Sweden sends Ukraine billions in military aid—and every armored vehicle. Gripen jets? Ask NATO

For over two centuries, Sweden was a nation defined by military neutrality. It avoided entanglement in great wars, instead cultivating a reputation as a mediator, peace broker, and humanitarian power. Yet Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 transformed Sweden’s strategic outlook almost overnight.

Within just a few years, Stockholm abandoned neutrality, joined NATO, and emerged as one of Kyiv’s most reliable defense and reconstruction partners. This is a historic shift: while Ukraine continues its long struggle to secure NATO membership, Sweden’s accession and its unprecedented support for Kyiv carry both symbolic and practical weight.

In collaboration with the Dnistrianskyi Center, Euromaidan Press presents this English-language adaptation of Dariia Cherniavska’s analysis on Sweden’s role in Ukraine’s defense, recovery, and pursuit of justice.

From neutrality to NATO

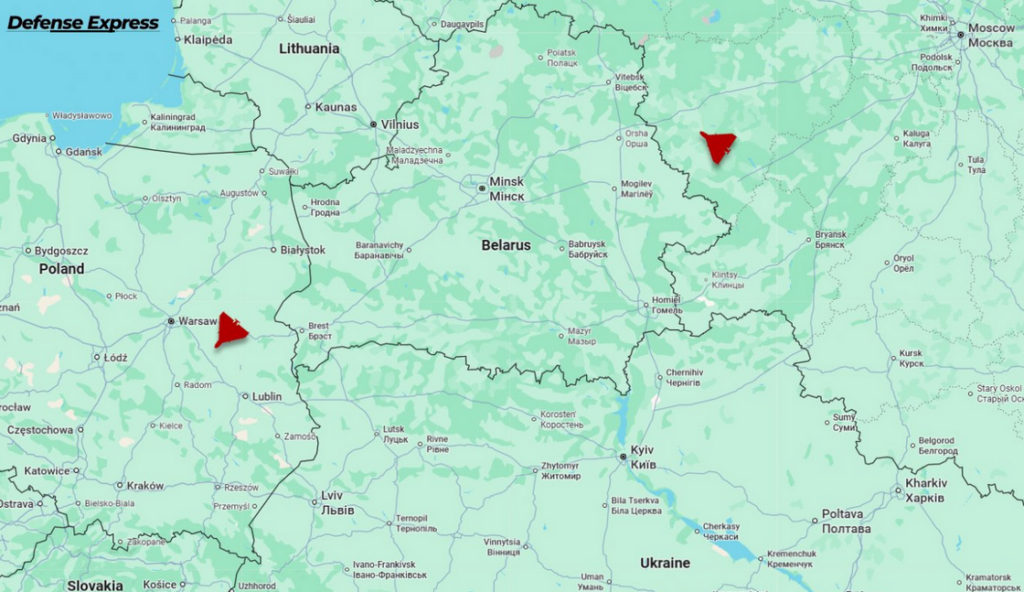

Russia’s aggression redrew Europe’s security map. Alongside Finland, Sweden applied to join NATO in 2022, breaking with its centuries-old neutrality. By March 2024, Stockholm became NATO’s 32nd member.

For Sweden, NATO membership offered the ultimate guarantee: collective defense under Article 5. For Ukraine, it meant new, powerful allies along Russia’s northern flank—even though Kyiv itself still stands outside the Alliance despite years of open aspiration.

The symbolism is clear: neutrality is no longer a shield, and solidarity has become survival.

Sweden’s pledge: a structured, long-term commitment

Sweden’s support for Ukraine is remarkable not just for its scale but also for its design. In 2024, Stockholm committed €6.5 billion in military support between 2024 and 2026—a massive pledge for a country of just 10 million people.

Unlike one-off donations, this funding is structured to guarantee predictability. Ukraine knows what to expect, quarter by quarter, allowing it to plan defense procurement and operations. In Europe, this places Sweden among the very top donors relative to its population and GDP.

Sweden–Ukraine security pact explained

On 31 May 2024, Sweden and Ukraine signed a 10-year Security Cooperation Agreement. This was the 13th pact under the G7 Joint Declaration of Support for Ukraine, and among the most ambitious. By May 2025, Kyiv had signed 29 such agreements, yet the Swedish deal stands out for both symbolic and practical reasons.

The agreement covers:

- Military support, including predictable weapons transfers and training.

- Cybersecurity cooperation.

- Energy resilience projects.

- Justice initiatives and humanitarian recovery.

