Atrocities in Sudan Require World’s Attention, U.N. Says

© Marwan Ali/Associated Press

© Marwan Ali/Associated Press

© Afif Amireh for The New York Times

© Wagner Meier/Getty Images

© Mohamed Jamal/Reuters

© Pablo Porciuncula/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Jorge Silva/Reuters

© NRC, via Associated Press

© Fabrice Coffrini/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Diego Ibarra Sanchez for The New York Times

© Abbie Townsend for The New York Times

© John Wessels/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Saher Alghorra for The New York Times

© Saher Alghorra for The New York Times

The drone hovered overhead with its camera running. It followed a man as he ran from his house toward shelter. Tracked his movements. Waited. Then struck.

"We are hit every day," the man later told investigators. "Drones fly at any time—morning, evening, day or night, constantly."

That feeling—of being perpetually watched, perpetually hunted—turned out to be Russia's strategy.

Across three oblasts in southern Ukraine throughout 2025, the attacks followed the same method. Drones with cameras. Civilians were tracked as they fled. Strikes timed for maximum terror. Then something that made investigators certain this wasn't random combat: the drones came back.

The same targets hit again. And again.

Ambulances with clear protective markings—vehicles that international law specifically shields from attack—struck multiple times. Fire brigades hit while responding to earlier strikes. Humanitarian distribution points where civilians gathered for aid. Power infrastructure serving hospitals and homes.

The attacks spanned Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk, and Mykolaiv oblasts along the right bank of the Dnipro River—a 300-kilometer stretch of Ukrainian-held territory. The question for investigators was: Was this chaos or coordination?

The Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Ukraine spent months collecting evidence. They gathered roughly 500 videos from the affected regions, verified 247 of them, and interviewed 226 survivors and witnesses.

The evidence showed coordination, centralized command, and systematic methodology designed not to win tactical victories but to empty entire regions of their populations.

On 27 October 2025, the Commission presented its findings to the UN General Assembly's Third Committee with a stark conclusion: this isn't warfare. It's two distinct crimes against humanity.

War crimes and crimes against humanity aren't the same thing. War crimes can be isolated—a commander's decision, a unit's actions, a moment's brutality. Crimes against humanity require something more: a widespread or systematic attack directed against a civilian population. Evidence of policy, not chaos.

The Commission found the policy.

The drone strikes weren't tactical errors or collateral damage from combat. They were designed to spread terror and force civilians from their land—what international law calls "murder and forcible transfer of population." The Commission also documented a second crime: deportations and transfers of civilians from Russian-occupied areas, some subjected to torture.

The distinction matters for one reason: accountability.

International humanitarian law has rules even for war. The Fourth Geneva Convention—recently given updated guidance by the International Committee of the Red Cross—protects ambulances, civilians, and essential infrastructure. It requires good faith interpretation to preserve the law's humanitarian purpose.

Russia's documented pattern—deliberately targeting marked emergency vehicles, using repeat strikes to prevent rescue operations, systematically hunting civilians with drone cameras—represents the opposite of good faith. It's a policy designed to empty the law of meaning while maximizing civilian harm.

The Commission isn't writing history. It's building legal cases. Every verified video, every witness interview, every documented pattern creates evidence that prosecutors can use. The classification as crimes against humanity means Russian commanders can't claim isolated decisions or tactical necessity.

The documentation shows system. And systems have planners.

Russia does not recognize the Commission. It has not granted investigators access to occupied territories. It continues to deny intentionally targeting civilians despite extensive verified evidence showing coordinated attacks across 300 kilometers.

The Commission, established by the UN Human Rights Council on 4 March 2022, has had its mandate extended repeatedly—most recently in April 2025. It must submit a comprehensive report by February-April 2026.

The Commission has previously confirmed that torture and enforced disappearances by Russian authorities also constitute crimes against humanity, building a comprehensive record across multiple categories of international law.

The stakes reach beyond Ukraine. Russia's defense arguments have been consistent: civilian casualties are unintentional collateral damage in legitimate military operations. We don't target civilians.

The UN report systematically dismantles this defense. The cameras on the drones weren't for targeting military positions. They were for tracking civilians. The repeated strikes on ambulances weren't targeting enemy fighters. They were preventing rescue operations. The 300-kilometer pattern wasn't the fog of war. It was a coordinated policy.

