al-Sharif, was killed in Gaza City alongside several of his colleagues. Israel admitted to targeting al-Sharif, describing him as “masquerading” as a journalist. “A terrorist is a terrorist,” Israeli diplomats said, “even if Al Jazeera gave him a press badge.”

According to intelligence sources who spoke to Israeli publication +972 Magazine, the IDF established a special “Legitimization Cell” after October 7, tasked not with security operations but with gathering intelligence to bolster Israel's media image. The unit specifically sought to identify Gaza-based journalists it could portray as Hamas operatives, driven by anger that Palestinian reporters were “smearing Israel's name in front of the world.” Whenever global criticism intensified over the killing of journalists, the cell was instructed to find intelligence that could publicly counter the narrative. "If the global media is talking about Israel killing innocent journalists, then immediately there's a push to find one journalist who might not be so innocent—as if that somehow makes killing the other 20 acceptable," one intelligence source told +972 Magazine. Intelligence gathered was passed directly to American officials through special channels, with officers told that their work was vital to allowing Israel to continue the war without international pressure.

In its initial inquiry into Monday’s bombing of Nasser Hospital in Khan Yunis, Israel claimed a camera at the hospital was “being used to observe the activity of IDF troops, in order to direct terrorist activities against them.” International journalists have no independent access to Gaza. It would be, Ginsberg said, “one way to help force a change in the narrative being pushed by Israel that all Gazan journalists are terrorist operatives and therefore none can be trusted.” Ginsberg told Coda that of the cases of journalists and media workers killed by Israel, CPJ has so far “deemed 26 to be deliberate targeting… these are the cases where we are clear that Israel would have known the individuals killed were journalists and nevertheless targeted them.”

Journalists, as civilians, are protected under international law. Targeting them is a war crime. Yet, Ginsberg notes, since “international journalists and human rights investigators do not have access to Gaza,” it has “hampered documentation.” And “more disturbingly,” she added, “the dehumanization of Gazan journalists and Gazans more generally means there has not been the collective outrage that should accompany any killing let alone killings of this magnitude.”

Israel has already said that the deaths of journalists in the attack on Nasser Hospital were a "tragic mishap" that resulted from legitimate security operations. The recent UN Security Council vote on an immediate ceasefire (14 out of 15 members supporting, only the U.S. withholding) signals Israel’s growing isolation. But American support is all Israel needs to continue its war. As the killings of journalists continue to be explained away, without evidence, as the killing of terrorists, the window for independent reporting in Gaza has likely closed. The systematic targeting of Gazan journalists isn't collateral damage, it's strategic silencing ahead of what may be the war's final phase.

A version of this story was published in our Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post The Systematic Silencing of Gaza appeared first on Coda Story.

In September, the International Criminal Court will conduct a confirmation of charges hearing against warlord Joseph Kony. Leader of the once notorious rebel group Lord’s Resistance Army and the subject of ICC warrants dating back two decades, Kony is still at large, still evading arrest.

Thirteen years ago, a group of American do-gooders tried to do something about this.

The NGO Invisible Children published a 30-minute YouTube video with high hopes. With their film ‘Kony 2012’, they sought to stop the Lord’s Resistance Army, which had kidnapped, killed and brought misery to families across several Central African nations since the late 1980s. The video opens with our blue orb home spinning in outer space as the director reminds us of our place in time. “Right now, there are more people on Facebook than there were on the planet 200 years ago,” he says. “Humanity's greatest desire is to belong and connect, and now, we see each other. We hear each other. We share what we love. And this connection is changing the way the world works.” In other words, the technology of connection will solve this problem.

Despite the uber virality of the film,100 million plus views nearly overnight, Kony remains a free man, though much more infamous, and his victims didn’t get all the help they needed. The campaign seemed to embody slacktivism at its most poisonous: the high hope that you can change the world from your sofa.

