Ukrainian writer Zhadan: “Once war ends, it will continue in culture”

© Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved

© ASSOCIATED PRESS

Exxon Mobil CEO Darren Woods says that the oil giant has no plans to return to Russia. However, the company is negotiating with Russian officials over the recovery of $4.6 billion in expropriated assets, the Financial Times reports.

Russian officials continue to claim that Exxon “may be allowed” to return to the country amid the Alaska peace summit, at which “normalization and deepening of economic ties” between Russia and the US were discussed.

Exxon Mobil exited the Sakhalin-1 oil project in March 2022, following Russia’s all-out war on Ukraine.

Despite wanting to reclaim its assets, Russian authorities denied the request. In October 2022, President Vladimir Putin signed a decree ordering the forced seizure of Exxon’s stake, transferring it to the Russian company Rosneft through its subsidiary.

Exxon was forced to write off assets worth over $4.6 billion, having effectively lost control of its stake in the project and being unable to operate or extract value from it.

Ahead of the meeting with Trump, Putin signed a decree that potentially allows foreign investors, including Exxon Mobil, to reclaim their shares in the project.

However, according to CEO Darren Woods, Exxon has no intention of returning to Russia.

“We don’t have any plans to re-enter Russia. This was really around settlement discussions around the arbitration associated with the expropriation of our assets in 2022,” Exxon’s top executive said.

He added that Exxon executives are negotiating with Russian officials about recovering the $4.6 billion in expropriated assets, but not about investing in the country.

Russian officials continue to say that Exxon “may be allowed” to return, amid the Alaska peace summit, which discussed the normalization and deepening of economic ties between the US and Russia.

On Wednesday, Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Sergey Ryabkov stated that negotiations between investment envoy Kirill Dmitriev and US officials “continue regarding cooperation in energy deals, including Sakhalin-1.”

The longer Russia prolongs its war in Ukraine, the more the global balance of power shifts. Recently, Moscow reportedly supplied North Korea with nuclear submarine modules, including a reactor, a move that could mark a breakthrough for Pyongyang in building its own strategic submarines, Korea JoongAng Daily reports, citing South Korean government sources.

Russia and North Korea are ideological allies, united by their opposition to Western dominance. The partnership has deepened: Pyongyang provides ammunition, ballistic missiles, and personnel for Russia’s war in Ukraine, while in return, it is believed to be receiving technologies that could one day threaten the West.

According to several officials, during the first half of 2025, Russia may have delivered two or three modules to North Korea, including a reactor, turbine, and cooling system, which are the key components of a nuclear submarine’s power plant. These were not newly produced units but parts removed from decommissioned Russian submarines.

“Since last year, North Korea has been persistently requesting nuclear submarine technology and advanced fighter jets from Russia.

Russia was initially reluctant but appears to have agreed to provide them this year,” one government source said on condition of anonymity.

For Pyongyang, nuclear-powered submarines are a strategic priority, as they could enable the capability to launch nuclear strikes against the US. In March, the state-run Rodong Sinmun published photos of Kim Jong Un inspecting a nuclear submarine under construction.

Until recently, experts were convinced that North Korea could not independently develop a reactor for submarines. If the transfer of modules is confirmed, the country would gain access for the first time to a technology that had been out of reach.

Reports also suggest Pyongyang demanded this assistance from Moscow in exchange for sending troops to support Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Confirmation of the transfer would mean Russia has crossed a “red line,” in blatant violation of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). Such a step would likely provoke new sanctions targeting both North Korea and Russia.

South Korea’s intelligence service has already passed the information to the US and its allies.

Ukrainian public broadcaster Suspilne reports that intelligence data show about 20,000 Cubans are fighting on Russia’s side in the war against Ukraine. The report was discussed during a US Congress security briefing, which highlighted Cuba’s role in aiding Russia both with fighters and sanction evasion.

On 18 September, US Representative Mario Díaz-Balart, a Republican from Florida, hosted a virtual national security briefing with Ukrainian officials and US lawmakers. The focus was the “alarming presence of thousands of Cuban regime troops fighting alongside Russia in the war against Ukraine” and the threat this poses to US and regional security.

Florida representatives María Elvira Salazar and Carlos Giménez also participated, alongside Cuban opposition figures and Ukrainian officials including presidential sanctions adviser Vladyslav Vlasiuk, intelligence representative Andrii Yusov, and members of parliament Oleksandr Merezhko and Marian Zablotskyi.

According to Suspilne, Ukrainian intelligence representative said at the meeting that around 20,000 Cubans have been recruited by Russia. About 1,000 signed formal contracts with Russia in 2023–2025. The average age of these mercenaries is 35.

Ukrainian officials presented a list of 39 confirmed Cuban fatalities but stressed that the figure represents only part of the actual losses. Each Cuban fighter reportedly receives about $2,000 a month. Yusov noted that while the payment is small, it is “a powerful argument” for Cuba’s impoverished population.

Briefing participants also stressed how Russia continues to bypass sanctions with support from Cuba, China, Iran, and North Korea. According to intelligence data, critical microchips and other components flow into Russia’s defense industry through these countries. Officials stated that 60% of Russia’s artillery shells come from North Korea, while Iranian drones are used in major strikes against Ukrainian infrastructure. Ukrainian intelligence emphasized that Cuban fighters form the second-largest foreign mercenary group in Russia’s ranks.

Suspilne Krym earlier reported that Cuban mercenaries, alongside recruits from African states and other Russian allies, undergo training in Russian-occupied Crimea before being deployed to fight against Ukraine.

There was a time, not too long ago, when the T-64BM Bulat was Ukraine’s most modern tank. But times have changed. And now the survivors of the 100 pre-war Bulats have trickled down to some of Ukraine’s least active brigades.

The fate of the surviving Bulats speaks to the Ukrainian tank corps’ huge leap in capability in just the 43 months since Russia widened its war on Ukraine. But it also speaks to a shortage of working tanks in the Ukrainian inventory as Ukraine’s roughly 130 ground combat brigades reorganize into a new corps structure, with multiple brigades—each with thousands of troops and potentially dozens of tanks—under a single command.

