Bilhorod-Dnistrovskyi Port’s privatization completed

The White House has urged European countries to follow the US and impose restrictive measures on India for its purchases of Russian oil, which fund the war in Ukraine, India Today reports.

US tariffs on Indian goods

In August 2025, the US raised tariffs on goods from India up to 50%, criticizing New Delhi for supporting Russia’s economic machinery. At the same time, Washington has not imposed sanctions on China, the main sponsor of the war and Moscow’s key economic partner.

A Russian drone caught filming its own camera test in a Chinese factory before being shot down in Ukraine

India has criticized the US decision, pointing out double standards: Europe itself continues to purchase oil from Russia. EU–Russia trade in 2024 reached €67.5 billion in goods and €17.2 billion in services. Europe also imported a record 16.5 million tons of Russian LNG, the highest number since 2022.

Many critical Russian exports remain unrestricted, including palladium for the US automotive industry, uranium for nuclear power plants, fertilizers, chemicals, metals, and equipment.

Sources report that Trump also pressured India to nominate him for the Nobel Peace Prize. After being rejected, he responded with tariffs. This has prompted India to strengthen its ties with China and reinforced so-called anti-American cooperation among the so-called “axis of upheaval” countries.

Today, the US administration seeks to have Europe join in sanction pressure on New Delhi if India does not stop buying Russian oil.

The National Bank of Ukraine reported businesses improved their economic expectations in August, with the business activity expectations index rising to 49.0 from 48.3 in July.

The index, based on monthly surveys of real-sector companies about their expected performance, uses 50 as the neutral threshold, meaning Ukrainian businesses remain slightly pessimistic but are moving toward stability.

Construction companies led the optimism, with their index hitting 54.0 in August. They have stayed positive for four consecutive months as reconstruction projects and sustained domestic demand provide steady work.

Trading firms have maintained optimism for six months as new harvest supplies reach markets and consumer spending holds up.

Even industrial companies, hammered by Russian strikes on production facilities, maintained steady expectations at 48.7 despite ongoing destruction and soaring raw materials and labor costs.

Service companies remained the most cautious at 47.0, citing expensive logistics, higher electricity prices, and skilled worker shortages.

The drivers behind this cautious improvement include energy stability, decelerating inflation, and what the NBU calls “brisk consumer sentiment”—suggesting Ukrainian purchasing power hasn’t collapsed despite the war.

But this domestic resilience exists only because foreign partners keep Ukraine’s external accounts afloat. Balance of payments data released alongside the business survey reveals the underlying dependency.

The current account deficit nearly doubled to $4.1 billion in July compared to last year, as imports surged 19.9% while exports managed only 3.1% growth.

Ukraine needs more machinery for reconstruction and defense, while traditional export sectors like grain and metals struggle under wartime constraints.

Foreign direct investment collapsed from $3.2 billion to just $1.1 billion in the first seven months of 2025. Instead, governments and international organizations provide the lifeline: $17.8 billion in net financial flows this year compared to just $7.3 billion last year.

Ukraine’s $43 billion reserves look healthy, but exist because donors keep filling the tank. Without this support, the domestic confidence businesses report would evaporate quickly.

This combination reveals both the success and the limits of Western aid strategy. The money works—Ukraine’s economy functions and companies plan for the future rather than just surviving day-to-day. Businesses can focus on reconstruction and meeting consumer demand because external support handles the macroeconomic gaps.

But the deepening dependency raises sustainability questions.

How long can donor countries maintain $17-18 billion annual flows? What happens should there be military setbacks, which would reduce confidence in Ukraine’s long-term viability?

For now, the arrangement holds: international support enables domestic stability, which maintains business confidence, which keeps the economy functioning.

Whether this virtuous cycle continues depends on factors far beyond Ukraine’s borders—donor fatigue, military developments, and shifting political priorities in supporting countries.

The cautious optimism Ukrainian businesses report may prove justified, but only if external support continues at unprecedented levels.

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

© Andrew Harnik/Getty Images

© Haiyun Jiang /The New York Times

On paper, Russia’s economy looks like a fortress: GDP rising, defense spending at record highs, oil billions still rolling in. No wonder many ask if sanctions have failed — or if Putin’s war economy is strong enough to sustain his war in Ukraine indefinitely. But a June 2025 report from CSIS — one of Washington’s most respected think tanks — warns that this fortress is hollow, and the cracks are already spreading.

Support our media in wartime your help fuels every storyRussia’s “growth” is fake — a wartime sugar high before the crash.

Yes, GDP fell 2.1% in 2022, then rebounded with 3.6% growth in 2023 and 4.1% in 2024. But that wasn’t real recovery — it was deficit spending on weapons that get blown up in Ukraine.