“Hope,” Gloria Steinem once wrote, “is a very unruly emotion.” Steinem was writing about US politics in the Nixon era but the observation holds. Hope is at the core of how many of us think about the future. Do we have hope? That’s good. It’s bad if we have the opposite – despair, or even cynicism.

Former CNN international correspondent, Arwa Damon knows this unruly quality of hope firsthand. For years she worked as a journalist in conflict zones. Now she helps kids injured by war through her charity called INARA. She discussed this work last month at ZEG Fest, Coda’s annual storytelling festival in Tbilisi. In war, Damon has seen how combatants toy with hope, holding out the possibility of more aid, less fighting only to undermine these visions of a better tomorrow. This way, she says they snuff out resistance. This way they win.

In seeing this, and in surviving her own close calls, Damon told the Zeg attendees, she realized she didn’t need hope to motivate her. “Fuck hope,” she said to surprised laughter.

So what motivates her to keep going? “Moral obligation,” she said. After everything she has seen, she simply cannot live with herself if she doesn’t help. She doesn’t need to hope for an end to wars to help those injured by them now. In fact, such a hope might make her job harder because she’d have to deal with the despair when this hope gets dashed, as it will again and again. She can’t stop wars, but she can, and does, help the kids on the front lines.

Most of us haven’t crawled through sewers to reach besieged Syrian cities or sat with children in Iraq recovering from vicious attacks. And most of us don’t spend our days marshalling aid convoys into war zones. But we see those scenes on our phones, in near real time. And many of us feel unsure what to do with that knowledge because most of us would like to do something about these horrors. How do we deal with this complex emotional reality? Especially since, even if we are not in a physical war zone, the information environment is packed with people fighting to control the narratives. In this moment of information overload and gargantuan problems, could clinging onto hope be doing us more harm than good?

Emotion researchers like Dr. Marc Brackett will tell you that instead of thinking of emotions as good or bad, we can think of them as signals about ourselves and the world around us. And we could also think about them as behaviors in the real world. Dr. Brackett, who founded and runs the Center for Emotional Intelligence at Yale, said hope involves problem solving and planning. Think about exercising, which you might do because you hope to improve your body. In those cases hope could prove a useful motivator. “The people who only have hope but not a plan only really have despair,” Dr. Brackett explained “because hope doesn't result in an outcome.”

Developing a workout plan seems doable. Developing a plan to capture a warlord or stop kids from suffering in wars is a good deal more complex. The 2010s internet gave us slacktivism and Kony 2012, which seems quaint compared to the 2020s internet with its doom scrolling, wars in Ukraine and Gaza and much more misery broadcast in real time. What should we do with this information? With this knowledge?

Small wonder people tune out, or in our journalism jargon, practice news avoidance. But opting out of news doesn’t even provide a respite. Unless you’ve meticulously pruned your social media ecosystem, the wails of children, the worries about climate change, the looming threats of economic disruption or killer machines, those all can quickly crowd out whatever dopamine you got from that video of puppy taking its first wobbly steps. But paradoxically, the pursuit of feeling good, might actually be part of the problem of hope.

I took these questions about hope to Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett, an acclaimed psychologist and neuroscientist. She too talked less about our brains and more about our behaviors. The author of, among other things, How Emotions are Made, Dr. Barrett noted that we might experience hope in the moment as pleasant or energizing and it helps with creating an emotional regulation narrative. Meaning: we can endure difficulty in the present because we believe tomorrow we will feel better, it will get better. However, Barrett said hope alone as a motivator “might not be as resistant to the slings and arrows of life.” If you assume things will get better, and then they don’t, how do you keep going?

“I think people misunderstand what's happening under the hood when you're feeling miserable,” she added. “Lots of times feel unpleasant not because they're wrong but because they're hard.”

I told Dr. Barrett about Damon’s belief that she keeps going because of moral obligation and she again looked at the emotional through the behavioral. “There is one way to think about moral responsibility as something different than hope,” she said, “but if hope is a discipline and you're doing something to make the parts of the world different you could call it the discipline of hope.” This could be a more durable motivation, she suggested, than one merely chasing a pleasant sensation that tomorrow will be better. “My point is that, if your motivation is to feel good, whatever it is you are doing, your motivation will wane.”