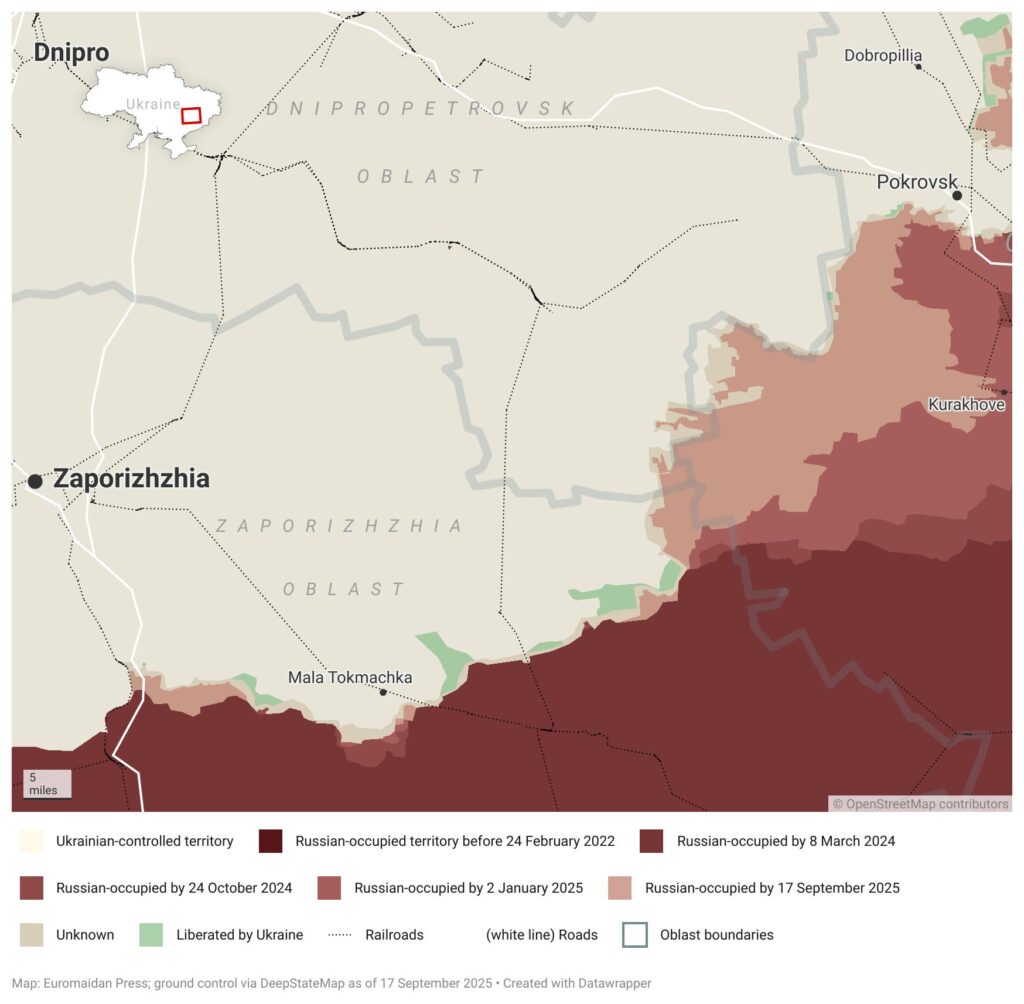

A photo that circulated online recently depicts a war-weary Bulat in training with the 118th Territorial Defense Brigade. The brigade is holding the line outside Mala Tokmachka in southern Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia Oblast, a comparatively quiet sector despite a few recent Russian assaults.

The 49-ton, three-person T-64BM was, until recently, the ultimate T-64—and the best tank in the Ukrainian inventory. The Ukrainian army went to war in 2022 with around 100 Bulats, many if not most of them in service with the elite 1st Tank Brigade.

Two years later, the 1st Tank Brigade had switched to the latest T-64BV, which is several tons lighter than the T-64BM and has newer and much better optics. The 70 or remaining Bulats—a couple dozen have been lost in action—apparently cascaded to the 109th and 118th Territorial Brigades.

The switch makes sense. When the Malyshev tank factory in Kharkiv designed the Bulat back in the 1990s, it added features such as improved armor and fire controls, but didn’t add enough engine horsepower to compensate for the resulting extra weight. “It proved too heavy,” one expert wrote about the Bulat. “There were also problems with air intake and filters.”

There’s some speculation that the Bulats are also badly in need of an overhaul. In any event, by 2025, the Bulat would no longer be Ukraine’s best tank. Ukraine’s super-upgraded T-64BVs have been joined by ex-German Leopard 2s and ex-American M-1s, among other tanks.

Territorial brigades tend to be less well-equipped than army, air assault, marine, and assault brigades and tend to fight defensively rather than lead offensive operations.

So it should come as no surprise that, for example, the assault branch’s 425th Assault Regiment operates American-made M-1s donated by Australia, but the territorials operate overweight, underpowered Bulats and ex-Croatian M-84s based on downgraded Soviet-made T-72Ms.

The Bulats are probably adequate for brigades that aren’t expected to use their tanks especially aggressively. Ideally, the territorials would operate the same tanks as the other ground combat branches. At present, that’s not really an option.

Ukraine had around 1,000 tanks when Russia widened the war in February 2022. In 43 months of hard fighting, the Ukrainians have lost around 1,000 tanks but have gotten another 1,000 tanks from their foreign allies. Wear and tear has removed hundreds of otherwise intact tanks from the active rolls, however.

Bottom line: Ukraine is low on tanks.

The ground forces’ reorganization into an 18-corps structure hasn’t solved the problem. As part of the reorganization, all five army tank brigades plus 13 other brigades—including several territorial brigades—are transforming into heavy mechanized brigades, one for each corps.

Each heavy mech brigade should have two tank battalions together operating around 60 tanks. That’s fewer tanks than were in the old tank brigades, but more tanks than were in old territorial or mechanized brigades.

The corps reorg hasn’t decreased overall demand for tanks, which Ukrainian formations count on to help compensate for a force-wide shortage of trained infantry.

The Bulats might be too heavy and too tired to lead Ukraine’s armored counterattacks. But they’re better than nothing for a couple of territorial brigades.