This changes calculations for international courts. Individual commanders can't claim they followed isolated combat orders when the documented evidence shows centralized planning. The UN has now created an authoritative, verified record that future prosecutors can use and that other militaries considering similar campaigns must account for.

© Saher Alghorra for The New York Times

© Brendan Hoffman for The New York Times

© Odelyn Joseph/Associated Press

© Nathan Howard for The New York Times

© Piroschka Van De Wouw/Reuters

© Angus Mordant/Reuters

Life for children in Ukraine has become increasingly dangerous and deadly, according to the latest U.N. figures, which show a threefold jump in the number of deaths and injuries among children over the three months ending in May.

From March through May, 222 children were killed or injured, compared to 73 in the preceding three months, according to a press release from the U.N. Humanitarian Aid Organization for Children (UNICEF) on July 4.

The statement noted that "the ongoing use of explosive weapons in populated areas has been particularly deadly and destructive."

"There is no respite from the war for children across Ukraine," UNICEF Regional Director for Europe and Central Asia, Regina De Dominicis, said. "The situation for children is at a critical juncture, as intense attacks continue to not only destroy lives but disrupt every aspect of childhood."

In April alone, UNICEF noted, 97 children were killed or maimed, which was the highest figure that the U.N. has been able to verify since June 2022. Among the attacks in April was a strike on a playground in Kryvyi Rih, which killed nine children.

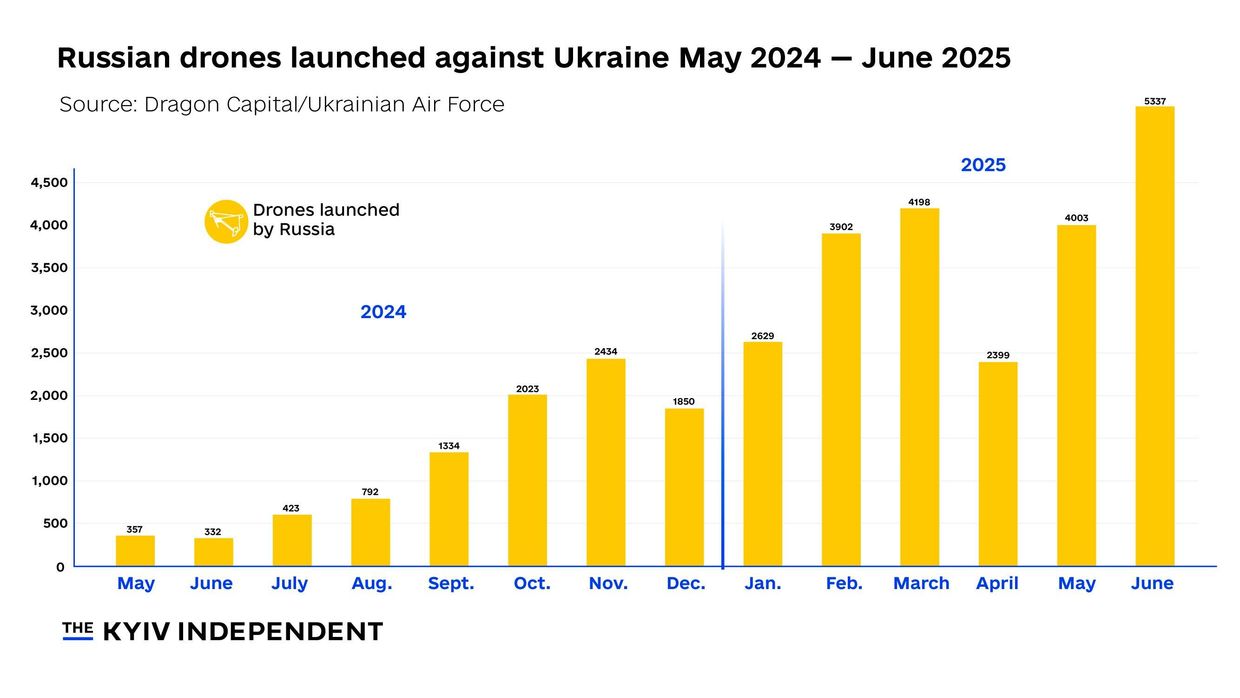

Recent months have seen some of the war's deadliest attacks on civilians, as Russia steps up its aerial strikes on civilian areas and launches record numbers of drones. Russia has dramatically increased its production of these weapons and is now capable of launching in a single night as many drones as it did over an entire month in early summer 2024.