After ‘Kony 2012’ shot to astonishing success, in terms of views, the creators raised tens of millions of dollars but achieved little on the ground – an early lesson in the limits of clicktivism. Once upon a time American do-gooders hoped they’d help Ugandan children simply by making a warlord infamous, now the viralness of Kony 2012 feels like a window into a cringey past, a graveyard of hopes dashed. But maybe we just grew up. Maybe our present time and this information environment full of noise and warring parties asks more of us. Maybe hope has a place but among a whole emotional palate of motivations instead of a central pillar keeping us moving forward. Because let’s be honest: we may never get there. Hope, as the experts told me, doesn’t work without a plan. And, raising hopes, especially grand ones like changing global events from your smartphone, only to have them dashed can actually prompt people to disengage, to despair maybe, or even to embrace cynicism so they don’t have to go through the difficult discipline of hope and potential disappointment.

One day, during the start of the pandemic, when my home doubled as my office, I got a piece of professional advice I’ve held tight. A therapist who works with ER doctors shared with a group of us journalists that when we work on tasks that seem never ending, burnout is more likely. To prevent it, he advised that we right-size the problem. Put down the work from time to time, celebrate our achievements (especially in tough times), develop rituals and build out perspective to nourish us as we keep doing the work.

The pandemic ended but we bear the scars and warily look out at a horizon full of looming troubles, most of them way outside the control of any one of us. Both Dr. Marc Brackett and Dr. Lisa Feldman Barrett reminded me: emotions are complex and humans aren’t motivated by just one thing. But no matter what mountain we want to climb we would all do well to adopt this conception of hope as a discipline rather than just a feeling. Because in this environment, there’s always someone on the other side betting we’ll give up in despair.

A version of this story was published in last week’s Sunday Read newsletter. Sign up here.

The post The Danger of Hope appeared first on Coda Story.

I was invited to deliver a keynote speech at the ‘AI for Good Summit’ this year, and I arrived at the venue with an open mind and hope for change. With a title “AI for social good: the new face of technosolutionism” and an abstract that clearly outlined the need to question what “good” is and the importance of confronting power, it wouldn’t be difficult to guess what my keynote planned to address. I had hoped my invitation to the summit was the beginning of engaging in critical self-reflection for the community.

But this is what happened. Two hours before I was to deliver my keynote, the organisers approached me without prior warning and informed me that they had flagged my talk and it needed substantial altering or that I would have to withdraw myself as speaker. I had submitted the abstract for my talk to the summit over a month before, clearly indicating the kind of topics I planned to cover. I also submitted the slides for my talk a week prior to the event.

Thinking that it would be better to deliver some of my message than none, I went through the charade or reviewing my slide deck with them, being told to remove any reference to “Gaza” or “Palestine” or “Israel” and editing the word “genocide” to “war crimes” until only a single slide that called for “No AI for War Crimes” remained. That is where I drew the line. I was then told that even displaying that slide was not acceptable and I had to withdraw, a decision they reversed about 10 minutes later, shortly before I took to the stage.

Looking at this year’s keynote and centre stage speakers, an overwhelming number of them came from industry, including Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon. Out of the 82 centre stage speakers, 37 came from industry, compared to five from academia and only three from civil society organisations. This shows that what “good” means in the "AI for Good" summit is overwhelmingly shaped, defined, and actively curated by the tech industry, which holds a vested interest in societal uptake of AI regardless of any risk or harm.

“AI for Good”, but good for whom and for what? Good PR for big tech corporations? Good for laundering accountability? Good for the atrocities the AI industry is aiding and abetting? Good for boosting the very technologies that are widening inequity, destroying the environment, and concentrating power and resources in the hands of few? Good for AI acceleration completely void of any critical thinking about its societal implications? Good for jumping on the next AI trend regardless of its merit, usefulness, or functionality? Good for displaying and promoting commercial products and parading robots?