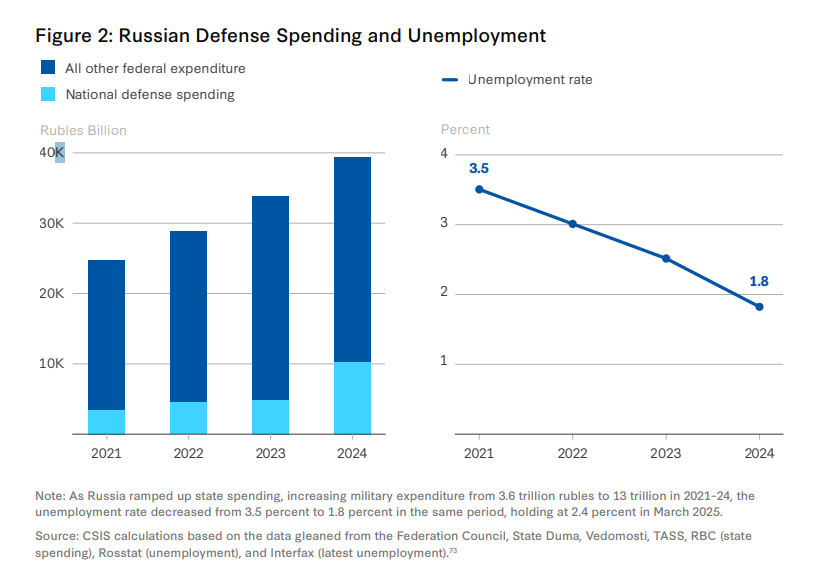

Moscow poured a record 13.5 trillion rubles ($145B) — 6.3% of GDP — into its war machine in 2025. That kind of “military Keynesianism” doesn’t build prosperity; it just keeps factories busy cranking out tanks.

Now the bill is coming due:

GDP growth slowed to just 1.4% in Q1 2025, with a 1.2% contraction after adjustment.

Inflation hit 10.2% in April.

The central bank is stuck at 21% interest rates to avoid collapse.

The budget deficit is swelling to 1.7% of GDP.

This is classic stagflation: fake war-driven growth hiding a shrinking economy and soaring prices. Putin can brag today — but Russia is already sliding into crisis.

Russia is in a self-inflicted “labor famine.” Since February 2022, 1–2 million workers have vanished from its economy:

The result: 73% of businesses are understaffed, while defense plants poach workers with salaries 40,000 rubles ($500) above civilian jobs.

The cracks are already visible:

And it’s not just Russia. Western companies that rely on Russian suppliers are watching production shrink in real time — proof that the war is choking not only Russia’s economy, but global supply chains too.

Because Russian inflation is already in your wallet — you just don’t see it yet.

Russia’s inflation hit 10.2% in April 2025, forcing interest rates up to 21%. That pain doesn’t stay inside Russia. To dodge sanctions, Russian firms burn $10–30 billion a year on shady commissions, and those costs get passed into the global price of oil, metals, fertilizer, and grain — the building blocks of everything from your phone to your food.

Here’s the hidden link: disrupted supply chains and higher transport/insurance costs drive up commodity prices everywhere. Russia makes critical inputs for semiconductors, aircraft parts, and agriculture. As Russia’s costs spiral, global alternatives rise too. Their inflation becomes your higher grocery bill and gas price.

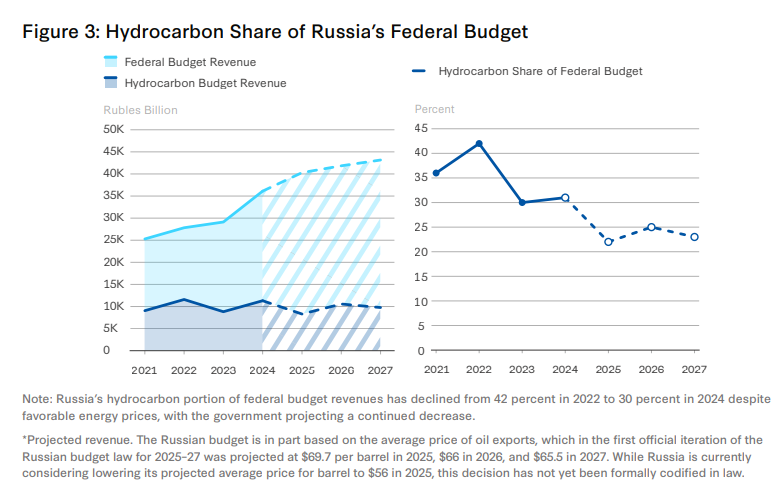

Russia’s oil revenues are collapsing in slow motion — and Putin’s war budget hangs on them more than he admits.

Oil made up 42% of the budget in 2022, but by 2024 it was down to 30% — even with high global prices. Sanctions forced Moscow to sell crude at a 15% discount, with shipping to India adding $10–15 per barrel.

