Zelensky Expresses Wary Optimism About Ukraine Peace Plan

© Pool photo by Kay Nietfeld

© Pool photo by Kay Nietfeld

© Kirsty Wigglesworth/Associated Press

Lithuanian companies allegedly helped export Russian liquefied petroleum gas to Ukraine by using misleading certificates tied to Lithuania’s Orlen Lietuva refinery, LRT reported, referring to a new investigation by journalistic research center Siena. The report details how small amounts of European-produced fuel were used to disguise much larger volumes of Russian gas, circumventing Ukraine’s sanctions.

LRT reports that Lithuanian fuel company Jozita and Gazimpeks, a firm with links to the Russian energy sector, allegedly sent thousands of tons of Russian liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) to Ukraine using questionable documents. According to Siena, both companies purchased limited quantities of LPG from Lithuania’s Orlen Lietuva and used those origin certificates to export significantly larger volumes of fuel.

Ukrainian court documents referenced in the report suggest that officials suspected fuel shipments were “diluted”—a process of mixing small amounts of European LPG with Russian product to mask its origin. The investigation states that under Ukrainian law, if such mixing occurs, the fuel can still retain its European classification. This created a loophole that companies reportedly exploited to import Russian fuel despite sanctions, LRT says.

Siena’s report highlights the connections between Gazimpeks and Russia’s sanctioned energy sector. The company was run until July 2024 by Nikolai Yeliseev, a Russian citizen and former head of Rosneft—Russia’s second-largest state-owned energy company, which remains under EU and US sanctions.

Gazimpeks is owned by Oksana Yeliseeva, who acquired Lithuanian citizenship in 2021, according to LRT. Investigators claim she did so by falsely stating that she had renounced her Russian citizenship. The report adds that she continued using a Russian passport for international travel after obtaining Lithuanian papers.

© Australian Prime Minister Office, via Associated Press

Russia has turned down a proposal for a Christmas ceasefire, with Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov stating that Moscow seeks "not a truce that would give Kyiv a respite and an opportunity to prepare for the continuation of the war, but a full-fledged peace," according to Russian news agency Interfax.

The Russian representative emphasized that Moscow's position "is well known both in the United States and in Ukraine" and stressed that Russia wants to achieve its objectives.

"The question now is whether we are moving toward what President Trump calls a deal, or not," Peskov claimed. "If the Ukrainians have and begin to be dominated by a desire to replace moving toward a deal with immediate unviable solutions, then we are hardly ready to participate in this."

The rejection comes after German Federal Chancellor Friedrich Merz proposed that Russia arrange a Christmas truce. He expressed hope that Russian authorities "have remnants of humanity and can leave people alone for a few days."

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy had previously said ated that both Ukraine and the United States supported the idea of a truce during Christmas and New Year holidays.

"Friedrich has indeed proposed such an idea. He announced it today both publicly and during our conversations. The United States of America supports this idea. As President, I certainly support it as well," Zelenskyy told journalists, responding to a question about the German chancellor's proposal. "I believe that an energy ceasefire is also fine, and we will support any ceasefire. Overall, we support both Europe and the United States in steps aimed at ending the war."

However, Zelenskyy said that "many things, of course, depend on Russia's political will in this regard," while also emphasizing that "much also depends on our work on the documents."

© Ezra Acayan for The New York Times

© Alasdair Pal/Reuters

© Vladimir Zivojinovic for The New York Times

© Jack Taylor/Reuters

© Saher Alghorra for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Alex Fu

© Ozan Kose/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Pool photo by Kirsty Wigglesworth

© AAP Image/Dan Himbrechts, via Reuters

© AAP Image/Steven Markham, via Reuters

© Laura Cavanaugh/FilmMagic, via Getty Images

In Australia, during a shooting at Sydney’s Bondi Beach, 87-year-old Ukrainian immigrant Alex Kleytman, born in Ukraine's Odesa, survived the Holocaust and had lived in the country for nearly 60 years. He was killed while trying to protect his wife, NBC News reports.

The advocacy group, the Executive Council of Australian Jewry, said more than 3,700 anti-Jewish incidents occurred in Australia during the two years following the Hamas attack in 2023, per NPR. Hamas launched a surprise attack on Israel, killing over 1,200 people and taking more than 250 hostages. Among the victims were around 40 foreigners from over 30 countries.

