Ukraine has taught the rest of Europe a lesson in what innovation is, and what it isn't.

Gripped in the teeth of Russian aggression, Ukraine has harnessed engineers just out of university to develop next-gen drones, produced them at scale at the lowest possible cost, tested them in the field, refined them according to frontline feedback, and then repeated the process.

Thanks to this ultra-modern approach to arms development and procurement, cheap, lethal, and increasingly sophisticated drones, which are able to keep pace or beat Russian countermeasures, have been streaming out of Ukrainian factories.

Compare this to what's happening in the European NATO member states. Defense budgets are growing, but procurement officers favor the big primes. These companies have big reputations, well-paid lobbyists, and direct lines to the right people. They receive lucrative contracts to develop platforms that take years to fulfill.

Start-ups and smaller companies, exactly those best placed to innovate, are largely ignored. They often go unnoticed altogether.

Europe's drone wall faces reality check

These differing approaches to innovation matter. Last month, it was widely reported that the NATO member states would move forward with their plans to build a "drone wall" along the eastern flank of Europe.

It would, in theory, be made up of a giant system of drones working together to create a defensive screen. These drones would fly in patrols, be linked by sensors, and be able to track and intercept threats.

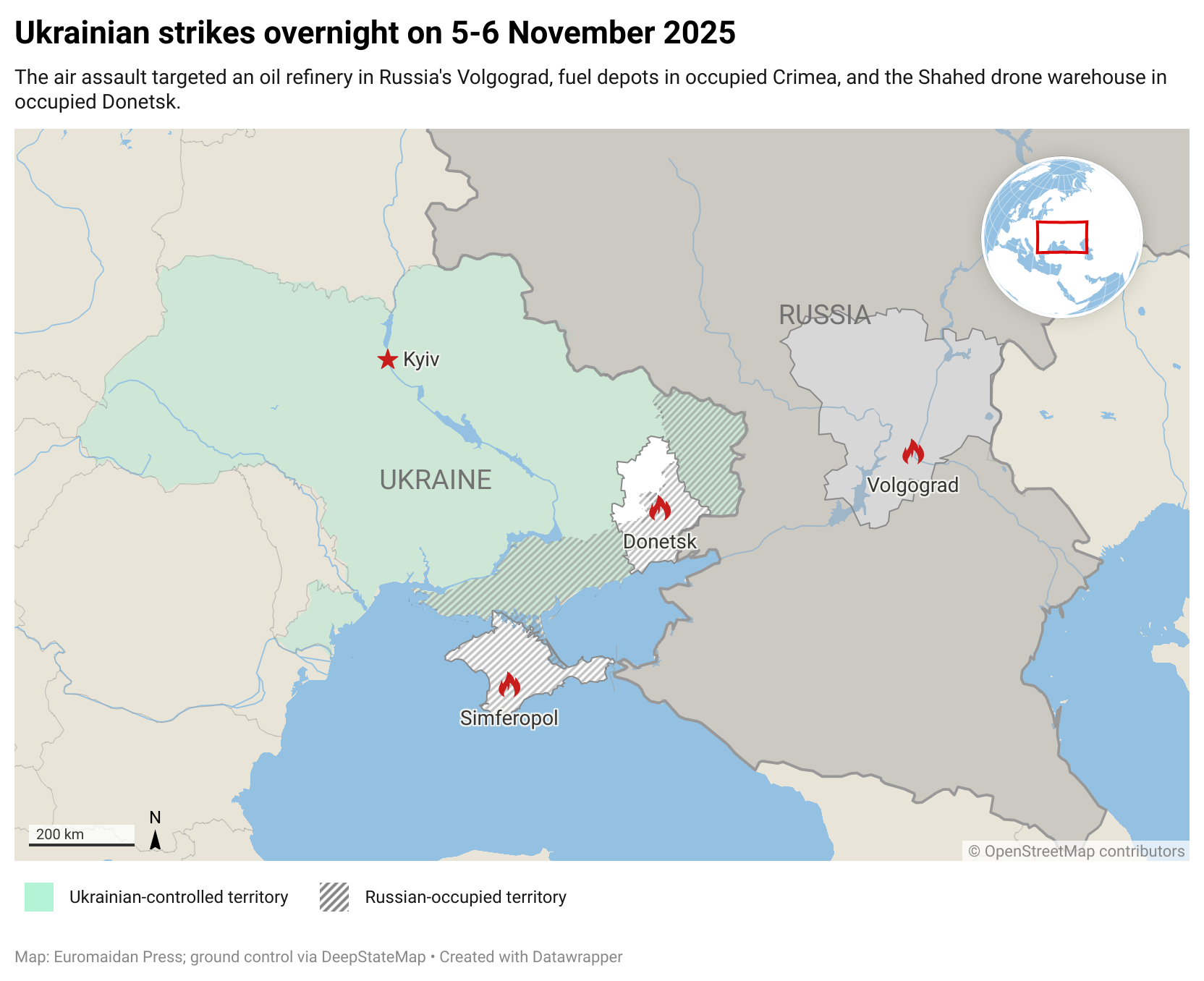

Plans have been expedited because Russia has been testing the waters outside of Ukraine. Poland shot down Russian drones that had entered its airspace. Denmark has been forced to buy anti-drone equipment. Romania said it found "new drone fragments" near its border with Ukraine.

