Ex-Midshipman Is Charged in Threat That Led to 2 Injuries at U.S. Naval Academy

© Jim Watson/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Jim Watson/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Scott McIntyre for The New York Times

© KUTV

© Violeta Santos Moura/Reuters

© Thomas Coex/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Poland fights a pro-Kremlin disinformation wave, PAP reports. Pro-Russian sentiments are rising in Poland, and the responsibility of politicians is to stop them, Prime Minister Donald Tusk said after Russian drone attacks on the country.

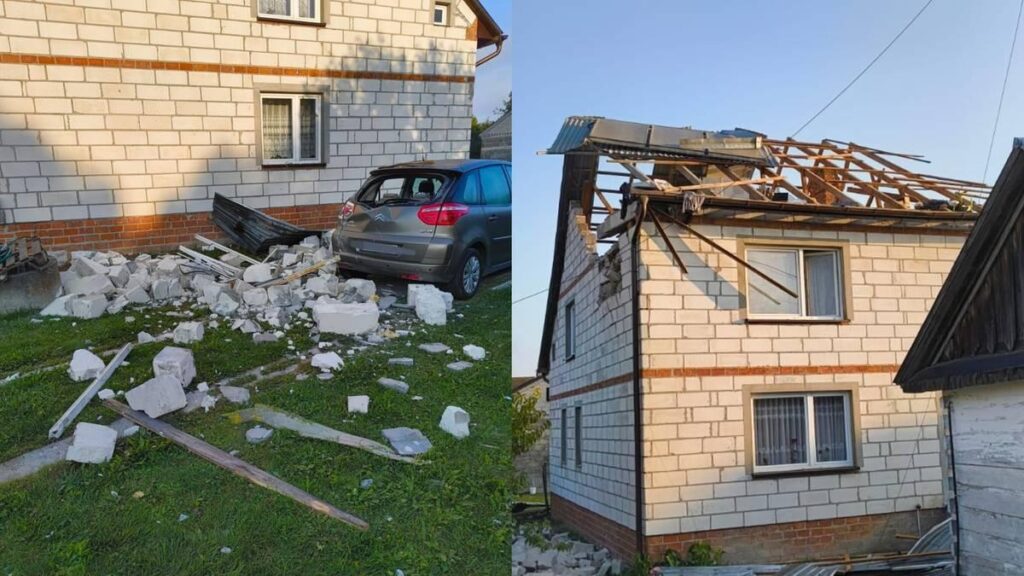

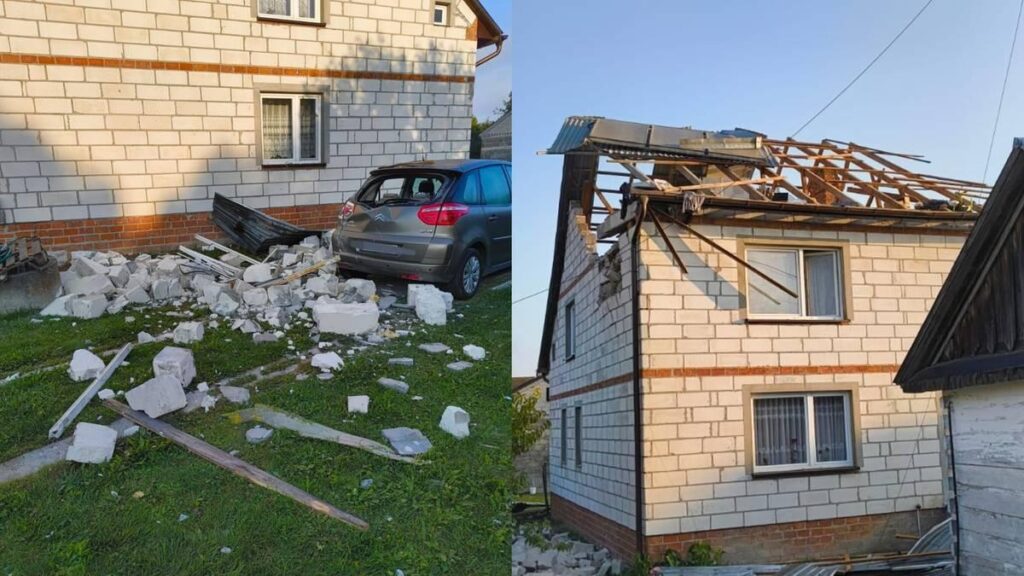

On 10 September, Russia launched 415 drones of various types and over 40 cruise and ballistic missiles against Ukraine. One person was killed and several were injured. Ukrainian air defenses destroyed more than 380 drones using mobile fire groups across the country. At the same time, 19 Russian drones crossed into Poland. The NATO state deployed several advanced aircraft, including F-35 and F-16, but still could not take down all the Russian targets.

“A wave of pro-Russian sentiment and anti-Ukrainian feeling is rising, created by the Kremlin using real fears and emotions,” Tusk wrote on X on Sunday, 14 September.