On 14 December, during a festival celebrating the Jewish holiday of Hanukkah at Bondi Beach in Sydney, a shooting occurred. At least 15 people were killed, including one of the attackers, and dozens were injured. Australian police classified the attack as a terrorist act and an antisemitic incident, per Reuters.

Alex Kleytman survived the Holocaust alongside his mother and younger brother, enduring Siberia. This region of Russia served as a primary site for political repressions under the Soviet Union, housing vast networks of exile settlements, labor camps, and Gulags. After World War II, he emigrated from Ukraine to Australia.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Larisa Kleytman, also a Holocaust survivor. The couple had been together for nearly 60 years.

Moments before the tragedy, she heard several loud sounds like “booms” and immediately saw her husband fall to the ground.

After the attack, Larisa Kleytman admitted she was “shocked” and “confused” and is trying to understand what happened.

Today, there are interesting updates from the Russian Federation.

Here, а series of aviation accidents far from the battlefield in Ukraine shows Russia’s air fleet is imploding at an unprecedented rate. The Russian sacrifice of expensive high-tech military to finance low-tech operations in Ukraine is now backfiring and leading to even greater and in many cases irreplaceable losses.

Russia’s aviation suffered another major blow with the crash of its last operational Antonov-22, a 50-year-old aircraft undergoing a post-repair test flight, which broke apart midair over the Ivanovo region, falling into a local water reservoir.

Russian sources shared footage showing the crash of the An-22 military transport aircraft in Russia’s Ivanovo Oblast on 9 December.

— Euromaidan Press (@EuromaidanPress) December 14, 2025

The video captures the moment the plane breaks apart mid-air before plunging into the Uvod Reservoir. All 7 crew members were killed. Preliminary… pic.twitter.com/WPkXRO0ssN

Seven crew members were on board, and the Russian Ministry of Defense tried to frame the crash as a routine accident, yet even Russian state media quietly acknowledged the aircraft had exceeded any realistic airworthiness limits. Eyewitnesses reported that sections of the fuselage detached before impact, confirming structural fatigue long suspected in Russia’s aging transport fleet.

Critically, this was the last active An-22, a platform Russia continued using simply because it lacked the capacity to replace it. The crash underscores a deeper problem: nearly four years of war, sanctions, and frantic military use have pushed a legacy fleet far past safe operating thresholds, as this incident is far from isolated, but part of a rapidly accelerating pattern of systemic failure.

The An-22 disaster came just one day after another grotesque aviation failure, this time inside a hangar. Two Russian Su-34 fighter-bomber pilots were killed instantly when their ejection seats suddenly activated, launching them into the ceiling of the hangar they were still in.

Officially, it was labeled an accident, noted that the pilots had sustained injuries incompatible with life, but in Russia’s collapsing aviation environment, the line between accident, sabotage, and incompetence has become increasingly blurred. Magyar’s Birds, Ukraine’s well-known drone unit, openly hinted after the event that Russian pilots remain legitimate targets for Ukrainian intelligence, suggesting that such accidents may not always be accidental. Even if this case was simply the result of neglected maintenance, the psychological effect is the same: panic within the ranks and a growing fear that anything, from a seat to a sensor, can kill you without warning.

The catalogue of recent Russian aviation incidents shows a consistent pattern of basic failures. In the last months alone, a Su-35 crashed while landing at Kubinka after being scrambled to counter a Ukrainian drone attack, with the pilot surviving but in critical condition.

A Mig-31 in the Lipetsk region went down after its landing gear malfunctioned mid-flight, with both pilots severely injured despite ejecting. A Su-30SM in Karelia failed to land entirely, killing both aviators. Importantly, these are not frontline shoot-downs but malfunctions during routine flights, with the Russian helicopter fleet suffering the same fate.

A Ka-52 accident destroyed the helicopter along with killing its crew, while a far more damaging crash occurred in Dagestan when a Ka-226 carrying senior engineering specialists fell from the sky. Among the dead were the Kizlyar Electromechanical Plant’s chief engineer, chief instructor for construction, and the deputy director, specialists whose expertise cannot be replaced quickly, if at all.

The Kizlyar facility produces critical avionics and control systems for Su and Mig fighter and fighter-bomber jets, meaning this single crash inflicted consequences far beyond the loss of an airframe, harming Russia's war efforts in Ukraine directly.