For Ukraine, locked in a war of attrition, predictability of aid is nearly as valuable as its volume. Stockholm’s 10-year commitment sends a message that Ukraine will not be left alone.

Sweden’s military aid to Ukraine

Since 2022, Sweden has become one of the most active suppliers of weapons to Ukraine. Its military aid ranges from cutting-edge artillery systems to armored vehicles, drones, and naval craft.

What weapons has Sweden sent to Ukraine?

Stockholm’s aid packages have included:

- Archer self-propelled howitzers and ARTHUR counter-battery radars.

- CV90 infantry fighting vehicles, co-produced with Ukraine.

- Combat Boat 90 vessels for river and coastal defense.

- Thousands of anti-tank weapons and drones.

- RBS 70 man-portable air defense systems.

- AT4 grenade launchers and ammunition.

- At least 1,500 TOW anti-tank missiles.

- Entire fleet of Pansarbandvagn 302 armored vehicles.

- Two Saab 340 AEW&C (ASC 890) airborne radar aircraft (still pending delivery as of mid-2025).

Delays and cooperation mechanisms

Not every pledged item has arrived. For example, Ukraine is still awaiting the ASC 890 radar planes, first announced in May 2024. Sweden explained the delay stems from integration work with partner states to ensure compatibility with F-16 fighters.

Meanwhile, Sweden has actively supported multinational defense coalitions, most notably the Drone Coalition. Together with the UK, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Latvia, Stockholm co-financed the production of 30,000 drones worth $55 million. Within its 18th and 19th aid packages alone, Sweden allocated over $35 million to drones.

Artillery is another focus. In January 2025, Sweden signed contracts to supply Ukraine with 18 new Archer howitzers and five ARTHUR radars worth nearly $300 million. In May 2025, it pledged an additional $60 million for artillery shells, including through the Czech initiative to procure 155mm ammunition.

The Gripen question

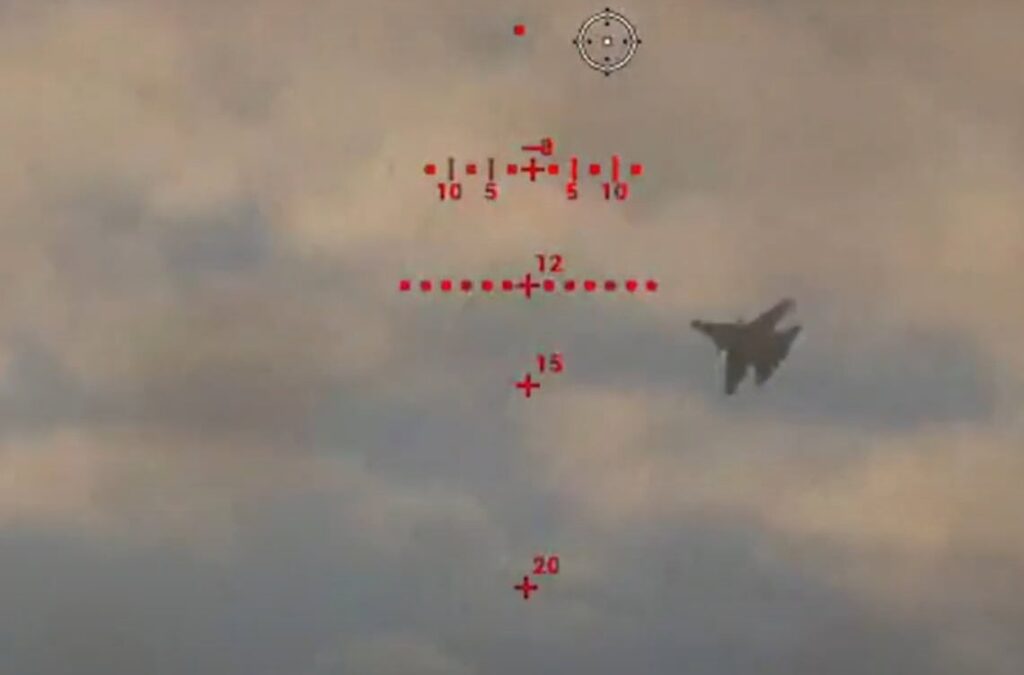

One of the most discussed possibilities in Swedish aid has been the Saab JAS 39 Gripen fighter jet. The Gripen is valued for its unique flexibility: it can operate from short roadways instead of relying solely on airbases, a critical advantage for Ukraine where runways are prime targets. Light, cost-effective, and interoperable with NATO systems, many analysts consider it ideally suited for Ukraine’s conditions.