He emphasized that the task of politicians is to stop this wave before it affects society.

As expected, the attack caused strong fear and insecurity among Polish citizens. The country hosts points through which foreign weapons are delivered to Ukraine, heightening concerns.

These sentiments are actively supported by some Polish right-wing politicians and media, which build campaigns on anti-criminal emotions while ignoring the significant contributions of Ukrainians to Poland’s economy and society.

The Kremlin deliberately spreads disinformation and provokes confrontation between Poland and Ukraine to weaken Western support for Ukraine.

In 2024, the Ukrainians in Poland contributed about 2.7% of the country’s GDP, over 99 billion zlotys, which is nearly $20 billion . They established more than 77,700 private enterprises between 2022–2024, accounting for about 12% of all new businesses in the country during that period.

Earlier, Tusk assured that Polish services and the military know who is responsible for the drone attack.

“We will not be sensitive to manipulation and disinformation from Russia. Poland is confident about the sources, launch location, and intent of this action,” the Polish prime minister added.

The head of government urged Poles to rely only on verified information from official sources, including the military, services, and state media, to avoid panic and fake news.

© Chang W. Lee/The New York Times

© Martial Trezzini/Keystone, via Reuters

© Kenny Holston/The New York Times

© Jordan Gale for The New York Times

© Loren Elliott for The New York Times

© Loren Elliott for The New York Times

© Atul Loke for The New York Times

© Todd Anderson for The New York Times

© Anna Watts for The New York Times

© Lorenzo Bevilaqua/Disney General Entertainment Content, via Getty

© Prabin Ranabhat/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Atul Loke for The New York Times

© Prabin Ranabhat/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

© Adnan Abidi/Reuters

© Niranjan Shrestha/Associated Press

© Navesh Chitrakar/Reuters

© Navesh Chitrakar/Reuters

© Navesh Chitrakar/Reuters

© Salvatore Di Nolfi/EPA, via Shutterstock

© Navesh Chitrakar/Reuters

© Adrian Langtry/Shutterstock

© Anna Rose Layden for The New York Times

© Nicole Tung for The New York Times

© KHOU11

© Tierney L. Cross/The New York Times

© Jason Andrew for The New York Times

© Jason Andrew for The New York Times

© Ozan Kose/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

While Ukrainians marked 34 years of independence from Soviet rule, NBC News gave Russia’s foreign minister prime American television time to explain why Ukraine should surrender its sovereignty.

Sergey Lavrov used his “Meet the Press” platform to deny the invasion of Ukraine, dismiss President Zelenskyy as illegitimate, and set conditions on Ukraine’s right to exist by demanding territorial concessions.

The interview occurred on 24 August, 2025 – the anniversary of Ukraine’s 1991 declaration of independence from the USSR – as Lavrov presented the war as a defensive operation while rejecting the legitimacy of Ukraine’s leadership and borders.

When NBC’s Kristen Welker asked directly “Did Russia invade Ukraine?” Lavrov flatly denied the invasion, responding “No” and once again calling it instead a “special military operation” – a term that has been used by Russian officials since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Pressed on whether Putin recognizes Zelenskyy as Ukraine’s legitimate leader, Lavrov replied: “No, we recognize him as de facto head of the regime. And in this capacity, we are ready to meet with him.” He falsely claimed that according to Ukraine’s constitution, Zelenskyy is not legitimate.

Ukrainian officials have consistently rejected Russian legitimacy claims. Ukraine’s constitution allows the president to remain in office during wartime, and Zelenskyy was democratically elected in 2019 with over 73% of the vote.

Lavrov asserted that Ukraine has the right to exist only if it surrenders territories and populations to Russian control, demanding Ukraine “let people go” in occupied territories.

He referred to Ukraine’s eastern and southern regions using the term “Novorossiya” – a tsarist-era concept Russia employs to claim historic dominion over large portions of Ukrainian territory. The term historically encompassed areas including modern-day Ukraine’s Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, Kherson, Dnipropetrovsk, Mykolaiv, and Odesa regions.

Lavrov presented these territorial demands to American television audiences, placing conditions on Ukraine’s right to exist as a sovereign state. He referenced illegitimate, Russian-organized referendums in occupied territories as justification for territorial claims over internationally recognized Ukrainian territory.

Despite denying the invasion and demanding territorial concessions, Lavrov insisted Putin wants peace while simultaneously defending Russia’s military operation.

The interview occurred as Russian forces intensify operations across Donetsk Oblast, with fighting escalating around Dobropillia and other eastern Ukrainian positions.

The timing allowed Russia’s foreign minister to associate Ukrainian independence celebrations with discussions of territorial surrender on American television.

Last week, we were talking to each other about the fact that we were about to hit the second anniversary of 404 Media. The conversation was about what we should say in this blog post, which obviously led us to try to remember everything that has happened in the last year. “I haven’t considered a thing beyond what’s been five seconds behind or in front of me for the last year,” Sam said.