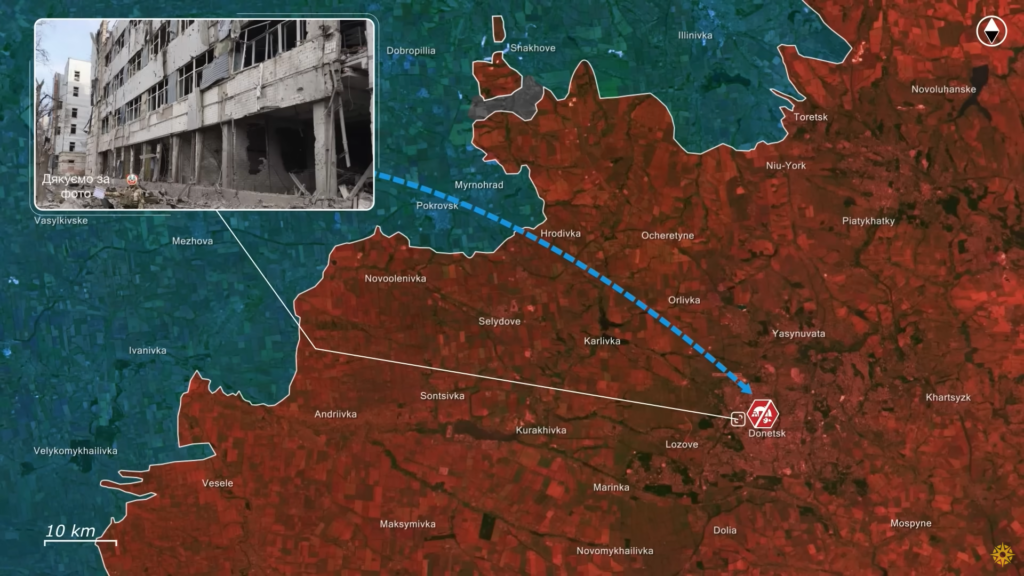

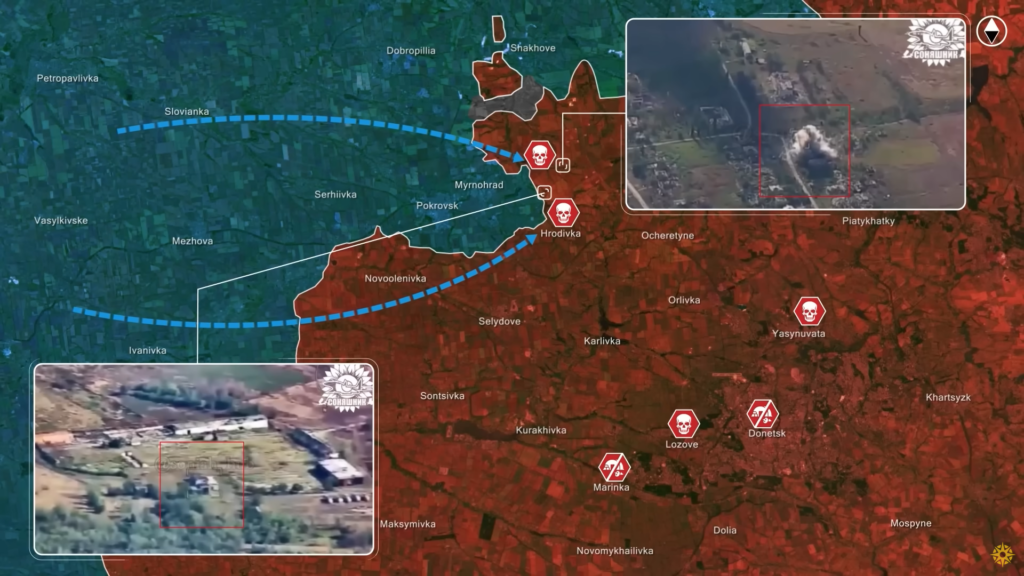

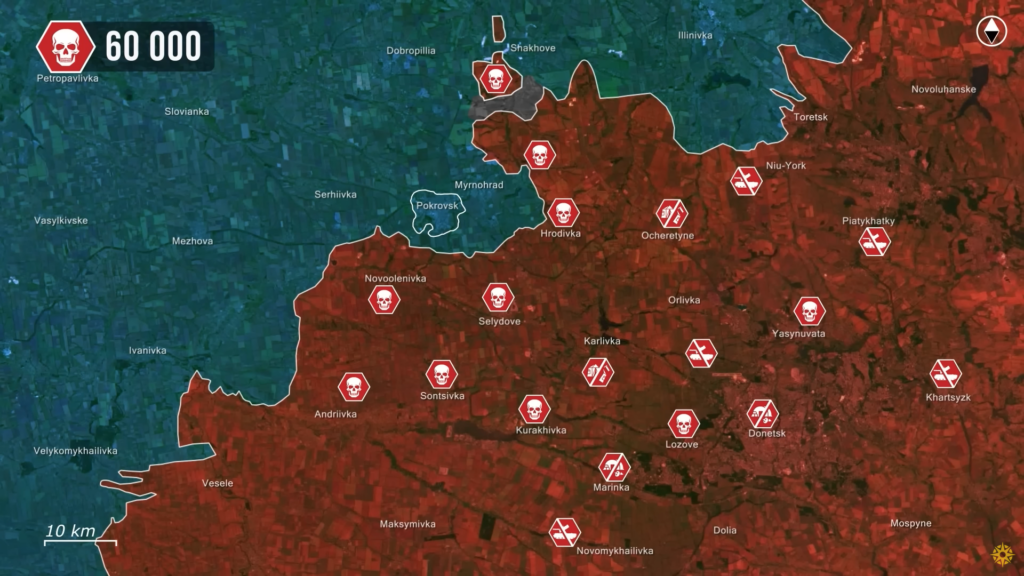

Today there are interesting updates from the Pokrovsk direction.

Here Ukrainian forces have launched a sweeping strike campaign targeting Russian bases, training camps and troop concentrations across the whole Donbas front to bleed out Russia’s capacity for a renewed offensive.

Coupled with the ground operations, these combined efforts have already inflicted 60,000 losses on the 110,000 strong initial Russian grouping since the start of the Pokrovsk offensive.

A repeated Ukrainian strike came in the aftermath of one of the most significant blows against the Topaz plant in Donetsk, which housed a Russian command post.

Eyewitnesses reported again thick smoke, multiple explosions, and noticeable damage to repair and logistics facilities.

Meanwhile, other strikes in Donetsk have repeatedly hit troop concentrations, energy and command infrastructure, preventing the Russians from regrouping smoothly or re-establishing staging areas, as well as the Russian army. The strike was confirmed by multiple released videos from the region.

Closer to the frontline near Myrnohrad, Russian forces concentrations were also targeted by the Ukrainians.

In one geolocated video, a MiG-29 dropped a GBU-62 JDAM bomb on a cluster of Russian assault troops along with the nearby ammunition storage, obliterating both the fighters and their supplies simultaneously.

In another strike, a similar precision weapon demolished a building sheltering an enemy assault group, cutting off the Russian operation before it really started.

Such strikes have undercut the Russian ability to mass troops or prepare joint assaults threatening Pokrovsk.

Essential strikes against Russian air defenses that are conducted in parallel with every radar or air defense system destroyed, meaning fewer obstacles for Ukrainian drones, missile launches and fighter jets to reach high-value targets.

For example, a Zupark radar near Donetsk was destroyed after a shark-reconnaissance drone, followed by a HIMARS artillery strike. Two Pantsir-S1 systems were eliminated within 24 hours, one via a Ram-2X drone strike, the other in Snizhne by another still-unidentified Ukrainian drone, removing critical mobile air defense cover.

Near Donetsk, an expensive Russian Buk-M2 system, costing more than 10 million US dollars, was geolocated and knocked out by HIMARS, as visible on a video published by a Ukrainian blog.

Another Buk-M1 was first tracked to a warehouse by a drone and targeted there unsuccessfully. But when Russian crews attempted to move it, Ukrainian operators readjusted their fire and destroyed it in the follow-up strike.

These Ukrainian strikes have contributed to exceptional Russian losses in the Pokrovsk direction in the past ten months, while the Russian command repeatedly tried outflanking maneuvers, infiltrations and direct assaults aiming to capture Pokrovsk and sever its supply routes.