Breaking free from Chinese supply chains

To build a drone wall, Europe will need to find a way to wean itself off Chinese materials. Much of the software and hardware used in drones comes from China, which makes NATO dependent on supply chains that are largely controlled by a major non-NATO power.

Explore further

Ukraine already built Europe’s “drone wall”—here’s how it actually works

It's revealing that the US has been thinking about relaxing its decades-old controls on exporting certain American technology to its allies. Washington has historically limited the number of external operators allowed to use drones like the advanced MQ-9 Reaper.

But it now sees that expanding sales of MQ-9s and other technology would have the twin effects of increasing interoperability with partners and of blocking out China and others from exploiting a gap in the market.

In short: the White House doesn't want NATO reliant on and strengthening its biggest rival, particularly by buying equipment critical to modern warfare.

This isn't the only issue, however. Talk of a "drone wall" betrays a lack of understanding about the nature of modern warfare.

Why a wall won't work

This is no longer the year 122 CE, when Roman Emperor Hadrian built a wall in the north of England separating the so-called civilized world and the unconquered barbarian wilderness. You can't simply put up a wall of drones between Eastern Europe and Russia, and so block Russian forces from getting into the rest of Europe.

Drones can appear anywhere, at any time. You can hide them in a truck, on a boat, or in a submarine. You can drop them out of space. Even if this "wall" is made up of a state-of-the-art drone fleet, an attacker can completely bypass it and release their drones thousands of miles away, near critical infrastructure.

This is why Europe needs something like a drone dome: an integrated solution that includes connected drones, as well as passive systems, and countermeasures. That will take time, which is why Europe should start by shielding the most vital infrastructure and then, as drone production accelerates, protect other assets.

How Europe can learn from Ukraine

But Europe's main challenge is the drone technology itself. Drone countermeasures are becoming increasingly sophisticated. The vast majority of even state-of-the-art drones are intercepted, and a well-timed electromagnetic pulse can down a whole swarm.

The drone wall on the Eastern flank has to be made up of cutting-edge drones, with the best software and hardware, shielded with the latest, EMI-resistant advanced materials.

That requires, in turn, a truly modern approach to innovation and procurement that draws on the Ukrainian model and puts energy, ambition, expediency, and creative freedom above historic defense relationships and big, headline-grabbing platform procurement deals.

Neither this, nor the suggestion that Europe needs to inculcate a Ukraine-inspired culture of innovation, are unreasonable or unrealistic demands. The European NATO member states have the money, the research institutions, the intelligence, the innovation culture, and the talent to build a world-class, indeed world-leading defensive drone system.

Explore further

From shared threats to shared tech—EU needs Ukraine’s secrets to power its “drone wall”

And, as Ukrainians know all too well, conflict isn't something that happens "somewhere else." Poland, Denmark, Norway, and Romania have complained that Russia is probing at their defenses. The former head of Britain's MI5 said only recently that she believes the UK may already be at war with Russia.

The urgency of now

There's no time to lose. What is unreasonable, as well as unrealistic, is thinking that hostile actors will wait for Europe to wake up to the threat, or that without a concerted, sustained, urgent effort, Europe will rearm in the way that it needs.

EU Defense Commissioner Andrius Kubilius thinks a drone wall could be built in a year. Evika Siliņa, Latvia's prime minister, told reporters she thinks it could be "doable" within a year to a year-and-a-half. German defense minister Boris Pistorius says it will take more than three or four years. Though EU leaders in general have given the idea "broad support," there are clearly disagreements to iron out.

But what we need is a dome, not a wall, and we need it to be in place quickly. To policymakers and opinion-formers: we need you to act before our enemies take the ability to act away from us.

Robert Brüll is the CEO of FibreCoat, an advanced materials technology company which develops ultra-resistant fibers and coatings used in dummy tanks, decoy ships, spacecraft, and chaff for fighter jets.

Editor's note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press' editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

The General Staff

The General Staff

Exilenova+, Supernova+, Russian media

Exilenova+, Supernova+, Russian media