Any ‘AI for Good’ initiative that serves as a stage that platforms big tech, while censoring anyone that dares to point out the industry’s complacency in enabling and powering genocide and other atrocity crimes is also complicit. For a United Nations Summit whose brand is founded upon doing good, to pressure a Black woman academic to curb her critique of powerful corporations should make it clear that the summit is only good for the industry. And that it is business, not people, that counts.

This is a condensed, edited version of a blog Abeba Birhane published earlier this month. The conference organisers, the International Telecommunication Union, a UN agency, said “all speakers are welcome to share their personal viewpoints about the role of technology in society” but it did not deny demanding cuts to Birhane’s talk. Birhane told Coda that “no one from the ITU or the Summit has reached out” and “no apologies have been issued so far.”

A version of this story was published in the Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post AI, the UN and the performance of virtue appeared first on Coda Story.

Kyiv's Desniansky District Court has formally recognized a same-sex couple as a family, marking the first legal precedent of its kind in Ukraine, human rights organization Insight LGBTQ announced on July 3.

Ukraine does not currently recognize same-sex marriages or partnerships, and this court ruling may serve as a critical legal milestone in expanding rights for LGBTQ families.

The case involves Zoryan Kis, first secretary of Ukraine's Embassy in Israel, and his partner Tymur Levchuk, who have lived together since 2013 and were married in the U.S. in 2021.

The court ruled on June 10 that their relationship constitutes a de facto marriage, establishing them as a family under Ukrainian law.

The ruling comes after Ukraine's Foreign Ministry refused to acknowledge Levchuk as Kis' family member, denying him spousal rights to accompany Kis on his diplomatic posting to Israel. In response, the couple filed a legal complaint in September 2024.

In its decision, the court cited both the Ukrainian Constitution and precedents from the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which requires states to ensure legal recognition and protection for same-sex families.

Evidence considered by the court included shared finances, property, witness testimony, joint travel records, photographs, correspondence, and other documents establishing a long-term domestic partnership.

"A very big and important step toward marriage equality in Ukraine, and a small victory in our struggle for 'simple family happiness' for Ukrainian diplomats," Kis wrote on Facebook.

"Now we have a court ruling that confirms the feelings Tymur Levchuk and I have for each other," he added, thanking the judge who heard the case.

Public support for LGBTQ rights in Ukraine has grown in recent years, particularly since the start of Russia's full-scale invasion. According to a 2024 poll by the Kyiv International Institute of Sociology, 70% of Ukrainians believe LGBTQ citizens should have equal rights.

Despite shifting public opinion, legislative progress remains slow. A draft law recognizing civil partnerships, introduced by Holos party lawmaker Inna Sovsun in March 2023, has not advanced in parliament due to a lack of approval from the Legal Policy Committee.

The proposed bill would legalize civil partnerships for both same-sex and heterosexual couples, offering them inheritance, medical, and property rights, but not the full status of marriage.

The Kyiv IndependentAndrea Januta

The Kyiv IndependentAndrea Januta

Ukrainian journalist Vladyslav Yesypenko was released on June 20 after more than four years of detention in Russian-occupied Crimea, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported.

Yesypenko, a freelance contributor to Crimea.Realities, a regional project of RFE/RL's Ukrainian Service, reported on various issues in Crimea before being detained by Russia’s FSB in March 2021.

He was accused of espionage and possession of explosives, charges he denied, and later sentenced to five years in prison by a Russian-controlled court.

Yesypenko said he was tortured, including with electric shocks, to force a confession, and was denied access to independent lawyers for nearly a month after his arrest.

RFE/RL welcomed his release, thanking the U.S. and Ukrainian governments for their efforts. Yesypenko has since left Russian-occupied Crimea.