The last year has been a whirlwind not just for us but for, uhh, the country and the world. And we’ve been trying our absolute best to bring you stories you can’t find anywhere else about the wildest shit happening right now, which includes the Silicon Valley-led dismantling of the federal government, the deployment of powerful surveillance against immigrants and people seeking abortions, the algorithmic, AI-led zombification of “social” media, the end of anonymity on the internet, and all sorts of weird stuff that we see on our travels through the internet. As Sam noted, we have largely had our heads down trying to bring you the best tech journalism on the internet, which hasn’t left us a ton of time to think about long-term projects, blue-sky ideas, or what the best business strategies for growing this company would be.

Our guiding principle is something we said we would do on day one of starting this company: “We believe it is possible to create a sustainable, profitable media company simply by doing good work, making common-sense decisions about costs, and asking our readers to support us.” What we have learned in two years of building this company is that there is no secret to building a media company, and that there are also no shortcuts. When we work hard to publish an important article, more people discover us and more people subscribe to us, which helps solidify our business and allows us to do more and better articles. As our stories reach a larger audience, the articles often have more impact, more potential sources see them, and we get more tips, which leads to more and better articles, and so on.

In our second year as a media outlet, we’ve done too much impactful reporting to list out in this post. But to summarize some of the big ones:

On top of all of these, we’ve published some of the most moment-defining stories that, as Jason has said many times, are the types of things people talk about at the bar after work. Those include:

It has been a relief that this business strategy of “publish good articles and ask people to pay for journalism” still works, despite the fracturing of social media, the slopification of every major platform, AI being shoved into everything, and the rich and powerful trying to destroy journalism at every turn. That it is working is a testament to the support of our subscribers. We have no real way of knowing exactly where new subscribers come from or what ultimately led them to subscribe, but time and time again we have learned that the most important discovery mechanism we have is word of mouth. We have lost count of the number of times a new subscriber has said that they were told about 404 Media by a friend or a family member at a party or in a group text, so if you have told anyone about us, we sincerely thank you.

Photos by Sharon Attia

It wasn’t obvious when we started this company that it would actually work, though we hoped that it would.

In our post last year, we wrote, “We don’t have any major second-year plans to announce just yet in part because we have been heads down working on some of the investigations and scoops you’ve seen in recent days. The next year holds more scoops, more investigations, more silly blogs, more experiments, more impact, and more articles that hold powerful companies and people to account. We remain ambitious and are thinking about how to best cover more topics and to give you more 404 Media without spreading ourselves too thin.”

But we did take a moment to think about what has changed in the last year, and it turns out that quite a lot is different now than it was a year ago.

For one, we have cautiously begun to expand what we do. In the last year, we launched The Abstract, which is Becky Ferreira’s Saturday newsletter about science, which many of you have said you love and which helps us provide a sense of wonder and discovery when so much of what we report on is pretty bleak. We have been getting part-time (but very critical) help from Case Harts who is running and growing our social media accounts, which is helping us put our stories more natively on Instagram, TikTok, YouTube, and other platforms that we do not control but which nonetheless remain important for us to be on. Matthew Gault has started covering the military industrial complex, AI, weird internet, and dad internet beat for us, and has done a remarkable job at it. Rosie Thomas is our current intern who has published critical reporting about the sale of GPS trackers on TikTok, protests at the Tesla Diner, and the difficult decisions voice actors need to make about whether they should let AI train on their voices.

All of this has changed what 404 Media looks like, a little bit. We have spent a lot of time thinking about what it would look like to expand beyond this, why people subscribe to us, what it would mean to go further, and what the four of us are actually capable of handling outside of the journalism. Because of your support we are in a place where we’re able to ask questions beyond “Can we survive?” We’re able to ask questions like: “Should we try to make this bigger, and what does that look like?”

We feel incredibly lucky that we are now able to ask ourselves these questions, because there was no guarantee that 404 Media would ever work, and we are forever grateful to everyone who has supported us. You have helped us prove that this model can work, and every day we are delighted to see that other journalists are striking out on their own to create their own publications.

We are still DIYing lots of things. Emanuel is still doing customer support. Jason is still ordering, packing, and mailing merch. Sam is putting together events and parties. Joseph is doing an insane number of things behind the scenes, managing the podcast, working closely with one of our ad partners, and fixing technical issues. As we have grown, these tasks have started to take more and more time, which raises all sorts of questions about when and if we should get help with them. Should we do more events? Should we get someone to help us with them? What does that look like logistically and financially? These are the things that we’re working out all the time. It becomes a question of how much can we juggle while still having some semblance of work/life balance, and while making sure that we’re still putting the journalism first.