Small accidents were just the beginning, followed by big failures, and what we see now is the start of the total collapse, with the An-22 literally falling apart in the sky. Spare parts shortages, loss of qualified technicians, and reliance on cannibalized Soviet-era components have turned routine Russian operations into high-risk events.

They are particularly dangerous not just because Russia is losing aircraft but because it is losing key specialists, the only people who know how to keep this old machinery running. Replacing pilots is difficult enough; replacing engineers with decades of knowledge about Soviet-era systems is far worse for an army, continuing to rely on old equipment.

Overall, taken together, these events show an air force approaching structural collapse. Combat losses over Ukraine already strain Russia’s fleet, but the surge of accidents deep in the rear exposes a different crisis: Russia can no longer maintain the aircraft it still has.

As sanctions tighten and electronic components become harder to source, the frequency of such failures will only increase. The collapse will not be sudden but cumulative, aircraft by aircraft, crew by crew, until Russia's once formidable air fleet becomes unsustainable, held together by aging parts, improvised fixes, and luck that is steadily running out.

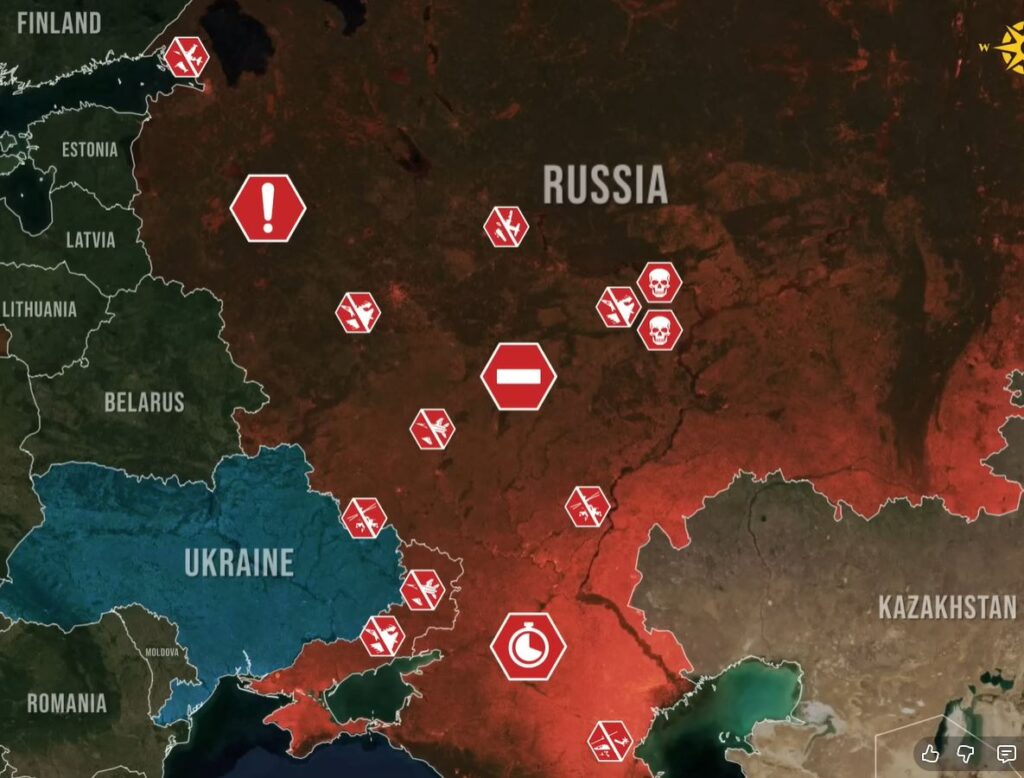

In our regular frontline report, we pair up with the military blogger Reporting from Ukraine to keep you informed about what is happening on the battlefield in the Russo-Ukrainian war.

The new Russian drone is used not only for strikes on ground targets but also for hunting Ukrainian aircraft and helicopters. Ukraine's Defense Intelligence reports indicate that the new Geran modification includes components from the US, the UK, Germany, Japan, Switzerland, and Taiwan.

For the production of this drone, Russia used a combination of Soviet-era weaponry and modern Western electronics. The technology may potentially be transferred to Iran and other Russian allies.