Here’s the danger: Russia’s 2025 budget assumed $69.7 oil, but forecasts are already down to $56. In April 2025, Trump’s tariff threats sent Urals crude below $50. Every $10 drop = $10–15B lost revenue. If oil hit $30 again — as during COVID — Russia would lose as much money as it spends on the entire war.

Bottom line: Putin can brag about oil billions, but his lifeline is a knife-edge. One global shock, and the war chest collapses.

China is keeping Russia afloat — but that makes Moscow weaker, not stronger.

In 2024, Russia imported $115B in goods from China — 72% above pre-war levels. By 2023, 76% of battlefield-related deliveries came from China and Hong Kong. And now, 53% of all Russian imports are Chinese — meaning Beijing could cripple Russia’s war effort overnight by simply enforcing existing sanctions.

Despite talk of “yuanization,” Russia still can’t escape its need for dollars and euros. Meanwhile, China enjoys steep discounts on Russian oil, gas, and raw materials.

This isn’t partnership — it’s economic colonization. Beijing gains leverage, Moscow loses sovereignty. And for the West, the pressure point is clear: make China choose between Putin and global markets, and Russia’s lifeline snaps.

Russia’s banking system looks stable — but it’s built on quicksand.

Businesses owe $446B in loans, half to defense firms on subsidized rates of 5–6%, while everyone else pays 18–19%. At the same time, with interest rates at 21% and inflation near 9%, Russian savers get 11% real returns just by parking money in banks — deposits jumped 70% in 2024.

The entire system now depends on depositors’ trust. But here’s the trap: nearly half of government debt is floating-rate. If the central bank raises rates, debt costs explode; if it cuts, inflation spirals.

That’s the classic setup for a banking crisis — politically connected loans propped up by nervous savers. A shock — sanctions, a battlefield loss, or a ruble collapse — could spark a bank run and bring the system down in weeks.

Based on 2025 data, Russia can probably grind along for another 2–3 years under current sanctions — but only if nothing goes wrong.

What could speed up collapse:

Oil < $50/barrel: Already happened in April 2025, hitting budget revenues immediately

Stricter sanctions enforcement: Especially on China’s dual-use exports to Russia

Global recession: Trump’s tariff threats already rattled commodity markets this spring

Banking crisis: 21% interest rates keep savers in banks — until confidence cracks

Russia’s National Welfare Fund — the rainy-day reserve — dropped 24% in early 2025 to just ₽3.39T ($39B). At current burn rates, that cushion won’t last long; even the central bank has warned it could be emptied if oil collapses.

And remember: Russia is running its economy on war spending — defense outlays at 6%+ of GDP — the highest since the Cold War. That means Moscow’s “growth” depends on pouring money into weapons that get destroyed in Ukraine, not building lasting prosperity.

Bottom line: The system works — until it doesn’t. History says Russia might stagger on for 2–5 years, but unlike the USSR, today’s Russia can’t wall itself off. Global markets, sanctions, and war costs make it vulnerable to shocks that could accelerate the crash overnight.

For Ukraine and the West: the pressure is working. But it’s a test of stamina — keep it up, and Putin’s war economy will eventually break.

Russia’s collapse isn’t guaranteed — but the odds are rising. Labor shortages, runaway inflation, oil dependency, and record war spending are the same pressures that have broken other wartime economies.

Investors: steer clear of Russian commodities and watch for ripple effects in global supply chains.

Policymakers: sanctions are working, but only if pressure is steady and sustained — collapse takes years, not months.

Everyone else: Russia is more dangerous now, but less sustainable long term. The next 2–3 years will decide whether Putin’s war economy holds — or breaks.

© Doug Mills/The New York Times

After losing a key investor and facing production disruptions, AO Kronshtadt faces imminent bankruptcy. According to NV Biznes, 40 lawsuits totaling 626.3 million rubles ($7.76 million) have been filed against the company in just the past three months.

The financial collapse of the drone producer demonstrates how Western sanctions, combined with battlefield realities, are systematically undermining Moscow’s defense production capabilities.

Kronshtadt’s drones, including the Orion and Sirius systems sometimes compared to American Gray Eagles, provided crucial long-endurance surveillance and strike capabilities that Russia has deployed heavily in Ukraine since February 2022.

Russian media reports suggest the situation could lead to bankruptcy, as subcontractors who provided services or supplied products but have not been paid are “massively filing lawsuits to be included in the creditor registry,“ according to NV Biznes.

The debt claims come from different Russian technology companies and subcontractors, with the largest demands totaling hundreds of millions of rubles.

Military and aviation outlet War Wings Daily reports that by May 2025, total claims had already reached one billion rubles, with some sources estimating up to 1.5 billion rubles ($18.75 million) in debts over six months.