Other things that have happened:

Like last year, we don’t have anything crazy to announce for year three. But we hope that you will continue to support us (or, if you’re finding us through this post, will consider subscribing). We discussed some of our hopes and dreams for year three in our latest bonus podcast that went out to supporters this week. We are all trying our very best to bring you important, impactful work as often as possible, and we are trying to be as clear as possible about what’s working, what’s not, and how we’re trying to build this company. So far, that strategy has worked really well, and so we don’t intend to change it now.

August—2025. The new limited edition 4K Blu-ray of the 2003 film Master and Commander has sold out everywhere. Secondary markets are now battlefields.

There are two kinds of people in this world: those who read the above sentences and feel an intense pain and yearning for camaraderie and combat on the high seas, and those who have never seen Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World.

Recent events in the South Caucasus show how the authoritarian playbook is exported and adapted to suit local contexts. From Armenia’s clergy allegedly plotting coups, to Azerbaijan raiding Russian state-funded media offices as retribution, to Georgia’s mass arrests of opposition leaders, the region revealed how authoritarianism and resistance to it adapts and spreads through digital-age tactics.

The three nations of the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, have long occupied a place of strategic and symbolic importance for Russia. The region is a vital transit corridor linking Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, making it a coveted prize for energy routes and geopolitical influence. For Moscow, the South Caucasus has always been more than a neighboring periphery, it is an enduring obsession. And perhaps more so now, as Russia’s position in the Middle East has weakened following setbacks in Syria and its diminished sway in Iran. Today, the Kremlin’s desire to assert control in the South Caucasus is as strong as ever. Yet in each of these three countries, Moscow’s efforts to shape events and narratives are meeting unprecedented resistance. The divergent responses—ranging from defiance to accommodation—highlight how the authoritarian playbook is being adapted, contested, and exported across the region.

So what constitutes this playbook? Legal weaponization through foreign agent laws, criminalization of dissent with disproportionate penalties, systematic impunity for state violence, economic warfare against independent media, and international narrative manipulation. Below are three examples:

Armenia, once Moscow’s closest ally in the South Caucasus, has openly expressed disillusion with years of Russian inaction during regional crises. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan now warns of “hybrid actions and hybrid war” from Russian circles, without directly blaming the Kremlin, while the EU and France step in to support his decision to jail clergymen in defence of Armenian democracy. The clerics were accused of plotting a coup. Fingers were also pointed at Russian-Armenian businessman Samvel Karapetyan, the alleged orchestrator. It was, in one analyst’s words. Moscow’s “Ivanishvili 2.0 operation”, a reference to Bidzina Ivanishvili, the billionaire founder and de facto leader of Georgian Dream, Georgia’s ruling party since 2012. Georgian Dream, under Ivanishvili, has steered Georgia in an increasingly illiberal and pro-Russian direction. But for a couple of years now, the Armenian government has been gradually distancing itself from Russia, hedging its bets rather than relying on Moscow to guarantee security. In the aftermath of the alleged coup attempt, Armenia’s Foreign Minister bluntly told Russian officials that they “must treat Armenia’s sovereignty with great respect and never again allow themselves to interfere in our internal affairs.” Pashinyan has of late made conciliatory gestures towards both of Armenia’s arch-rivals, Azerbaijan and Turkey. The loss of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan — while Russian peacekeepers stood by — largely drove Armenia toward European integration as an existential necessity. Armenia's experience with alleged coup plot, and its possible Russian backing, shows how the playbook adapts to different political contexts, exploiting religious institutions and diaspora networks to destabilize governments that drift from Moscow's orbit.

The raid on Russian state media offices in Baku last week sent an unmistakable message about the limits of Moscow’s influence in the region. The targeting of Sputnik journalists came after violent police action in Russia in which two Azerbaijani nationals were killed, an incident Baku condemned as ethnically motivated. For years, Azerbaijan has been systematically moving out of Moscow’s orbit, growing closer to Turkey and unafraid to assert itself in disputes with Russia. The arrests of Russian journalists represent more than bilateral tensions; they signal how even traditionally Moscow-aligned states now calculate that defying Russia carries fewer costs than submission. Russia’s response — summoning the Azerbaijani ambassador and protesting the “dismantling of bilateral relations” — revealed Moscow’s diminished leverage. Azerbaijan’s confidence stems from military victories in Nagorno-Karabakh, increased energy exports to Europe, and strategic ties with Turkey that provide alternatives to a subservient partnership with Russia. Azerbaijan's bold move illustrates another dimension of the regional dynamic: how countries with strong alternative partnerships can successfully resist Russian pressure tactics, even when those tactics include media warfare and diplomatic intimidation.

Georgia presents the starkest illustration of both the Kremlin’s enduring shadow and the systematic deployment of authoritarian tactics. The ruling Georgian Dream party has implemented what Transparency International calls a “full-scale authoritarian offensive,” with eight opposition figures jailed in just a single week. The crackdown follows months of mass protests against the foreign agent law — a carbon copy of Russian legislation designed to crush civil society. Among those arrested is Nika Gvaramia, the former head of the country’s leading opposition TV channel, who spent a year in prison, received the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award, and emerged to found his own political party. Now Gvaramia faces another eight-month sentence plus a two-year ban from holding office, an example of how the repressive state systematically eliminates viable opposition while maintaining a veneer of legal process.