At the same time, the U.S has halted a shipment of weapons that includes air defense missiles, which Ukraine critically needs to defend itself from Russia's attacks.

The Kyiv IndependentThe Kyiv Independent news desk

The Kyiv IndependentThe Kyiv Independent news desk

An internal U.N. analysis has found Russia responsible for a 2022 explosion at Olenivka prison, which killed over 50 Ukrainian prisoners of war (POWs), Ombudsman Dmytro Lubinets said on June 30.

"(A)n internal analysis of the U.N. showed that it was the Russian Federation that planned and carried out the attack," he said in a post to social media.

Lubinets referred to a report by the Center for Human Rights in Armed Conflict, whose website features only the investigation into the Olenivka explosion.

The investigation, published on June 26, reads that an "internal U.N. analysis concluded that it was the Russian Federation who planned and executed the attack," though the U.N. did not publicly acknowledge Russia's responsibility.

Russia has denied being responsible for the attack but prevented efforts by the international community to independently investigate the attack and contaminated evidence at the site, according to a report published by the U.N.

Kyiv has said that days before the July 2022 attack, Russia deliberately put Ukrainian members of the Azov Regiment, who were awaiting a prisoner exchange, in a separate part of the Olenivka prison building that was later destroyed in the explosion.

"The report identifies the weapons and ammunition that the Russian Armed Forces used to kill Ukrainian prisoners of war, and also examines in detail the planning, organization, and execution of the murder," Lubinets said.

The ombudsman noted that the U.N. fact-finding mission on Olenivka was disbanded due to a lack of security guarantees, adding that the mission has previously refused to review evidence provided by Ukraine.

Russia has repeatedly violated international conventions protecting the rights of POWs as it continues to carry out its war against Ukraine.

A Russian military court has convicted 184 Ukrainian POWs captured in Kursk Oblast of acts of terrorism, Mediazona reported on June 25.

The POWs captured in Kursk were charged with carrying out a grave terrorist act by a group of individuals, as outlined by the Russian Criminal Code.

Junior Lieutenant Yevhen Hoch was convicted of allegedly carrying out an act of terrorism by taking part in Ukraine's Kursk Oblast incursion.

The Kyiv IndependentYuliia Taradiuk

The Kyiv IndependentYuliia Taradiuk

Russia's memorandum on a peace proposal is the "best offer Ukraine can get today," Russia's envoy to the United Nations (UN), Vasily Nebenzya, said at a UN Security Council meeting on June 20.

"During the direct Russian-Ukrainian talks that were held, we presented our memorandum on a peaceful settlement. It consists of two parts: conditions for a comprehensive long-term peace and conditions for a ceasefire," Nebenzya said.

"This is the best offer Ukraine can get today. We advise accepting it as things will only get worse for Kyiv, from here on out," he said.

At Istanbul peace talks on June 2, Russian negotiators told the Ukrainian delegation that their so-called "peace memorandum" is an ultimatum Kyiv cannot accept, President Volodymyr Zelensky said in an interview published on June 10.

"They even told our delegation: we know that our memorandum is an ultimatum, and you will not accept it," Zelensky said. "Thus, the question is not the quality of the Istanbul format, but what to do about the Russians' lies."

"In Istanbul, we also agreed on a large-scale exchange of prisoners of war," Nebenzya said at the UN Security Council meeting on Ukraine.

Aside from agreeing on large-scale prisoner exchanges, peace negotiations between Ukraine and Russia have been largely inconclusive as Moscow continues to issue maximalist demands toward Kyiv.

Nebenzya noted that Ukraine and Russia should resume direct peace talks in Turkey after June 22, despite Russia's intensified drone and missile attacks on Ukraine.

On June 17, a Russian drone and missile attack on Kyiv killed 30 people and injured another 172. The nearly nine-hour-long strike saw Moscow's forces launch large numbers of drones and missiles at Ukraine's capital.

Russia's statements diverged from those of other speakers at the UN Security Council meeting on June 20.

"We call on Russia to agree to an unconditional ceasefire. Russia initiated this war; we call on Russia to end it," Barbara Woodward, the U.K.'s Permanent Representative to the UN, said.

Russia has illegally laid claim to five Ukrainian regions despite not controlling all of the territory. The regions include Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson oblasts, as well as the Autonomous Republic of Crimea.

The Kyiv IndependentKateryna Hodunova

The Kyiv IndependentKateryna Hodunova