This is direct evidence of systemic failures in export controls and sanctions, the consequences of which could extend far beyond the war in Ukraine.

To expand combat capabilities, the Russians adapted the old Soviet R-60 air-to-air missile for launch from the drone. The missile, equipped with the APU-60-1MD aviation launcher, is mounted on a special bracket on the upper front part of the Geran fuselage.

The UAV is equipped with two cameras, one in the nose and another behind the launcher. Video and control commands are transmitted through a Chinese mesh modem, Xingkay Tech XK-F358, allowing the operator to remotely manage the combat situation.

Navigation and inertial units remain typical for other Geran drones, but in electronic warfare (EW) conditions, a 12-channel jamming-resistant “Kometa” module is used.

The electronics also include:

The likely operational principle involves sending an image to the operator, who commands missile launch if an aircraft or helicopter enters the target zone. The R-60 missile’s infrared seeker then independently locks onto the target.

“Another probable method involves pre-locking the target with the missile’s seeker and transmitting the information to the operator, who then issues the launch command,” intelligence noted.

Ukrainian military intelligence emphasizes that the primary goal of this development is to create a threat to the Ukrainian army and tactical aviation, thereby reducing the effectiveness of intercepting enemy UAVs.

Consequently, the multi-purpose version of the Iranian Shahed-136 gains a new role, and the operational experience will likely be shared with Iran and other Russian partners.

This case demonstrates a dangerous trend: authoritarian regimes are combining outdated arsenals with modern electronics, creating asymmetric threats to aviation and global security.

Fighting the “Shaheds” is increasingly not only a Ukrainian task but part of a broader confrontation with a network of authoritarian regimes testing the future of warfare today.

© Valentina Petrova/Associated Press

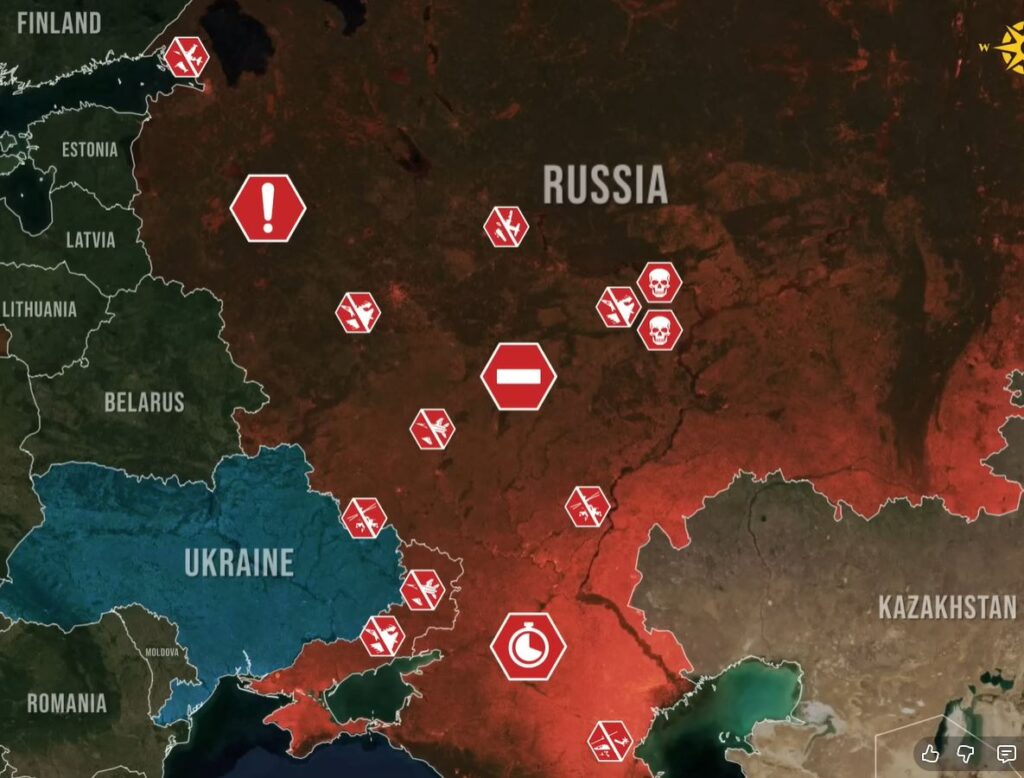

As EU leaders debate using frozen Russian assets to fund Ukraine’s defense, the exact legal mechanism paralyzing that decision is being turned against Ukraine itself. A new report reveals 13 arbitration cases now challenging Kyiv’s sanctions and national security measures—most using European investment treaties.