The foreign agent law itself has become a remarkably successful Russian export — a tool used from Nicaragua to Egypt to stigmatize independent civil society as “trojan horses” serving foreign interests. In Georgia, the law forces organizations receiving over 20% foreign funding to register as entities “pursuing the interests of a foreign power,” enabling harsh monitoring requirements and the systematic isolation of critics.

Since Russia pioneered the foreign agent model in 2012, it has been adopted by countries including Nicaragua, where it has been used to shut down over 3,000 civil society organizations, and Hungary, where officials explicitly cited the US FARA law as justification when facing international criticism. The model's appeal to authoritarian leaders lies in its appearance of legitimacy — claiming to mirror democratic precedents while systematically dismantling civil society. The chilling effect extends beyond legal restrictions.

Physical attacks on journalists have become routine, with not a single perpetrator facing accountability. Instead, the state's message is unmistakable: challenge us, and you will pay. According to the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, economic pressure has become a critical threat to media freedom globally, with the economic indicator hitting an “unprecedented, critical low” of 44.1 points — Georgia exemplifies this trend through its systematic economic warfare against independent outlets.

The story of one Georgian journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli, founder of two independent newsrooms Batumelebi and Netgazeti, is a textbook case of how modern authoritarianism operates through seemingly proportional responses to manufactured crises.

Amaglobeli was taken into custody for placing a solidarity sticker reading “Georgia goes on strike” and subsequently slapping Police Chief Irakli Dgebuadze after hours of degrading treatment, including watching colleagues being beaten by police.

Amaglobeli was arrested for assaulting a police officer, but many suspect her journalism was the real target. The charges against Amaglobeli — from “distorting a building’s appearance” for the removable sticker to “attacking an officer” — could mean seven years in prison. Evidence has been manipulated, timelines don’t match, and the authorities’ narrative shifts with each wave of international criticism. During detention, she was subjected to degrading treatment — insulted, spat upon, and denied access to water and toilets.

“It’s not only her being on trial, it’s independent media being on trial in Georgia,” said Irma Dimitradze, Amaghlobeli’s colleague who is now leading the global campaign to free her. She was speaking at Coda’s annual ZEG Fest along with Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of the Committee to Protect Journalists; human rights barrister Caoilfhionn Gallagher, and Nobel laureate and co-founder of Rappler Maria Ressa. All three argued that the systematic nature of the persecution of Amaglobeli reveals the broader strategy that’s similar the world over. Her case demonstrates how authoritarian systems create conditions where any human response to injustice becomes criminal evidence.

As Caoilfhionn Gallagher put it: “You are not dealing here with a rule of law compliant system... there’s a whole series of absolutely farcical things which have happened in this case so far. The criminal investigation was headed by the officer who was the alleged victim. I mean these are…you couldn’t make this stuff up, really... it is clear that in Georgia you are not going to get a fair trial. She hasn’t had due process yet and really what's going to make the difference here is ensuring that the world is watching and that there's a proper international strategy.”

After a 38-day hunger strike, Amaglobeli remains defiant, standing for hours in court, refusing to sit, determined to show she cannot be broken. Her symbolic gesture of holding up Ressa’s book, “How to Stand Up to a Dictator”, during court appearances has become an icon of resistance.

“We know,” said Ressa, “that journalism around the world is under attack.” With 72% of the world’s population living under authoritarian rule, added Ressa, “the time to protect our rights is now.” Gallagher spoke about the “power of international solidarity,” how what authoritarians fear is “journalism with a purpose, with an editorial line which is designed to undermine the false narratives and the gaslighting on a grand scale.”

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Resisting the Authoritarian Playbook in the South Caucasus appeared first on Coda Story.

Armenian authorities should "seriously" consider banning the broadcast of Russian television channels in Armenia, Armenian Parliament Speaker Alen Simonyan said on July 1, citing concerns over interference and deteriorating ties.

"We must very seriously discuss the suspension of the Russian television channel broadcast in the territory of Armenia," Simonyan told reporters, according to Armenpress. He criticized recent content aired by Russian state broadcasters, which the Armenian government has denounced as harmful to bilateral ties.

The remarks come as Armenia continues to pivot away from Moscow's sphere of influence and seeks to bolster ties with the West.

Simonyan suggested that individuals connected to Armenian-Russian oligarch Samvel Karapetyan may be financing efforts to meddle in Armenia's internal matters.

"If there are channels that allow themselves to interfere in Armenia’s domestic affairs, perhaps we ought to respond likewise, by at least banning their entry into the homes of our society," he said.