Ukrainian analysts estimate that Russia has already lost around 60,000 soldiers, killed and wounded during the Pokrovsk offensive alone. The daily toll on Russian manpower and equipment has surged, particularly since the Russian breakthrough near Dobropillia failed and Ukrainian forces began isolating, cutting off and eliminating trapped enemy units.

In addition, Ukrainian air raids against troop concentrations and training camps in the rear have taken out Russian units before they ever reached the front line, reducing pressure on defenders and allowing Ukraine to repel assaults more efficiently, while the combined long-lasting strike campaign has added thousands of Russian losses to the statistic.

Ukraine is executing a well-synchronized multi-layer campaign to first suppress Russian air defense, then strike command posts and logistical nodes, and finally funnel damage onto Russian forces in the rear or awaiting deployment.

Because of these efforts, Russian attempts to mount large-scale assaults have been repeatedly delayed or cancelled, as commanders suffer from the loss of staging bases, supply depots, repair facilities and associated personnel.

The heavy targeting of their command structure has left whole units and even divisions with confusing orders, disrupted communications and fewer operational reserves.

Overall, Ukraine’s recent strikes on bases, training camps and air defense systems represent more than tactical successes.

Strategically decisive in blunting and, in many cases, halting, Russian plans to renew the offensive toward Pokrovsk. By striking rear areas and infrastructure and by destroying air defenses that shield those targets, Ukraine not only protects its front line but sets conditions, where Russian forces must operate exposed and fragmented.

This gives Ukraine breathing room on multiple flanks, reduces incoming pressure, reduces attack speed, and forces the enemy to defend inside and out of the flank.

To and raises the cost of any renewed Russian attack to levels that may not be sustainable, no matter how many additional units the Russian command transfers to this sector.

The fighting around the fortress city of Pokrovsk in eastern Ukraine’s Donetsk Oblast is so fluid and chaotic that the best outside observers—independent analysts and mappers—struggle to make sense of it.

We know a big battle is coming. Potentially “the largest battle of the entire war,” according to American analyst Andrew Perpetua. But the smaller clashes leading up to that likely battle are an ominous sign. When the final battle for Pokrovsk eventually begins, it could defy conventional understanding.

Two leading mappers—Deep State and Unit Observer—have tried to pinpoint the locations of the main Russian and Ukrainian units, as well as the geographic zones of control across a 12-km front stretching from Rodynske to Dobropillia just northeast of Pokrovsk.

— Unit Observer (@WarUnitObserver) September 15, 2025

Dobropillya Direction

Due to Ukrainian reinforcements arriving from Sumy and counterattacks by assault units, Russia redeployed elements of the 8th Army to prevent the semi-encirclement of 51st Army units, which continue their attacks in the Rodynske–Dobropillya direction. pic.twitter.com/J3vkwOETKy

Their maps don’t match. “The situation there is a total mess,” analyst Moklasen observed.

This much we know. In late July or early August, the Russian 132nd Motor Rifle Brigade slipped right past Ukrainian trenches east of Rodynske and marched on Dobropillia, which sits astride one of the two main supply lines into Pokrovsk.

The Ukrainian 1st Azov Corps raced toward the breach. In the weeks that followed, the corps may have mostly destroyed the 132nd Motor Rifle Brigade and carved up the Russian salient. Ukrainian forces “possess the initiative here,” the Ukrainian Center for Defense Strategies reported.

But how many Russians remain in the salient, and where, is unclear.

This uncertainty is becoming the new normal in Ukraine as both sides struggle to recruit enough good infantry and tiny explosive drones increasingly dominate the landscape.

Armored vehicles are too easy to spot from the air, so infantry from both sides tend to attack on foot, hoping to sneak unnoticed across a largely empty no-man’s-land that grows wider by the month as more and better drones range farther and farther.

“With manpower shortages and infiltration tactics, the front line in some areas has become far less defined and certain,” explained Tatarigami, the founder of the Ukrainian Frontelligence Insight analysis group.

“It has reached the point where even soldiers on both sides are uncertain about the front line—at least beyond their own unit’s tactical area,” Tatarigami added. “As a result, sources once considered reliable for mappers are no longer as dependable.”

The chaos afflicts the troops on the ground. In May 2024, a squad from the Ukrainian 3rd Assault Brigade captured a Russian radio during a bitter skirmish over a Russian-held gully somewhere north of Kharkiv in northeastern Ukraine. “We will now try to fuck them over,” the Ukrainian infantry leader said in the official video depicting the fight. “Who is a Russian-speaker?”

A Russian-speaking Ukrainian soldier hopped on the captured radio. “We’re 1st Company,” he transmitted—part of the same battalion as the Russians in the gully. The Russians shifted their fire to avoid hitting their “allies.”

“Let’s go,” the 3rd Assault Brigade infantry leader ordered. “Yell in Russian!”

By the time the Russians realized the soldiers approaching them weren’t actually allies, it was too late. They were all but surrounded.

Help us tell the stories that need to be heard. YOUR SUPPORT = OUR VOICEThat kind of battlefield confusion is becoming more common—and deadlier. Consider the trooper from the Ukrainian 425th Assault Regiment who recently posed as Russian, fell in with two Russian soldiers east of Pokrovsk—and then gunned them down from a few feet away.

For the 150,000 Russians and 50,000 or more Ukrainian troops currently massing around Pokrovsk, these cases of mistaken identity, and the bewildering action northeast of the city, may be previews of much wider chaos as entire field armies and corps clash in the coming weeks.

The battle is probably unavoidable at this point. “Russia has been moving forces into position in Pokrovsk for weeks/months,” Perpetua explained. “They are preparing for what could end up being the largest battle of the entire war.”

“You should not misread what is going on,” Perpetua stressed. But accurately reading the battle, once it commences, could be difficult.