An analysis by the German NGO PowerShift, published on 9 December, found that sanctioned Russian oligarchs and companies have filed 24 cases directly challenging the sanctions imposed after the 2022 invasion. More than half target Ukraine.

The total claimed exceeds $62 billion—approaching the €70 billion ($82.3 billion) in military assistance the EU has provided since the war began.

Belgium has resisted using €210 billion ($247 billion) in frozen Russian assets partly due to fears of investor-state arbitration under its treaty with Russia. Yet, Ukraine faces even greater exposure: seven cases against Kyiv are based on investment treaties with EU member states, and two more on the UK-Ukraine treaty.

The mechanism—investor-state dispute settlement, or ISDS—lets foreign investors sue governments before private arbitration tribunals rather than national courts. Awards can be enforced against a country’s assets worldwide.

Russian oligarch Mikhail Fridman, who faces EU and UK sanctions over alleged ties to the Kremlin, has filed five ISDS cases and threatened a sixth. Three target Ukraine directly.

After Kyiv nationalized Sense Bank in July 2023—because its owners were under sanctions — Fridman’s Luxembourg-based ABH Holdings filed a $1 billion claim.

The legal basis: the 1996 investment treaty between Ukraine and the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union.

A second Fridman-linked company, CTF Holdings, is suing Ukraine under the same treaty after Kyiv sanctioned it for ties to the oligarch. A third case, filed by EMIS Finance under the Netherlands-Ukraine treaty, demands $400 million in compensation for loans connected to the nationalization of Sense Bank.

Ukraine’s Security Service has accused Fridman of funneling 2 billion rubles (roughly $21 million at 2023 exchange rates) into Russian military factories since the full-scale invasion began. He denies the allegations.

The pace is accelerating. Of 13 ISDS cases against Ukraine’s sanctions and security measures since 2022, six were filed this year.

Russian oil giant Tatneft submitted a notice of dispute against Ukraine after Kyiv sanctioned and froze its assets.

The claim—filed under the Russia-Ukraine investment treaty that Kyiv terminated in 2023—can still proceed due to a 10-year sunset clause protecting existing investments.

Other cases target Ukraine’s sanctions on companies linked to Russian businessmen Vadym Novynskyi and Andrey Molchanov. British-registered Enwell Energy is suing under the UK-Ukraine treaty; German-registered AEROC Investment Deutschland under the Germany-Ukraine treaty.

The EU’s 18th sanctions package, adopted in July, explicitly bars sanctioned Russians from using ISDS to challenge European sanctions and blocks enforcement of any awards. Switzerland adopted similar measures in October.

However, these protections do not extend to Ukraine.

This is a critical gap. European investment treaties are being used to challenge Kyiv’s national security decisions, yet Brussels has offered no equivalent shield. The cases “could have significant impacts on Ukraine’s public budget,” the PowerShift report notes.

The authors recommend that the EU and Ukraine negotiate a termination treaty for all investment agreements between them, following the model EU states used to cancel treaties among themselves. Such termination would also be required if Ukraine joins the EU.

There is no public indication that Brussels or Kyiv is pursuing this. So far, the Ukrainian government has not publicly addressed the growing pattern of ISDS cases targeting its sanctions policy.

This winter, the war will become more tangible, colder, and darker for Russia than it has been before, said Yevhen Dykyi, a former company commander of the Aidar Battalion. At the same time, he warned that this does not mean the winter will be easy for Ukraine, Radio NV reports.

However, the balance of power is shifting significantly, primarily in the areas of drones and energy pressure.

According to Dykyi, the Defense Forces have already succeeded in striking some Russian enterprises involved in drone assembly.

The problem is that Russia has many such facilities, most of which carry out final assembly, while key components are supplied from China. Despite this, Ukraine has gradually managed to level the situation.

Dykyi emphasized that Ukraine and Russia are entering the winter period under fundamentally different conditions.