Tensions between Armenia and Russia have mounted since Moscow's failure to intervene during Azerbaijan's military operation in Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2023, which resulted in the mass displacement of ethnic Armenians.

In April, Armenian President Vahagn Khachaturyan signed a law initiating the country's formal accession process to the European Union.

Though symbolic, the legislation marks a significant political shift, embedding European integration into Armenian law. The bill, passed by parliament in March, was backed by 64 lawmakers and opposed by seven.

Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has said that EU membership would require a referendum, while the Kremlin warned that joining both the EU and the Russian-led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) is "simply impossible." The EAEU, established in 2015, includes Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia, and Kyrgyzstan.

The Kyiv IndependentOleksiy Sorokin

The Kyiv IndependentOleksiy Sorokin

Editor's note: The story was updated after the Sputnik news agency disclosed the names of those detained in Baku.

Azerbaijani police detained two alleged agents of Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB) on June 30 following searches at the Baku office of the Russian state-controlled news agency Sputnik, the Azerbaijani news outlet Apa.az reported.

Sputnik later elaborated that Igor Kartavykh, chief editor of Sputnik Azerbaijan, and Yevgeniy Belousov, managing editor, had been detained in Baku. The agency called the allegations that the detainees were FSB agents "absurd."

The move comes amid a major deterioration in Russian-Azerbaijani relations that followed the detention of over 50 Azerbaijanis as part of a murder investigation in Yekaterinburg on June 27. Two people died during the detentions, and three others were seriously injured.

The searches in the office of the Russian propaganda media outlet, which operates as a local branch of Russian state news agency Russia Today (RT), began on June 30.

The Russian propagandist Margarita Simonyan, editor-in-chief of Russia Today, said that representatives of the Russian embassy in Baku were on their way to Sputnik's office. Sputnik employees were offline and probably did not have access to phones, she added.

According to Simonyan, some of Sputnik's employees were Russian citizens.

The Azerbaijani government ordered in February that the activities of Sputnik's Azerbaijani office be suspended.

The authorities said that the move was intended to ensure parity in the activities of Azerbaijan's state media abroad and foreign journalists in the country. This meant that the number of Sputnik Azerbaijan journalists working in Baku was to be equal to the number of journalists of the Azerbaijani news agency Azertadzh in Russia.

As a result, Sputnik Azerbaijan had to reduce its staff from 40 people to one but refused to do so and continued to operate despite the Azerbaijani government's decision, according to Apa.az.

As the Russian-Azerbaijani relations deteriorate, Azerbaijan has cancelled all planned cultural events hosted alongside Russian state and private organizations, the country's Culture Ministry announced on June 29.

The announcement followed the deaths of two Azerbaijani citizens during police raids in the Russian city of Yekaterinburg.

Azerbaijan’s Foreign Ministry said on June 28 that Ziyaddin and Huseyn Safarov had died during a raid carried out by Russian authorities. Azerbaijan called the killings "ethnically motivated" and "unlawful" actions.

Baku called for the perpetrators to be brought to justice and said it expected Moscow to conduct a comprehensive investigation into the incident.

In the meantime, the Russian Foreign Ministry said that the detentions were carried out as part of an investigation into serious crimes. Foreign Ministry spokesperson Maria Zakharova claimed that these were cases related to murders committed in 2001, 2010, and 2011.

The Kyiv IndependentKollen Post

The Kyiv IndependentKollen Post

Ukrainian journalist Vladyslav Yesypenko was released on June 20 after more than four years of detention in Russian-occupied Crimea, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty reported.

Yesypenko, a freelance contributor to Crimea.Realities, a regional project of RFE/RL's Ukrainian Service, reported on various issues in Crimea before being detained by Russia’s FSB in March 2021.

He was accused of espionage and possession of explosives, charges he denied, and later sentenced to five years in prison by a Russian-controlled court.

Yesypenko said he was tortured, including with electric shocks, to force a confession, and was denied access to independent lawyers for nearly a month after his arrest.

RFE/RL welcomed his release, thanking the U.S. and Ukrainian governments for their efforts. Yesypenko has since left Russian-occupied Crimea.

“Vlad was arbitrarily punished for a crime he didn’t commit… he paid too high a price for telling the truth about occupied Crimea,” said RFE/RL President Steven Kapus.

During his imprisonment, Yesypenko became a symbol of press freedom, receiving several prestigious awards, including the Free Media Award and PEN America’s Freedom to Write Award.

His case drew support from human rights groups, the National Union of Journalists of Ukraine, and international advocates for media freedom.

Russia invaded and unlawfully annexed Crimea in 2014, cracking down violently on any opposition to its regime.

Following Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Kremlin toughened its grip on dissent, passing laws in March 2022 that prohibit what authorities label as "false" criticism of Russia's war.