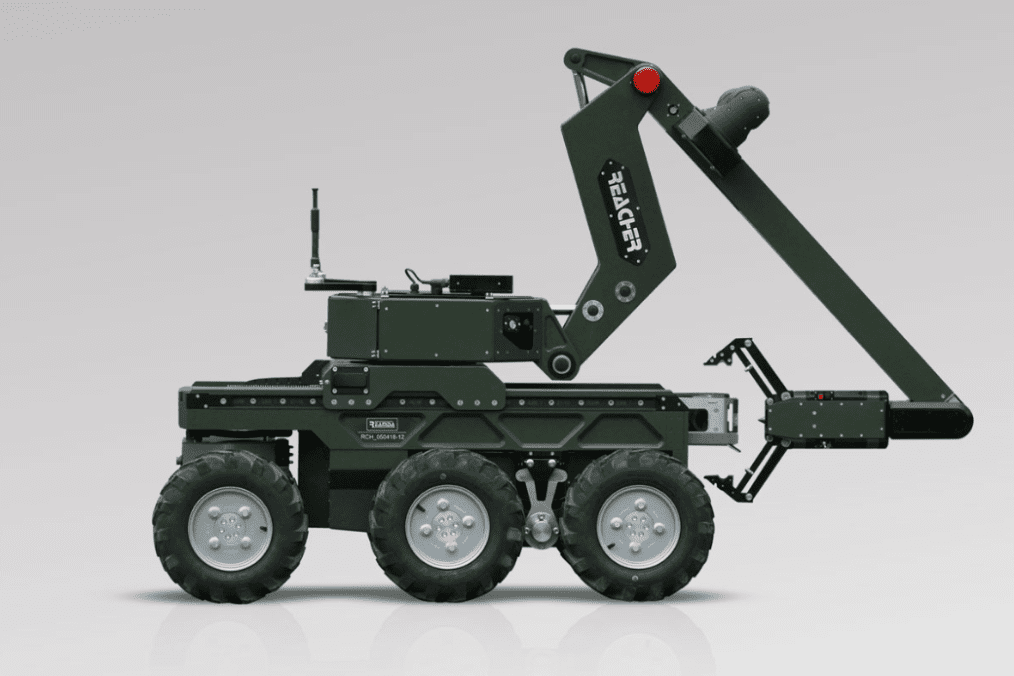

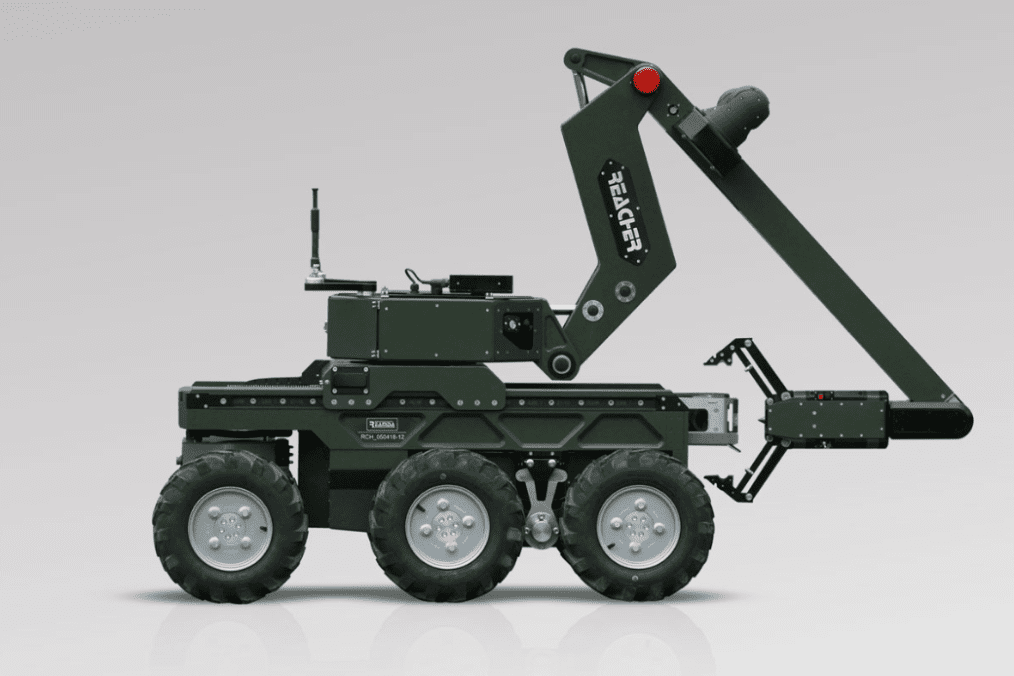

Ireland has delivered 34 military vehicles and three demining robots for Ukraine as part of its non-lethal military aid. The announcement was made on 18 September by the Irish Defense Minister.

According to the Irish Government’s press release, two convoys organized by the Irish Defense Forces have arrived in Poland carrying 34 military vehicles destined for the Ukrainian Armed Forces. The shipments were carried out under Operation Carousel 3, led by the Defense Forces Transport Corps.

The equipment was delivered to the International Donor Coordination Cell in Rzeszów and will be officially handed over in coordination with the Ukrainian military.

The Tánaiste (Ireland’s second-ranking government official) and Minister for Defense Simon Harris said,

“This important donation is a further indication of Ireland’s steadfast support for Ukraine in the face of Russia’s brutal invasion.”

He stressed the need to continue backing Ukraine in the face of ongoing Russian aggression, calling the delivery a “practical example” of non-lethal aid provided since the 2022 full-scale invasion.

The convoy included two Ford Transit vans, three Mercedes ambulances, five Scania 8×8 DROPS trucks, eight 15-seater Ford Transit minibuses, and sixteen double cab Ford Rangers. In addition, three Reacher Robots were delivered to support demining operations as part of a multinational coalition.

The donation supports the Ukraine Defense Contact Group, a coalition of 57 countries and the European Union that delivers military equipment and assistance to Ukraine. Ireland contributes to two non-lethal sub-coalitions under this group: a demining capability coalition co-led by Lithuania and Iceland, and an IT coalition co-led by Estonia and Luxembourg.

Russia is protecting occupied Crimea better than its oil refineries. Moscow is constantly boosting air defense systems in the peninsula with the most advanced systems in response to Ukraine’s strikes, says Ukrainian Navy Spokesperson Captain 3rd Rank Dmytro Pletenchuk, Espreso reports.

Meanwhile, Russian oil remains a key source of revenue that funds its military aggression against Ukraine. In 2025, profits from the oil and gas sector account for about 77.7% of Russia’s federal budget.

“All the air defense systems they have were already deployed there. They’ve concentrated the S-500 ‘Prometey’ in Crimea for a long time,” Pletenchuk says.

The S-500 is Russia’s newest generation air defense system, designed to intercept ballistic and cruise missiles, strategic aircraft, and hypersonic missiles. It can detect targets up to 800 km away and strike them at a range of 600 km, as per Defence Blog.

Equipped with advanced electronic warfare capabilities, it can operate independently or integrate with S-400 systems, each valued at approximately $600 million.

Despite these defenses, Ukrainian forces destroyed an S-500 complex in Donbas this summer with ATACMS missiles, according to the Tivaz artillery division.

Pletenchuk notes that Crimea continues to be a critical location for Russia.

“The Russians will cling to the peninsula until the very end. They are strengthening Crimea’s air defenses far more than their own oil refineries,” he said.

Despite the saturation of air defenses, Ukraine continues to strike Russian military assets in Crimea.

“Our Armed Forces are still able to target key enemy resources. For Russia, the oil industry is particularly important because it funds their operations and contributes to their budget,” Pletenchuk adds.

In August, Ukraine’s Defense Intelligence reported that it destroyed several high-value Russian targets in Crimea, including:

The most interesting of them is the radio telescope. It was built during Soviet times to monitor satellite constellations. Pletenchuk emphasized that “it was genuinely one-of-a-kind.”

A fragment of a Russian military drone Gerbera washed up on a beach in Latvia’s Ventspils district on 18 September, drawing a response from the country’s armed forces and prompting renewed attention to Russia’s unmanned aircraft activity near NATO borders.