Kronshtadt’s last published financial data from 2020 showed losses of 3.6 billion rubles ($45 million), indicating long-standing financial struggles.

Kronshtadt has experienced financial difficulties for two years, with the crisis stemming from the 2022 withdrawal of AFK Sistema, the company’s strategic investor and main financing source. According to the NV Biznes report, this sharply worsened investment access and increased debt burden.

Without AFK Sistema’s financial backing, the company was left alone with cash flow gaps, while additional pressure came from sanctions and rising component costs.

US and EU sanctions cut off access to critical foreign-made components while inflating costs and creating production delays. Simultaneously, massive government orders placed heavy production demands precisely when supply chains faced maximum stress.

Ukrainian forces added a third pressure point, striking Kronshtadt’s Dubna production facility on 28 May 2025. Ukrainian drones hit the plant’s roof eight times, severely damaging industrial capacity at the facility producing systems central to Russia’s unmanned warfare strategy.

Nikolai Ryashin, general director of Rusdronport, suggested the company is headed toward collapse.

“The company will go the way of bankruptcy, so subcontractors are now rushing to file claims and get closer to the front of the line,” Ryashin said to Defence Blog, an independent defense and security news outlet.

As Kronshtadt struggles, Russia has sought alternative production methods.

In Khabarovsk, state-funded company Aero-hit built a plant with Chinese partners and became a major drone supplier for Russian operations in partially occupied Kherson Oblast. The facility produces multifunctional Veles drones and plans to reach 10,000 units monthly this year while expanding to more advanced models.

However, this doesn’t solve Kronshtadt’s problems. On the contrary, it might worsen them, as the state is finding alternatives to the ailing company.

The company’s collapse reveals a fundamental contradiction in Russia’s war economy: the state places massive orders but leaves manufacturers to struggle under sanctions pressure.

Despite heavy government investment, Western sanctions, Ukrainian strikes, and financial liabilities have pushed the enterprise past sustainability.

Whether Kronshtadt can be restructured or absorbed into another defense conglomerate remains uncertain. Still, the mounting lawsuits and expert assessments suggest Russia’s leading drone manufacturer is facing an inevitable path toward bankruptcy.

This development could significantly impact Moscow’s ability to maintain its drone-intensive warfare strategy in Ukraine.

© Brittany Greeson for The New York Times

A strike at the heart of Russia’s gas empire! Ukrainian forces hit a gas processing complex in Russia’s Ust-Luga, Leningrad Oblast, a strategic facility of the aggressor country in the Baltic region, according to Armiia TV.

“Ukrainian drones struck the gas processing complex of Novatek, the largest liquefied gas producer in Russia. The hit targeted the cryogenic fractionation unit for gas condensate/gas, which is the ‘heart’ of the facility’s technological processes,” the sources say.

This is the second successful attack on the Ust-Luga port in 2025, the first occurring in early January.

“Ust-Luga is Russia’s largest maritime hub in the Baltic. Shadow fleet, sanctioned oil — everything passes through there,” Lieutenant Andrii Kovalenko, head of the Center for Countering Disinformation at the National Security and Defense Council, stated.

Thanks to precise drone strikes, the operation disrupted the work of a key Russian logistics hub supplying liquefied gas and oil to external markets.