The Kyiv IndependentDaria Shulzhenko

The Kyiv IndependentDaria Shulzhenko

Since the “social media is bad for teens” myth will not die, I keep having intense conversations with colleagues, journalists, and friends over what the research says and what it doesn’t. (Alice Marwick et. al put together a great little primer in light of the legislative moves.) Along the way, I’ve also started to recognize how slipperiness between two terms creates confusion — and political openings — and so I wanted to call them out in case this is helpful for others thinking about these issues.

In short, “Does social media harm teenagers?” is not the same question as “Can social media be risky for teenagers?”

The language of “harm” in this question is causal in nature. It is also legalistic. Lawyers look for “harms” to place blame on or otherwise regulate actants. By and large, in legal contexts, we talk about PersonA harming PersonB. As such, PersonA is to be held accountable. But when we get into product safety discussions, we also talk about how faulty design creates the conditions for people to be harmed due to intentional, malfeasant actions by the product designer. Making a product liability claim is much harder because it requires proving the link of harm and the intentionality to harm.

Risk is a different matter. Getting out of bed introduces risks into your life. Risk is something to identify and manage. Some environments introduce more potential risks and some actions reduce the risks. Risk management is a skill to develop. And while regulation can be used to reduce certain risks, it cannot eliminate them. And it can also backfire and create more risks. (This is the problem that María Angel and I have with techno-legal solutionism.)

Let’s unpack this a bit by shifting contexts and thinking about how we approach risks more generally.

Skiing is understood to be a risky sport. As we approach skiing season out here in the Rockies, I’m bracing myself for the uptick in crutches, knee wheelies, and people under 40 using the wheelchair services at the Denver airport. There is also a great deal of effort being put into trying to reduce the risk that someone will leave the slopes in this state. I’m fascinated by the care ski instructors take in trying to ensure that people who come to the mountains learn how to take care. There’s a whole program here for youngins designed to teach them a safety-first approach to skiing.

And there’s a whole host of messaging that will go out each day letting potential skiers know about the conditions. We will also get fear-mongering messages out here, with local news reporting on skiers doing stupid things and warnings of avalanches that too many folks will ignore. And there will be posters at the resorts telling people to not speed on the mountains because they might kill a kid. (I think these posters are more effective as scaring kids than convincing skiers to slow down.)

No matter what messaging goes out, people will still get hurt this season like they do every season. And so there are patrollers whose job it is to look for people in high-risk situations and medics who will be on hand to help people who have been injured. And there’s a whole apparatus structured to get them of the mountain and into long-term care.

Unless you’re off your rocker, you don’t just watch a few YouTube videos and throw yourself down a mountain on skis. People take care to learn how to manage the risks of skiing. Or they’re like me and take one look at that insanity and dream of a warm place by a fire or sitting in a hot tub instead of spending stupid amounts of money to introduce that kind of risk into their lives.

The stark reality is that every social environment has risks. And one of the key parts of being socialized through childhood into adulthood is learning to assess and respond to risks.

Consider walking down the street in a busy city. As any NYC parent knows, there are countless near-heart attacks that occur when trying to teach a 2-year-old to stop at the corner of the sidewalk. But eventually they learn to stop. And eventually they learn to not bowl people over while riding their scooter down that sidewalk. And then the next stage begins — helping young people learn to look both ways before crossing the street, regardless of what is happening with the light, and convincing them to maintain constant awareness about their environment. And eventually that becomes so normal that you start to teach your child how to J-walk without getting a ticket. And eventually, the child turns into a teenager who wanders the city alone, J-walking with ease while blocking out all audio signals with their headphones. But then take that child — or an American adult — to a city like Hanoi and they’ll have to relearn how to cross a street because nothing one learns in NYC about crossing streets applies to Hanoi.

Is crossing the street risky? Of course. But there’s a lot we can do to make it less risky. Good urban design and functioning streetlights can really help, but they don’t make the risk disappear. And people can actually cross a street in Hanoi, even though I doubt anyone would praise the urban design of streets and there are no streetlights. While design can help, what really matters for navigating risk is rooted in socialization, education, and agency. Mixed into this is, of course, experience. The more that we experience crossing the street, the easier it gets, regardless of what you know about the rules. And still, the risk does not entirely disappear. People are still hit by cars while crossing the street every year.

Can social media be risky for youth? Of course. So can school. So can friendship. So can the kitchen. So can navigating parents. Can social media be designed better? Absolutely. So can school. So can the kitchen. (So can parents?) Do we always know the best design interventions? No. Might those design interventions backfire? Yes.

Does that mean that we should give up trying to improve social media or other digital environments? Absolutely not. But we must also recognize that trying to cement design into law might backfire. And that, more generally, technologies’ risks cannot be managed by design alone.