The Gerbera drone features a cheap lightweight styrofoam-based fuselage, allowing for easy transport and rapid launch. Russia began actively deploying the model in 2024. During its regular air attacks on Ukraine, Russia uses dozens of Gerberas alongside Iranian-designed Shaheds to overwhelm Ukrainian air defenses. Shahed drones are capable of carrying up to 90 kg of explosives. While primarily intended as decoys, Gerberas have been modified to carry small explosive charges and onboard cameras, enabling them to transmit visual data from inside Ukraine.

The National Armed Forces of Latvia (NBS) reported that a tail section of a drone was discovered on a beach in Vārve parish, Ventspils district. Authorities said it was washed in from the Baltic Sea.

Sargs says Latvia’s State Police said initial information showed no threat had been identified at the site. Nonetheless, NBS dispatched an unexploded ordnance disposal team to analyze the wreckage and determine next steps.

“Such cases are not uncommon along the Latvian coast – remnants of munitions or fragments of other military objects are regularly found washed ashore,” Sargs noted.

Ukrainian defense outlet Militarnyi noted that the wreckage was preliminarily identified as part of a Russian Gerbera drone. This model is actively used by Russia in its war against Ukraine and in provocations targeting NATO countries.

In July, the first confirmed flights of Gerbera drones into the airspace of Baltic countries were recorded. These incidents reportedly caused serious concern among Lithuanian military and government officials.

The same type of drone was previously discovered in Lithuania in early August, having entered from Belarusian territory.

On 10 September, Russia launched a mass incursion of Russian drones into Polish airspace, further confirming the growing threat along NATO’s eastern flank.

On 13 September, a Russian drone violated Romania’s airspace.

Poland has recorded another night of drone provocations from Russia and Belarus. The country’s Border Guard Service has reported heightened activity of the enemy targets attempting to violate its airspace, PAP reports.

Earlier, on 10 September, Russia launched 415 drones of various types and over 40 cruise and ballistic missiles against Ukraine. One person was killed and several were injured. Ukrainian air defenses destroyed more than 380 drones using mobile fire groups across the country. At the same time, 19 Russian drones crossed into Poland. The NATO state deployed several advanced aircraft, including F-35 and F-16, but still could not take down all the Russian targets.

Polish Minister of Interior Affairs Mariusz Kamiński describes the situation on the Polish-Belarusian border as “very tense.”

“Tonight, the Border Guard observed increased activity of Belarusian and Russian drones trying to cross Polish airspace,” the minister emphasizes.

When asked about reopening border crossings with Belarus, Kamiński reminded that the closure was imposed due to the Russian-Belarusian military exercises “Zapad-2025”.

During the drills, both countries tested an attack on Poland and a nuclear attack.

“The border will open only when we have full confidence that there are no threats or provocations to Poland. If our intelligence confirms that it is safe, we will reopen the border,” he added.

On 16 September, Belarus also announced that its forces practiced deploying Russia’s Oreshnik missile system, marking the first known training with the weapon system outside Russia.

The Oreshnik is a Russian intermediate-range ballistic missile first used operationally against Ukraine on 21 November 2024. It struck the missile production facility in Dnipro. The missile flies at hypersonic speeds around 10-11 Mach and carries multiple independently targetable warheads.

The suspension affects road and rail transport in both directions, hitting the main route that carries 90% of rail freight between China and the EU. In 2024, shipments via this route increased by 10.6%, and the value of goods rose by 85%, reaching €25.07 billion, as per Politico.

PKP Cargo warned that short delays are manageable, but prolonged border closure would force a rerouting of trade to southern corridors.