© Todd Heisler/The New York Times

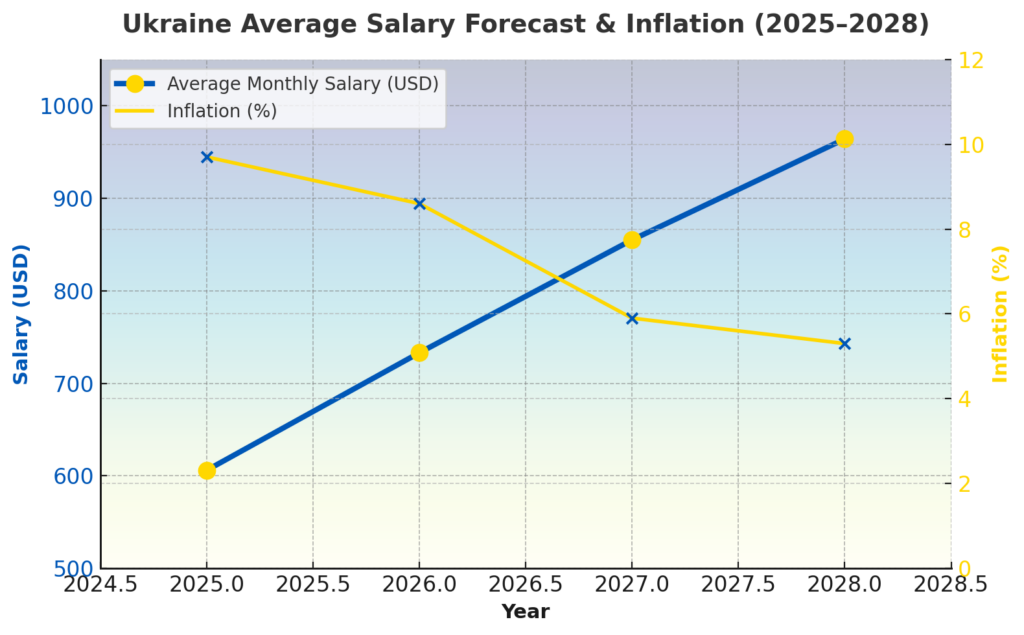

Ukraine’s government projects average monthly salaries will climb to nearly UAH 40,000 ($970) by 2028, almost doubling from current levels as the country signals economic resilience.

The forecast, released in Kyiv’s official socio-economic outlook for 2026-2028, shows wages rising from UAH 25,000 ($606) this year to UAH 39,800 ($964) by 2028 — a key metric for donors and investors evaluating Ukraine’s post-war recovery potential.

The projections serve dual purposes: demonstrating Ukraine’s economic viability to international backers while setting expectations for domestic consumption growth.

A consumer base earning nearly $1,000 monthly represents a compelling investment target for Western companies eyeing Ukraine’s eventual reconstruction.

“Given the high uncertainty, the Government’s forecast estimates are close to the forecasts of the European Commission and the IMF, which indicates a shared view of the key development trends,” the government stated in its forecast.

Ukraine’s wage progression timeline shows steady growth if stability holds:

The government projects inflation will ease from 8.6% in 2026 to 5.3% in 2028, meaning real purchasing power should grow alongside nominal wages.

The forecast presents two scenarios based on when hostilities end. Early stabilization in 2026 versus prolonged conflict until 2027 creates significant wage differentials — potentially thousands of hryvnia difference in workers’ pockets.

The current economic situation remains harsh for many Ukrainians. Millions remain displaced, key industrial sectors face ongoing Russian strikes, and many households rely on multiple income sources or remittances to cover rising costs.

The wage projections target international audiences who are considering Ukraine’s economic future. A market of 35 million educated, digitally connected consumers earning close to $1,000 monthly represents a substantial opportunity for consumer goods, housing, and services companies.

European Commission and IMF alignment on these projections strengthens Ukraine’s case for continued financial support and private investment, showing Western institutions view the country’s economic fundamentals as sound despite wartime pressures.

Higher wages matter for Ukraine’s broader recovery strategy. Increased domestic consumption drives tax revenue, supports local businesses, and demonstrates the economy’s capacity to sustain long-term growth — key factors in maintaining international confidence.

The forecast, which depends on wage growth, reflects Ukraine’s broader argument: this economy remains viable for investment and support, with a population still earning, spending, and building for the future despite the war.

Whether these projections materialize depends heavily on military developments and sustained international backing. But the government’s confidence in publishing them sends its signal — Ukraine is planning for economic success, not just survival.

© Kenny Holston/The New York Times

© Doug Mills/The New York Times

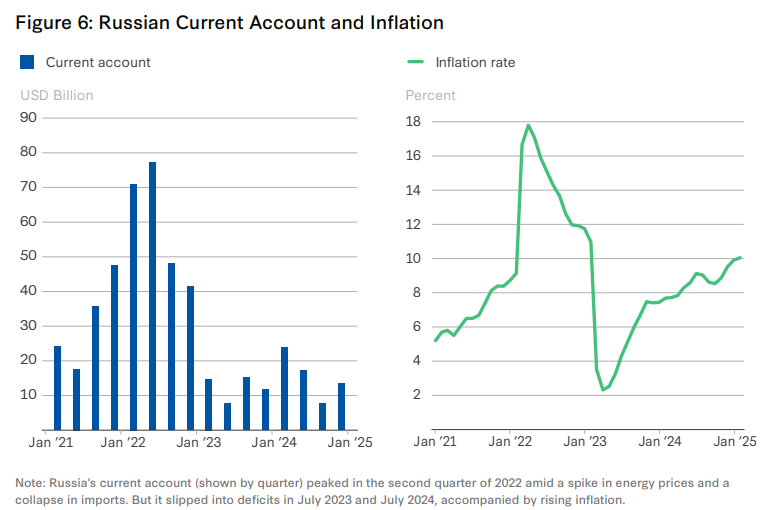

For months, Russia’s official inflation rate has hovered around 10%. In June, the Central Bank of Russia boasted that the rate had fallen to 9.4%, but it then dampened the celebration by reporting that expectations for inflation one year from now are 13% (which may well be the actual inflation rate today). Yet, on 25 July, the central bank dared to cut its very high interest rate, which has weakened growth and caused a severe credit crunch, from 20% to 18%.