“This winter will be colder and darker in Russia than it will be for us. But that does not mean it will be easy for us,” he stressed.

He added that Russian society may, for the first time, feel the consequences of the war not through television screens but in everyday life, through problems with energy supply and security deep in the rear.

According to Dykyi, drone warfare has become the key factor driving these changes. This winter, Ukraine is no longer merely catching up but is reaching parity with Russia.

“We are establishing the same kind of combined, comprehensive practice of deployment,” he noted.

Ukrainian drone production has entered a phase of scalability. This is no longer about isolated strikes, but about systematic analytical work, how many hundreds of drones are launched, what percentage is intercepted, and how many targets are hit.

According to him, in terms of both quantity and effectiveness of drones, Ukraine is expected to move this winter from parity to overtaking Russia.

Commenting on expectations within Russian society, Dykyi made an ironic remark.

“They wanted to play this game together, so let’s see how Russian society reacts when the only thing left to keep them warm is love for their leader," he stressed.

He also noted that Ukraine’s missile component for strikes against Russia is still at an early stage. There are not many missiles, and some are still undergoing testing. By contrast, drones have already become a systemic force capable of influencing the course of the war even in winter.

© @ChrisMinnsMP, via X, via Reuters

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

Ukrainian forces struck the Luch combined heat and power plant in Belgorod overnight on 15 December, according to Belgorod Oblast governor Vyacheslav Gladkov, ASTRA, and The Moscow Times.

"Preliminarily, no one was injured," Gladkov claimed, though he confirmed "serious damage to engineering infrastructure."

Windows were damaged in six apartment buildings and one private house.

Local outlet Pepel reported a large plume of smoke rising over the power plant area following the strike. ASTRA geolocated the source of the smoke.

The Luch CHP plant is one of Belgorod's key energy facilities, running on natural gas and supplying electricity and heat to the Kharkovskaya Gora neighborhood and other city districts, according to Russian media.

This marks the fourth attack on Belgorod's energy infrastructure in recent months. On 28 September, Ukrainian forces targeted the Luch plant and a city substation, causing power outages in parts of Belgorod, Stary Oskol, Shebekino, and several other settlements in the region. One of the plant's power units was hit again on 5 October, leaving thousands of residents without electricity. Another strike followed on 10 November.

The overnight operation extended beyond Belgorod. Moscow Mayor Sergei Sobyanin reported from the evening of 14 December through the morning of 15 December about drones allegedly shot down over the Russian capital, claiming a total of 15 drones were destroyed. He mentioned only "falling debris" after the "downings" but provided no information about consequences. Sheremetyevo Airport imposed restrictions under the "carpet" plan, with aircraft arrivals and departures requiring coordination with relevant authorities.

In Rostov Oblast, Governor Yuri Slyusar said drone attacks hit several districts. A car caught fire, a private house roof was damaged, and some buildings had partially damaged windows. He said that damage to power lines in Kamyansk district shut down a water intake facility and pumping station. Residents of the Zavodskoy neighborhood in Kamyansk, Maslovka hamlet, and Pogorelovo station were left without water supply.

Russia's Defense Ministry claimed to have intercepted and destroyed 130 Ukrainian drones overnight. The ministry's breakdown: 38 over Astrakhan Oblast, 25 over Bryansk Oblast, 25 over Moscow Oblast (including 15 headed for Moscow), eight each over Belgorod, Rostov, and Kaluga oblasts, six over Tula Oblast, four over the Republic of Kalmykia, three each over Kursk and Oryol oblasts, one over Ryazan Oblast, and one over the Caspian Sea.

According to Telegram channel Shot, citing Moscow and Moscow Oblast residents, explosions were heard overnight in the Istra district of the capital, as well as in Kolomna and Kashira in Moscow Oblast.

Recent Ukrainian drone operations have intensified. On 11 December, Russia reported attacks on Moscow, Novgorod, and Smolensk regions. On 12 December, Russians claimed an attack on an oil refinery in Yaroslavl and a hit on an apartment building in Tver.