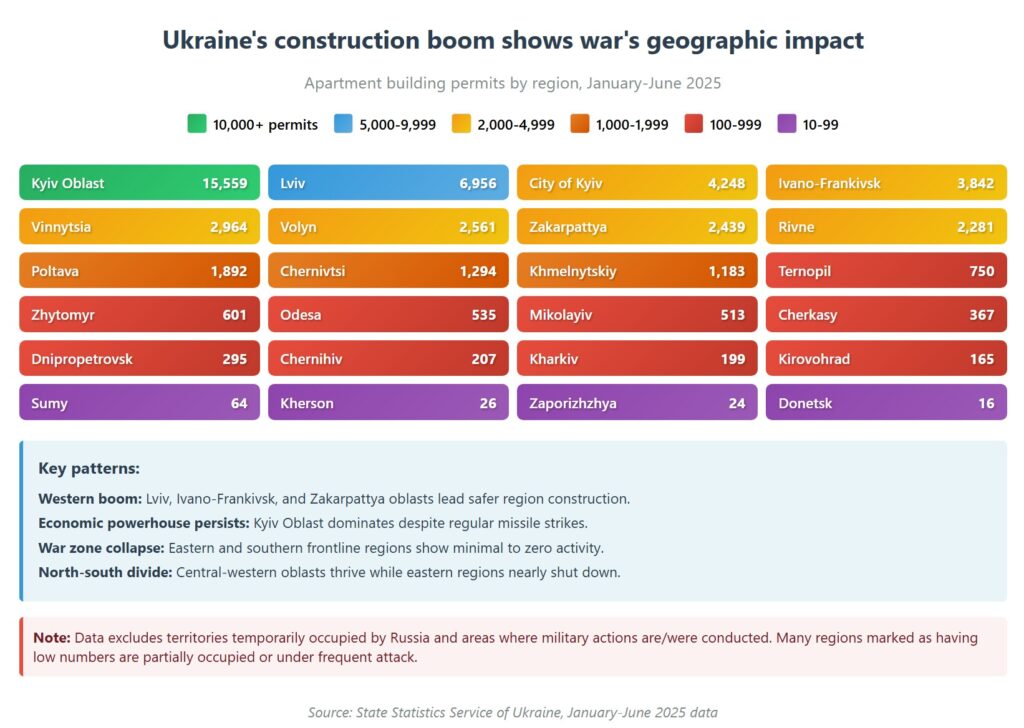

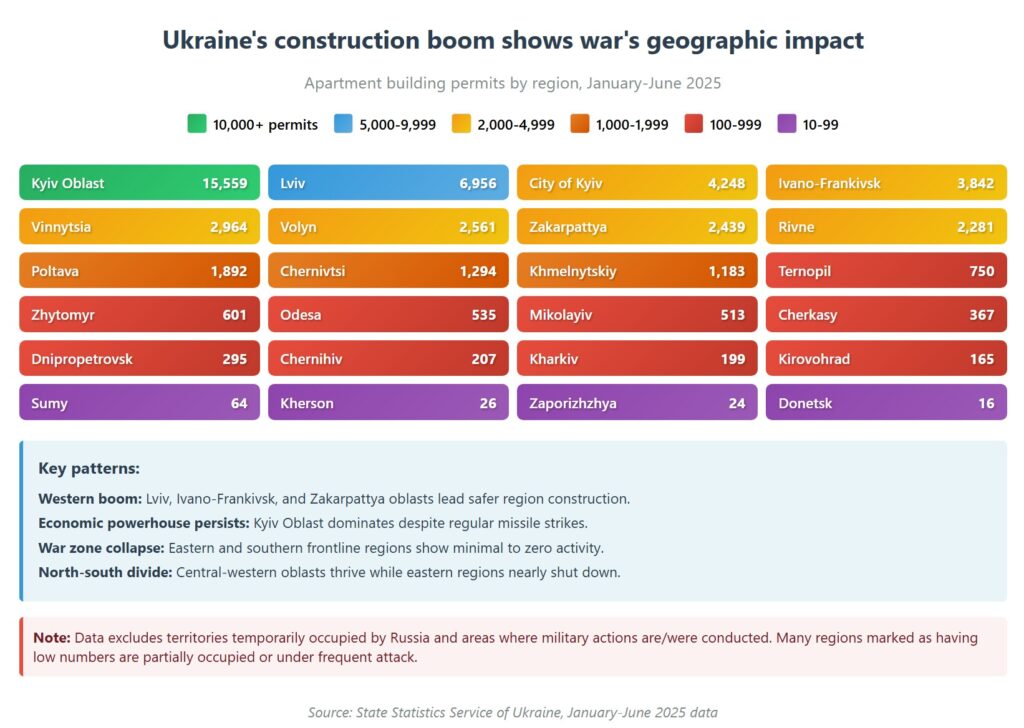

A 45% jump from last year defies wartime expectations across Ukraine’s economic heartland and western regions. Kyiv Oblast dominated with 15,559 apartment permits despite regular missile strikes.

At the same time, western strongholds Lviv (6,956) and Ivano-Frankivsk (3,842) attracted developers betting on safer locations, according to State Statistics Service data released on 18 September.

This construction revival comes despite the industry operating at roughly half of pre-war capacity. Before Russia’s invasion, Ukraine approved construction for 12.7 million square meters of housing in 2021. The war crashed that figure to 6.67 million in 2022, then 4.2 million in 2023.

The 2025 recovery follows the geographic logic of wartime Ukraine.

Kyiv Oblast’s 15,559 apartments represent a 130% increase from 2024, while Lviv Oblast’s 6,956 units reflect the region’s role as Ukraine’s migration hub. Meanwhile, frontline regions tell a different story: Donetsk managed just 16 apartment permits.

“Western Ukraine has now become a big construction site,” noted an analyst tracking western regions’ industrial real estate boom.

The apartment surge reflects deeper economic confidence despite ongoing strikes on Ukrainian cities. Construction companies have maintained optimism for four consecutive months, with their business confidence index hitting 54.0 in August—the only major economic sector firmly in positive territory.

This optimism translates into serious investment commitments.

Starting apartment construction requires long-term planning, secure financing, and confidence in demand, suggesting Ukraine’s business community sees stability ahead despite daily missile attacks.

The housing market has adapted to wartime realities, with mortgage lending surging by 62% in 2024. This growth is concentrated in government programs supporting key societal groups.

The 45% surge in construction permits coincides with foreign portfolio investors returning to Ukrainian real estate for the first time since the invasion began. Developers report institutional investors from countries spanning the UAE to Canada are now purchasing residential units in bulk, with some projects seeing foreign sales exceed domestic purchases.

“In our projects, the number of deals with foreigners sometimes exceeds the number of deals with Ukrainians,” said Irina Mikhaleva from Alliance Novobud, speaking to Interfax-Ukraine.

This suggests the construction recovery isn’t just domestic resilience—it’s attracting global capital, betting on Ukraine’s economic future.

Foreign investors from Spain, Japan, Türkiye, and other countries view Ukrainian real estate as promising assets. Some developers now guarantee 10% annual returns in foreign currency to attract international capital.

The return of portfolio investors represents a significant shift from 2022-2024, when the market focused mainly on end buyers.

International institutional money moving into Ukrainian real estate signals early positioning for the country’s eventual reconstruction phase, potentially indicating broader confidence in Ukraine’s long-term economic trajectory.

While the 45% growth sounds dramatic, it starts from a collapsed baseline. The 2.97 million square meters of new construction permits in early 2025 remain far below the 12.7 million approved in pre-war 2021. Ukraine’s construction sector still operates at roughly half its peacetime capacity.

Yet the geographic concentration reveals strategic adaptation. Safer western regions now absorb construction investment that once flowed to industrial eastern cities.

This represents a probable permanent demographic and economic shift that will outlast the war.

The World Bank estimates Ukraine needs $524 billion for reconstruction over the next decade, with housing suffering the most damage.

The current construction boom suggests Ukraine isn’t waiting for war’s end to begin rebuilding—it’s adapting and growing within wartime constraints while attracting international capital that sees opportunity in the country’s resilience.

Poland is preparing a record defense budget amid Russian drone attacks. On 18 September, Polish Defense Minister Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz announced that in 2026, the country’s defense spending will reach a record $55 billion, which is 4.8% of GDP, ArmyInform reports.

He emphasized that this is an all-time high for free Poland, though even this increase does not fully meet the country’s security needs.

“Between 2022 and 2026, the budget has tripled. Over four years, we have tripled spending on Polish state security, and we will continue to increase it because the needs are even greater,” Kosiniak-Kamysz said.

The Polish defense minister stressed that NATO allies must quickly reach 5% of GDP in defense spending.

“Within the next three to four years—by 2030—NATO countries should spend about 5%. We are talking 3.5% on ‘hard’ weapons and 1.5% on infrastructure,” he explained.

Kosiniak-Kamysz made these statements during his visit to Kyiv on 18 September, where he met his counterpart, Denys Shmyhal.

“Poland’s security line runs along the front between Ukraine and Russia. I fully understand this, and for many who try to forget, it needs to be reminded,” the Polish defense minister added.

Meanwhile, Poland and Ukraine are creating a joint operational group for unmanned aerial systems (UAVs), including representatives from both countries’ armed forces. The group will serve as a platform for coordinating and developing joint initiatives in UAV technology.

Ukraine has received the first shipment of military equipment under a new agreement between the United States and NATO, a NATO representative told Ukrainian media outlet Suspilne on Thursday.

The Prioritized Ukraine Requirements List (PURL) program is a new NATO-US mechanism that allows military aid to Ukraine to be financed collectively by allies, while weapons and equipment are drawn directly from American stockpiles.

The system is designed to speed up deliveries and share costs among NATO members, ensuring a steadier flow of support to Kyiv that does not rely on US political will.

The NATO official said additional aid packages are already on the way, with four packages financed so far through PURL.

The news comes a day after the Trump administration confirmed that Ukraine would soon receive its first assistance from NATO allies through US stockpiles under the PURL mechanism.

The agreement restores the flow of weapons from the United States to Kyiv after months of uncertainty.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said on Wednesday that the first PURL aid packages will include missiles for Patriot air defense and HIMARS systems.