True, Russia’s economy appeared surprisingly dynamic in 2023 and 2024, with the official growth rate reaching 4% each year. But this was largely because the Russian government revived dormant Soviet military enterprises beyond the Ural Mountains. Moreover, real growth figures may have been exaggerated because some inflation was hidden by state-owned enterprises selling their goods to the state at administered prices.

In any case, official growth has fallen this year, probably to 1.4% in the first half of 2025. Since October 2024, the Kremlin itself has begun to report that Russia is experiencing stagflation – a message that was reinforced at the annual St. Petersburg International Economic Forum in June.

Improvement is unlikely. The country’s financial reserves are running out, energy revenues are declining, and there are increasingly severe shortages of labor and imported technology. All are linked to the war and Western sanctions.

Since 2022, Russia has had an annual budget deficit of about 2% of GDP, implying that it needs $40 billion each year to close the gap. But owing to Western financial sanctions, Russia has had virtually no access to international financing since 2014.

Not even China dares to finance the Russian state openly, for fear of secondary sanctions.

(Indeed, two small Chinese banks were just sanctioned by the European Union for such sins.) So, Russia must make do with the liquid financial resources held in its National Wealth Fund. Having fallen from $135 billion in January 2022 to $35 billion by May 2025, these are set to run out in the second half of this year.

Traditionally, half of Russia’s federal revenues have come from energy exports, which used to account for two-thirds of its total exports. But in the face of Western sanctions, Russia’s total exports have slumped, falling by 27%, from $592 billion to $433 billion, between 2022 and 2024.

The federal budget for 2025 assumed an oil price of $70 per barrel, but oil is now hovering closer to the Western price cap of $60 per barrel, and the EU has just set a ceiling of $47.6 per barrel for the Russian oil that it still purchases. In addition, the West has sanctioned nearly 600 Russian “shadow fleet” tankers, which will reduce Russian federal revenues by at least 1% of GDP.

Against this backdrop, the Kremlin has announced that while it intends to spend 37% of its federal budget – $195 billion (7.2% of GDP) – on national defense and security this year, it must cut federal expenditures from 20% of GDP to about 17%. But since the government has already cut non-military expenditures to a minimum, it claims that it will reduce its military expenditures by some unspecified amount in 2026.

Reducing military expenditures at the height of a war is rarely an auspicious signal. As the commentator Igor Sushko points out, “The Confederacy did this in 1863-1865 (American Civil War), Germany in 1917-1918 (WWI), Japan in 1944-1945 (WW2),” and the outcome every time was “total military defeat.”

Of course, actual economic strength is not the issue. Ukraine spends about $100 billion per year on its defense, which amounts to 50% of its GDP, but no one bothers to question this, because for Ukrainians, the war is existential. Ukraine would not survive if the war was lost.

By contrast, Russia spends only 7% of its GDP on the war, but this is a war of Putin’s choice. It is not existential for Russia, only for Putin.

If he had a popular mandate, Russia could spend much more on the war. But he apparently does not think his popularity could withstand devoting much more of the budget to the effort.

Meanwhile, it is increasingly clear that something else is rotten in Russia besides the economy. Russia has fallen to 154th place out of 180 countries on Transparency International’s authoritative Corruption Perceptions Index, while Ukraine is in 105th place. Since the start of the war, a dozen or so senior Russian energy managers have fallen out of windows.

And more recently, former Deputy Defense Minister Timur Ivanov was sentenced to no less than 13 years in prison for corruption; Transportation Minister Roman Starovoit allegedly committed suicide just hours after Putin fired him; and a gold-mining billionaire was arrested, and his company was nationalized to help the treasury.

These were high officials. Ivanov was a top protégé of former Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu, and Starovoit was the right-hand man of Putin’s close friend Arkady Rotenberg. Such developments are clear signs of Russia’s economic instability.

Compounding the financial pain is an extreme labor shortage, especially of qualified workers.

Officially, unemployment stands at only 2%, but that is partly because many Russians have left. Since the start of the war, and especially after Putin attempted a minor mobilization in 2022, approximately one million people fled the country, including many young, well-educated men.

He has not dared to pursue another mobilization since.

Now, labor scarcities are holding back production and driving up wages, while Western export controls limit Russia’s supply of high-tech goods (though Chinese supplies have mitigated the impact).

Russia’s economy is fast approaching a fiscal crunch that will encumber its war effort. Though that may not be enough to compel Putin to seek peace, it does suggest that the walls are closing in on him.

Editor’s note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press’ editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

Canada joins EU and UK to lower the Russian oil price cap to $47.60 in a move aimed at cutting Kremlin revenues while avoiding shocks to global markets. The change, due in early September, leaves Japan and the US as the only G7 members not adopting the reduced limit.