© Odd Andersen/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

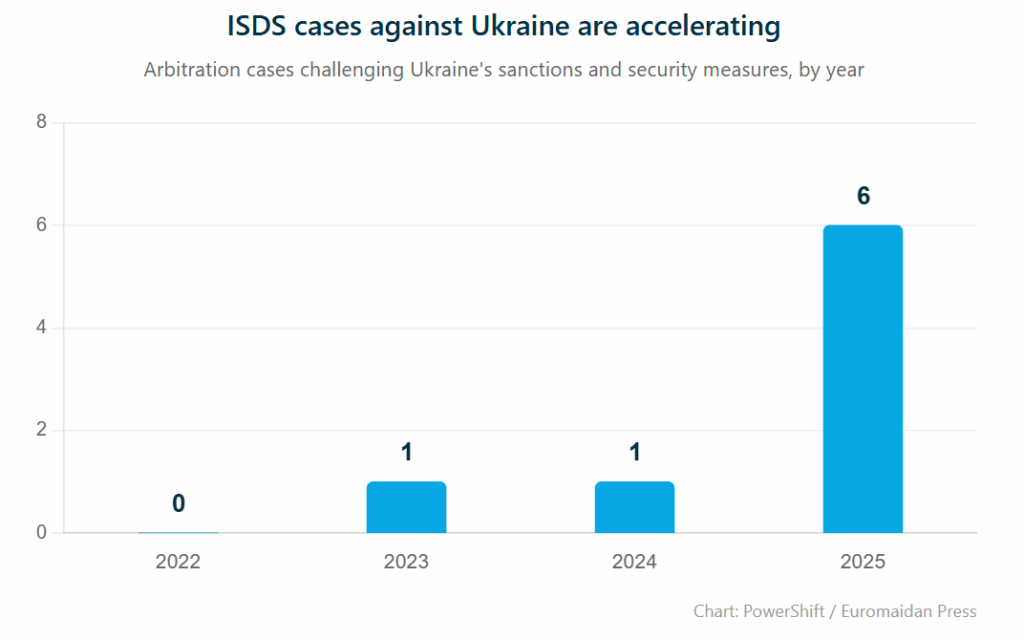

On Friday, the EU made Russian asset freezes permanent—removing the risk that Hungary could veto renewals and force the money back to Moscow. By Monday, the bloc’s top diplomat was admitting the next step is “increasingly difficult.”

EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas told reporters in Brussels that converting frozen Russian assets into loans for Ukraine remains the “most credible” funding option—but member states still can’t agree on how. “The other options are not really flying,” she said.

“We are not there yet, and this is increasingly difficult, but we still have some days.”

Those days are running out. EU leaders will meet on Thursday and Friday to decide whether €210 billion in immobilized Russian sovereign assets can be used to back a loan that would fund Ukraine’s military and civilian needs through 2027. Without an agreement, Europe loses its strongest card in any peace negotiations with Moscow.

Belgium, where most assets sit at the clearinghouse Euroclear, backed the indefinite freeze last week. But Prime Minister Bart De Wever’s government simultaneously called on the Commission to propose alternative funding options—a demand now joined by Malta, Bulgaria, and Italy.

The problem: no alternatives exist.

The previous backup—a €90 billion eurobond scheme—died when Hungary vetoed it on 5 December. Direct funding from national budgets faces even steeper resistance.

Russia is applying pressure of its own. The Bank of Russia filed a lawsuit in Moscow on Monday seeking 18.2 trillion rubles ($229 billion) from Euroclear—the latest in a series of legal actions since 2022 that feed Belgian concerns about liability.

The asset deadlock comes as US-Ukraine peace negotiations resume in Berlin this week with European participation. US envoy Steve Witkoff and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy are both expected.

The Kremlin has already rejected European modifications to Trump’s peace plan as “unacceptable”—and Moscow has accused Chancellor Friedrich Merz of “warmongering” for pushing the frozen assets scheme.

The timing creates a bind.

If Europe can’t agree on using Russian money to fund Ukraine, its influence in shaping any peace deal shrinks. Putin isn’t negotiating seriously because he’s betting Europe will exhaust itself first. A two-year funding package backed by frozen assets would break that bet.

EU leaders have 72 hours to prove him wrong.

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Mario Tama/Getty Images

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Lam Yik Fei for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Delil Souleiman/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© John Moore/Getty Images

© Guido Bergmann/German Government Press Office, via Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Isabella Moore for The New York Times

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times

© Victor J. Blue for The New York Times

© Asanka Ratnayake/Getty Images

© Matthew Abbott for The New York Times