“Vlad was arbitrarily punished for a crime he didn’t commit… he paid too high a price for telling the truth about occupied Crimea,” said RFE/RL President Steven Kapus.

During his imprisonment, Yesypenko became a symbol of press freedom, receiving several prestigious awards, including the Free Media Award and PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award.

His case drew support from human rights groups, the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, and international advocates for media freedom.

Russia invaded and unlawfully annexed Crimea in 2014, cracking down violently on any opposition to its regime.

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Kremlin toughened its grip on dissent, passing laws in March 2022 that prohibit what authorities label as "false" criticism of Russia's war.

The Kyiv IndependentDaria Shulzhenko

The Kyiv IndependentDaria Shulzhenko

Last week, Donald Trump was on a glitzy, bonhomous trip through Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates. Amidst the talk of hundreds of billions of dollars signed in deals, the rise of Gulf states as potential AI superpowers, and gifts of luxury jetliners, it was announced that the Trump administration had agreed arms deals worth over $3 billion with both Qatar and the UAE.

Democrats are looking to block the deals. Apart from the potential corruption alleged by legislators – the many personal deals the president also inked while on his trip – they criticized the sale of weapons to the UAE at a time when it was prolonging a civil war in Sudan that the U.N. has described as “one of the worst humanitarian crises of the 21st century.”

Earlier this month, a Sudanese politician said Trump’s trip to the Gulf was a “rare opportunity” to make a decisive intervention in a war that is now into its third year. In 2023, the U.S., Saudi Arabia, Sudan’s army and the rebels signed a peace treaty in Jeddah. It lasted a day. Despite the involvement of both Saudi Arabia and the UAE in the conflict – Sudan has accused the UAE of being directly responsible for the May 4 drone attacks on the city of Port Sudan – there was no mention of it during Trump’s visit.

Since April 2023, Sudan has been convulsed by civil war. The fighting – between the Sudanese army and the RSF rebel forces, primarily comprising Janjaweed militias that fought on the side of the army in the Darfur conflict back in 2003 – has cost thousands of lives and displaced over 12 million people. Tens of millions are starving.

In May, the fighting intensified. But on Monday, Sudan’s army chief, Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, announced the appointment of a new prime minister – career diplomat Kamal Idris. The African Union said Idris’s appointment was a “step towards inclusive governance.” But there is little sign of the fighting stopping. In fact, Port Sudan, where much of the humanitarian aid entered into the country, was targeted in drone attacks this month, forcing the U.N. to suspend deliveries. The Sudanese army has said renewed fighting with the RSF will force it to shut down critical infrastructure that its neighbor South Sudan needs to export its oil. South Sudan’s economy is almost wholly dependent on oil. The threat of economic collapse might force South Sudan, which became independent in 2011, to join in the Sudanese civil war.

This week, the Trump administration was accused of “illegally” dispatching migrants to South Sudan. A judge said such an action might constitute contempt, but the Department of Homeland Security claimed the men were a threat to public safety. “No country on Earth wanted to accept them,” a spokesperson said, “because their crimes are so uniquely monstrous and barbaric.” The Trump administration’s extraordinary decision to deport migrants to South Sudan, a country on the verge of violent collapse and neighboring a country mired in civil war, is in keeping with his attitude towards the region. The decision, for instance, to shut down USAID only exacerbated the food crisis in Sudan, with soup kitchens closing and a loss of 44% of the aid funding to the country.

With Trump fitfully engaging in all manner of peace talks, from Gaza to Kyiv to Kashmir, why is Sudan being ignored? Given the transactional nature of Trump’s diplomacy, is it because Sudan has nothing Trump wants? In April, for instance, the Trump administration attempted to broker peace between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Rwanda in Washington, offering security in exchange for minerals. In this colonial carving up of resources, perhaps Trump is content to let his friends in the UAE control Sudan’s gold mines and ignore a civil war he might otherwise try to stop.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Sudan’s forgotten war appeared first on Coda Story.