On 8 August, the Department of Finance of Canada confirmed Ottawa will match the European Union and United Kingdom in reducing the price cap on seaborne Russian-origin crude oil from $60 to $47.60 per barrel. The measure is part of the G7-led sanctions mechanism introduced in December 2022 to restrict Moscow’s war funding. The coalition also includes Australia and New Zealand.

Finance Minister François-Philippe Champagne said the cut would increase economic pressure on Russia and limit a crucial source of funding for its war in Ukraine. Foreign Minister Anita Anand stressed Canada’s commitment to applying sustained pressure on Moscow. Kyiv has pressed for an even lower $30 limit.

Most G7 members will introduce the lower cap in September. Japan and the US have not signed on, but Canada remains part of the Price Cap Coalition and may follow future reductions agreed within the group.

According to preliminary data from the Finance Ministry cited by The Moscow Times, the deficit increased by 1.2 trillion rubles ($15 billion) in July alone, and expenditures jumped to 3.9 trillion rubles ($49 billion).

This data shows Russia’s war machine consuming the state itself. Unlike previous conflicts, Moscow can’t fund this war indefinitely — and Western allies now have concrete proof that sustained pressure works.

The new figures reveal a grim picture of stagnation, overspending, and war-at-all-costs priorities. According to Reuters, government spending rose more than 20% in the first seven months of 2025, while revenues grew just 2.8%. That gap is mainly driven by ballooning military costs.

What makes the alarm even more telling is that the warning comes directly from Russia’s central bank: it now forecasts zero growth by December, down from 4.5% last year.

So far this year, Russia has spent 25.2 trillion rubles ($320 billion) — a staggering increase from pre-war spending levels when the annual federal budget totaled around $220 billion in 2021.

As Bloomberg reports, signs of crisis are now visible across different sectors, as coal mining companies suffer losses, oil, gas, and metallurgy companies see a decline in profits. The automotive industry significantly cuts production due to weak demand.

Productivity in civilian sectors is falling fast. The Moscow Times reported in July that Russian car makers have all shifted to a four-day work week to preserve existing jobs due to diminishing demand, high interest rates, and a lack of affordable financing tools for buyers.

Russia’s aviation industry, once a symbol of national pride, has delivered just one of 15 promised passenger aircraft this year.

Sanctions, oil price caps, and labor shortages are eroding Russia’s economic foundation — yet Moscow shows no intention of scaling back its invasion. A recession with consequences far beyond Russia’s borders now looms.

The signs are clear: Western sanctions, shifting energy markets, and export controls are having an impact. But they’re not enough on their own. The Kremlin is willing to sacrifice every civilian sector to keep the war machine running.

That’s why Ukraine’s battlefield resilience — and sustained Western support — remain essential. Economic pressure may hurt Russia, but it won’t stop the war on its own.

For Western policymakers, these numbers prove that economic pressure is working, but they also show why military aid remains crucial to finish what sanctions started. Russia’s budget crisis gives Ukraine a strategic window, but only if allies simultaneously maintain economic and military pressure.

Already 25% over the annual target, with 5 months to go.

Factories, cars, aviation hit hard.

Oil price caps, export controls, labor shortages.

Economic pressure works — but won’t stop the war alone.

Thanks to your incredible support, we’ve raised 70% of our funding goal to launch a platform connecting Ukraine’s defense tech with the world – David vs. Goliath defense blog. It will support Ukrainian engineers who are creating innovative battlefield solutions and we are inviting you to join us on the journey.

Our platform will showcase the Ukrainian defense tech underdogs who are Ukraine’s hope to win in the war against Russia, giving them the much-needed visibility to connect them with crucial expertise, funding, and international support.

We’re one final push away from making this platform a reality.

The European Commission is discussing with EU member states various options to cover Ukraine's budget deficit for next year, which could range from $8 billion to $19 billion, the Financial Times reported on July 8.

International partners have provided Ukraine with over $39 billion for its wartime economy so far this year, Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal announced.

The financial hole in Ukraine's budget is linked to reduced U.S. support and the lack of prospects for a swift ceasefire with Russia that Europe had hoped for, the Financial Times reported.

A senior EU official told the publication that many of Ukraine's partners had previously counted on a peace deal in 2025, but are now forced to revise their funding plans.

This includes the European Commission, which has already adjusted spending from Ukraine-related funding streams.

Without support from Western partners, Kyiv would face a budget deficit of $19 billion in 2026, according to the Financial Times. However, even if additional international financing for the wartime economy can be secured, a gap of at least $8 billion would remain.

To support Ukraine's budget, Europe is considering providing military aid in the form of off-budget grants that would be recorded separately as external transfers but would count toward NATO member countries' national defense spending targets.