Fixating on better urban design is pointless if we’re not doing the work to socialize and educate people into crossing digital streets responsibly. And when we age-gate and think that people can magically wake up on their 13th or 18th birthday and be suddenly able to navigate digital streets just because of how many cycles they took around the sun, we’re fools. Socialization and education are still essential, regardless of how old you are. (Psst to the old people: the September that never ended…)

In the United States, we have a bad habit of thinking that risks can be designed out of every system. I will never forget when I lived in Amsterdam in the 90s, and I remarked to a local about how odd I found it that there were no guardrails to prevent cars from falling into the canals when they were parking. His response was “you’re so American” which of course prompted me to say, “what does THAT mean?” He explained that, in the Netherlands, locals just learned not to drive their cars into the canals, but Americans expected there to be guardrails for everything so that they didn’t have to learn not to be stupid. He then noted out that every time he hears about a car ending up in the canal, it is always an American who put it there. Stupid Americans. (I took umbrage at this until, a few weeks later, I read a news story about a drunk American driving a rental into the canal.)

Better design is warranted, but it is not enough if the goal is risk reduction. Risk reduction requires socialization, education, and enough agency to build experience. Moreover, if we think that people will still get hurt, we should be creating digital patrols who are there to pick people up when they are hurt. (This is why I’ve always argued that “digital street outreach” would be very valuable.)

People certainly face risks when encountering any social environment, including social media. This then triggers the next question: Do some people experience harms through social media? Absolutely. But it’s important to acknowledge that most of these harms involve people using social media to harm others. It’s reasonable that they should be held accountable. It’s not reasonable to presume that you can design a system that allows people to interact in a manner where harms will never happen. As every school principal knows, you can’t solve bullying through the design of the physical building.

Returning to our earlier note on product liability, it is reasonable to ask if specific design choices of social media create the conditions for certain kinds of harms to be more likely — and for certain risks to be increased. Researchers have consistently found that bullying is more frequent and more egregious at school than on social media, even if it is more visible on the latter. This makes me wary of a product liability claim regarding social media and bullying. Moreover, it’s important to notice what schools have done in response to this problem. They’ve invested in social-emotional learning programs to strengthen resilience, improve bystander approaches, and build empathy. These interventions are making a huge difference, far more than building design. (If someone wants to tax social media companies to scale these interventions, have a field day.)

Of course, there are harms that I do think are product liability issues vis-a-vis social media. For example, I think that many privacy harms can be mitigated with a design approach that is privacy-by-default. I also think that regulations that mandate universal privacy protections would go a long way in helping people out. But the funny thing is that I don’t think that these harms are unique to children. These are harms that are experienced broadly. And I would argue that older folks tend to experience harms associated with privacy much more acutely.

But even if you think that children are especially vulnerable, I’d like to point out that while children might need a booster seat for the seatbelt to work, everyone would be better off if we put privacy seatbelts in place rather than just saying that kids can’t be in cars.

I have more complex feelings about the situations where we blame technology for societal harms. As I’ve argued for over a decade, the internet mirrors and magnifies the good, bad, and ugly. This includes bullying and harassment, but it also includes racism, xenophobia, sexism, homophobia, and anti-trans attitudes. I wish that these societal harms could be “fixed” by technology; that would be nice. But that is naive.

I get why parents don’t want to expose children to the uglier parts of the world. But if we want to raise children to be functioning adults, we also have to ensure that they are resilient. Besides, protecting children from the ills of society is a luxury that only a small segment of the population is able to enjoy. For example, in the US, Black parents rarely have the option of preventing their children from being exposed to racism. This is why white kids need to be educated to see and resist racism. Letting white kids live in “colorblind” la-la-land doesn’t enable racial justice. It lets racism fester and increases inequality.

As adults, we need to face the ugliness of society head on, with eyes wide open. And we need to intentionally help our children see that ugliness so that they can be agents of change. Social media does make this ugly side more visible, but avoiding social media doesn’t make it go away. Actively engaging young people as they are exposed to the world through dialogue allows them to be prepared to act. Turning on the spicket at a specific age does not.

I will admit that one thing that intrigues me is that many of those who propagate hate are especially interested in blocking children from technology for fear that allowing their children to be exposed to difference might make them more tolerant. (No, gender is not contagious, but developing a recognition that gender is socially and politically constructed — and fighting for a more just world — sure is.) There’s a long history of religious communities trying to isolate youth from kids of other faiths to maintain control.

There’s no doubt that media — including social media — exposes children to a much broader and more diverse world. Anyone who sees themselves as empowering their children to create a more just and equitable world should want to conscientiously help their children see and understand the complexity of the world we live in.

In the early days of social media, I was naive in thinking that just exposing people to people around the world to each other would fundamentally increase our collective tolerance. I had too much faith in people’s openness. I know now that this deterministic thinking was foolish. But I have also come to appreciate the importance of combining exposure with education and empathy.

Isolating people from difference doesn’t increase tolerance or appreciation. And it won’t help us solve the hardest problems in our world — starting with both inequity and ensuring our planet is livable for future generations. Instead, we need to help our children build the skills to live and work together.

Put another way, to raise children who can function in our complex world, we need to teach them how to cross the digital street safely. Skiing is optional.