The PURL initiative was announced by former US President Donald Trump on 14 July, 2025, pledging billions of dollars in weapons for Ukraine, to be purchased and distributed by European NATO allies. Trump specified plans to prepare up to 17 Patriot air defense systems for shipment.

By the end of August, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky reported that seven countries had committed to the program, contributing a total of $2 billion. Defense experts say Ukraine’s priorities remain focused on air defenses, interceptors, missile systems, rockets, and artillery.

The Council of Europe is preparing the International Claims Commission for Ukraine. The draft Convention has been published. The new agency will serve as the second stage of the international mechanism to compensate for damages caused by Russian aggression, following the international Damage Registry.

In July 2025, Ukrainian Defense Minister Denys Shmyhal stated that the cost of rebuilding Ukraine has reached $1 trillion. Since Russia shows no willingness to end the war, despite at least six calls from US President Donald Trump to Russian President Putin and an invitation to Alaska, the war of attrition continues, and total damages will keep rising.

The Commission will review claims and assign compensation to war victims, with Russia expected to pay reparations at the third stage. The document was agreed upon in The Hague after eight rounds of negotiations over 18 months.

The Convention covers the period from 24 February 2022, but Ukraine may propose extending it to 2014–2021, Babel reports. In 2014, Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea, forcibly changing the borders of another country and violating the international order established since World War II.

On 1 January 2028, the transition from the Damage Registry to the Commission will begin, allowing Ukraine to continue seeking reparations from Russia and protecting the rights of its citizens at the international level.

Earlier, Polish Foreign Minister Radosław Sikorski said providing security guarantees for Ukraine remains unclear, as no state “is willing to wage a war against the Kremlin.”

Sikorski recalled that Ukraine already had guarantees under the Budapest Memorandum, but they failed. The new arrangements, in his view, are also incapable of deterring Moscow.

“I don’t see anyone willing to fight with Russia”: Sikorski explains why security guarantees for Ukraine may fail like Budapest Memorandum

Ukrainian forces are conducting a counteroffensive operation in the Pokrovsk and Dobropillia areas of Donetsk Oblast, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy reported on 18 September.

The reported operation represents a significant strategic shift after Russia made major territorial gains in summer 2025 around Pokrovsk and surrounding areas, including a breakthrough near Dobropillia in August that Ukrainian forces subsequently contained and reversed.

“Since the start of the [counteroffensive] operation, our warriors have already liberated 160 square kilometers, and over 170 square kilometers have been cleared of the occupiers,” Zelenskyy said on Telegram.

He reported that seven settlements in the area have been liberated, and nine more “cleared of Russian presence.”

“Russian losses just since the start of this counteroffensive – in the Pokrovsk area alone, in these past weeks – are already more than 2,500, of which over 1,300 Russians have been killed,” Zelenskyy added.

He also said Ukraine has taken 100 Russian prisoners in the operation.

The counteroffensive comes after months of intense fighting around Pokrovsk, where Russia concentrated nearly 100,000 soldiers in what analysts called a force capable of attacking a European country.

Ukrainian forces successfully contained a Russian breakthrough near Dobropillia in August, where Moscow’s troops had advanced 15 kilometers before elite Ukrainian units, including the redeployed Azov Brigade, reversed their gains.

Pokrovsk represents the key to unlocking Russia’s broader campaign to capture all of Donetsk Oblast, serving as a critical supply hub for Ukrainian forces across the eastern front.

The city’s potential fall would severely compromise Ukraine’s defensive positions throughout the region and open pathways for deeper Russian advances toward Kostiantynivka and the broader Donbas fortress belt.

Recent intelligence indicates Russia is preparing fresh assaults with redeployed naval infantry brigades and additional armor after their summer failures.

Ukrainians over 60 now have the opportunity to voluntarily defend their country. The Ukrainian Parliament has passed a law allowing citizens over that age to join the military under a contract, which is entirely voluntary and without coercion, reports deputy Iryna Friz from the European Solidarity party.

“It’s important to understand that no compulsory mobilization is planned for this age group. This is purely a voluntary option for those who genuinely want to continue or start service after reaching the maximum age,” Friz explains.

The new law allows citizens over 60 who wish to serve to sign a contract with the approval of their commander and the General Staff.

A fitness assessment by a military medical commission is a mandatory requirement. Contracts are for one year, with a two-month probationary period and the possibility of extension.

Social media recently circulated rumors about mobilizing people over 60. The law clarifies that this is only a voluntary opportunity for those who have the health, strength, and willingness to serve.

© REUTERS

© 2025 Invision

The US president said he thought his personal relationship with Putin would help bring the conflict to an end

© AFP/Getty

Australia delivers a major blow to Russia’s oil profits. The country has slashed the price cap on Russian oil from $60 to $47.60 per barrel and imposed sanctions on 95 more vessels from Russia’s “shadow fleet.” The decision was coordinated with the EU, UK, Canada, New Zealand, and Japan.

Russian oil remains a key source of revenue that funds its military aggression against Ukraine. In 2025, profits from the oil and gas sector account for about 77.7% of Russia’s federal budget.

According to the International Liberty Institute, the main buyers of Russian oil remain Asian countries, as European markets are largely restricted by sanctions.

The Australian Foreign Ministry has stated that lowering the oil price cap from $60 per barrel to $47.60 will reduce the market value of Russian crude and help deprive Russia’s war economy of revenue from raw materials.

The government also maintains a total ban on Russian oil and petroleum product imports. More than 150 ships have been sanctioned since June 2025.

The latest measures target 95 tankers, with intelligence on 60 vessels provided to international partners by Ukraine’s sanctions group.

“Ukraine has also imposed national sanctions on the captains of 15 of these tankers,” Andrii Yermak, the head of the Ukrainian Presidential Office, reveals.

Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Andrii Sybiha has thanked his Australian counterpart Penny Wong for the decision.

“Australia is helping to restrict Russia’s ability to fund its war and undermine global peace. We value our strong partnership with Australia and continue to stand together for shared values,” he said.

Australia’s sanctions are part of a wider Western strategy to reduce the Kremlin’s energy income. Partner governments believe that only sustained pressure on Russia’s oil sector can significantly weaken its capacity to fund the war against Ukraine.

On 18 September around 10am, Russian forces struck the eastern Ukrainian city of Kostiantynivka with a FAB-250 bomb with a UMPK guiding module, killing 5 civilians, the National Police of Ukraine reported.

Kostiantynivka, in Donetsk Oblast, eastern Ukraine, is located near the front line and has been frequently targeted by Russian forces since the start of the full-scale invasion.

The FAB-250 is a Soviet-designed, 250-kilogram general-purpose bomb that Russia often modifies with glide kits such as the UMPK module to increase its range and accuracy.

The victims – three men and two women aged 62 to 74 – were killed in the street. Four apartment buildings were also damaged.

The Donetsk Regional Prosecutor’s Office has opened a pre-trial investigation into a potential war crime over the attack.