One EU diplomat told the Financial Times that military support for Ukraine is viewed as a contribution to the defense of all of Europe.

In a document for G7 countries reviewed by Financial Times, Kyiv proposed that European allies co-finance Ukrainian forces, framing this as a service to strengthen continental security.

Other support options under discussion include potentially accelerating payments from the existing $50 billion G7 loan program and reinvesting frozen Russian assets in higher-yield financial instruments that the EU allocated to help service the debt.

According to the Financial Times, two sources confirmed that the commission planned to discuss these options with EU finance ministers on July 8.

The funding issue will also be raised at the Ukraine Recovery Conference in Rome on July 10-11, dedicated to Ukraine's reconstruction needs. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen will attend the event.

Russia's economy, which defied initial sanctions and saw growth propelled by massive military spending and robust oil exports, is now showing significant signs of a downturn.

Recent economic indicators are flashing red, with manufacturing activity declining, consumer spending tightening, and inflation remaining stubbornly high, straining the national budget, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported on July 4.

Russian officials are openly acknowledging the risks of a recession. Economy Minister Maxim Reshetnikov warned last month that Russia was on the "verge of a recession," while Finance Minister Anton Siluanov described the situation as a "perfect storm." Companies, from agricultural machinery producers to furniture makers, are reducing output. The central bank announced on July 3 it would debate cutting its benchmark interest rate later this month, following a reduction in June.

While analysts suggest this economic sputtering is unlikely to immediately alter President Vladimir Putin’s war objectives—as his focus on "neutering Ukraine" overrides broader economic concerns—it exposes the limits of his war economy.

The slowdown indicates that Western sanctions, though not a knockout blow, are increasingly taking a toll. If sanctions intensify further or global oil prices fall, Russia’s economy could face more severe instability. This downturn undermines Putin's strategic bet that Russia can financially outlast Ukraine and its Western allies, suggesting Moscow may struggle to finance the war indefinitely.

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

Experts warn that Russia's economic growth model, overly reliant on military spending, is unsustainable and necessitates a contraction of civilian economic capacities to free up workers for the war machine, which is not a viable long-term strategy. Putin recently dismissed suggestions that the war is stifling the economy, echoing Mark Twain by stating reports of its death "are greatly exaggerated." However, he also cautioned that a recession or stagflation "should not be allowed under any circumstances."

After a brief recession in 2022, military spending, which accounts for over 6% of gross domestic product this year (the highest since Soviet times) and approximately 40% of total government spending, had propped up Russia’s economy and blunted the impact of Western sanctions. Russia’s ability to reroute oil exports to China and Beijing’s support with electronics and machinery provided additional economic stimulus. This created an economic paradox: the most sanctioned major economy was, for a period, growing faster than many advanced economies.

However, this military spending "sugar rush" fueled runaway inflation, compelling the central bank to raise interest rates to a record 21% to try and tame it. Higher interest rates increased borrowing costs for businesses, curbing investment, expansion plans, and squeezing profits. The economic comedown has already begun.

Official data shows Russian GDP growth slowed to 1.4% in the first quarter compared to a year earlier, down significantly from 4.5% in the fourth quarter of 2024. S&P Global’s purchasing managers’ index indicated Russia’s manufacturing sector contracted at its sharpest rate in over three years in June, and new car sales dropped nearly 30% year-over-year in June.

Businesses across Russia are feeling the effects, according to the WSJ. Rostselmash, the country’s largest producer of agricultural machinery, announced in May it would cut production and investment, and pull forward mandatory annual leave for its 15,000 employees due to a lack of demand. In Siberia, electricity grid operator Rosseti Sibir stated it was on the verge of bankruptcy due to high debt, halting investments and proposing tariff hikes for industrial users.

While some analysts argue the Russian banking system remains stable, others warn of increasing instability. A recent report by the Washington, D.C.-based Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) highlighted risks from a government decision to control war-related lending at major Russian banks. The state could direct banks to offer preferential loans, potentially forcing the government to absorb losses if high interest rates prevent companies from meeting obligations.

The Moscow-based Center for Macroeconomic Analysis and Short-Term Forecasting also assessed in May that the risk of a protracted systemic banking crisis in 2026 was "moderate" and growing.

These economic challenges intensify pressure on the Kremlin by reducing its financial capacity to fund its war in Ukraine. The government has operated with a budget deficit throughout the war and projects this will continue for at least two more years. This fiscal strain could provide an opening for Western nations to implement more powerful sanctions.

Falling oil prices present another significant risk for Russia, as energy sales account for about a third of its budget revenues. The price of Russian crude has consistently remained below the level assumed in this year’s budget, and Russia’s oil-and-gas revenue in June fell to its lowest level since January 2023, according to Finance Ministry data.

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy

The Kyiv IndependentTim Zadorozhnyy