Yet, despite pilot training and political debate, Sweden has paused any transfer of Gripens. NATO partners have urged Stockholm to prioritize the delivery of F-16s, ensuring consistency across Ukraine’s future fleet. For now, Gripens remain out of reach — a reminder that even among allies, strategic reasoning sometimes outweighs battlefield logic.

Training Ukraine’s forces

Military hardware is only as powerful as the soldiers who operate it. Sweden made training a core pillar of its support, ensuring Ukrainian personnel can master advanced Western systems.

Training has covered:

- CV90 infantry fighting vehicles – complex platforms requiring highly trained crews.

- Archer howitzers – precision artillery that demands technical and logistical expertise.

- RBS 70 air-defense systems – crucial for intercepting drones and missiles.

Beyond skills transfer, this training builds NATO interoperability. Ukrainian forces learn not only how to operate the systems but also how to integrate with Western command and logistics standards. This accelerates Ukraine’s eventual path toward NATO integration.

Industrial cooperation: building Ukraine’s defense future

Perhaps the most forward-looking element of Swedish support is industrial cooperation. Rather than just donating weapons, Stockholm is helping Ukraine build its own defense industry capacity.

The landmark project is the co-production of CV90 infantry fighting vehicles. Through agreements with BAE Systems Hägglunds, Ukraine is establishing assembly lines, maintenance hubs, and training centers on its own soil.

This model offers three benefits:

- Rapid battlefield repairs — damaged vehicles can be fixed locally.

- Jobs and technology transfer — boosting Ukraine’s defense workforce and economy.

- Integration into NATO supply chains — ensuring long-term compatibility.

Sweden’s industrial vision goes beyond armored vehicles. Its role in the Drone Coalition encourages Ukrainian manufacturers to scale unmanned systems. Future cooperation could also cover artillery production, radar technologies, and cybersecurity, positioning Ukraine as a hub of European defense innovation.

Non-military aid: humanitarian, energy, and sanctions

Sweden’s support for Ukraine has never been limited to weapons. Civilian and humanitarian assistance forms a critical second pillar of Stockholm’s strategy. By early 2025, Sweden had provided roughly $1.2 billion in non-military aid, complementing the billions already committed for defense.

This funding has taken many forms:

- Humanitarian relief and reconstruction — about $300 million directed toward rebuilding infrastructure, repairing homes, and supporting displaced families.

- Emergency response and crisis management — more than $220 million for humanitarian organizations, healthcare, and local authorities working under wartime conditions.

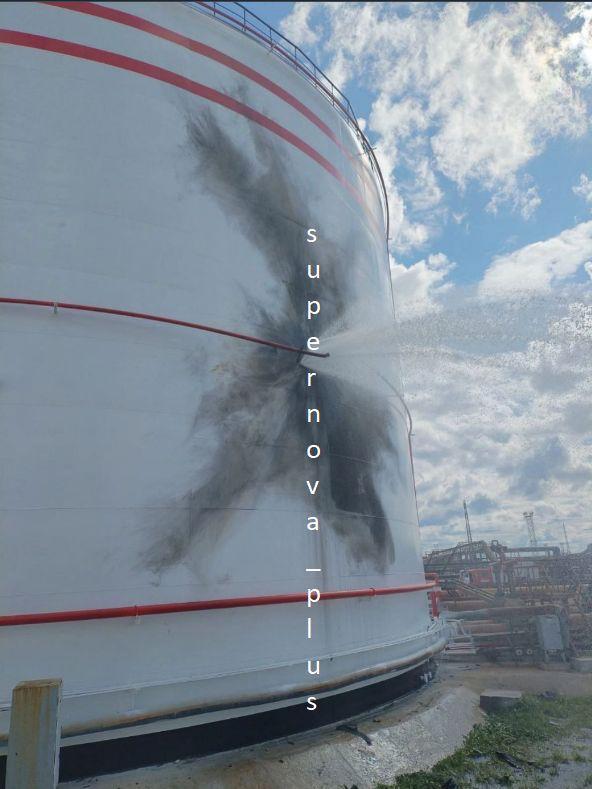

- Energy resilience — over $140 million to Ukraine’s Energy Support Fund, helping restore critical power facilities regularly targeted by Russian strikes.

- Special initiatives — including demining programs, medical training, and $9.5 million for the “Grain from Ukraine” initiative to deliver grain to food-insecure countries.

In March 2025 alone, Stockholm announced an additional $138 million civilian aid package focused on reconstruction, demining, and strengthening Ukraine’s health sector.

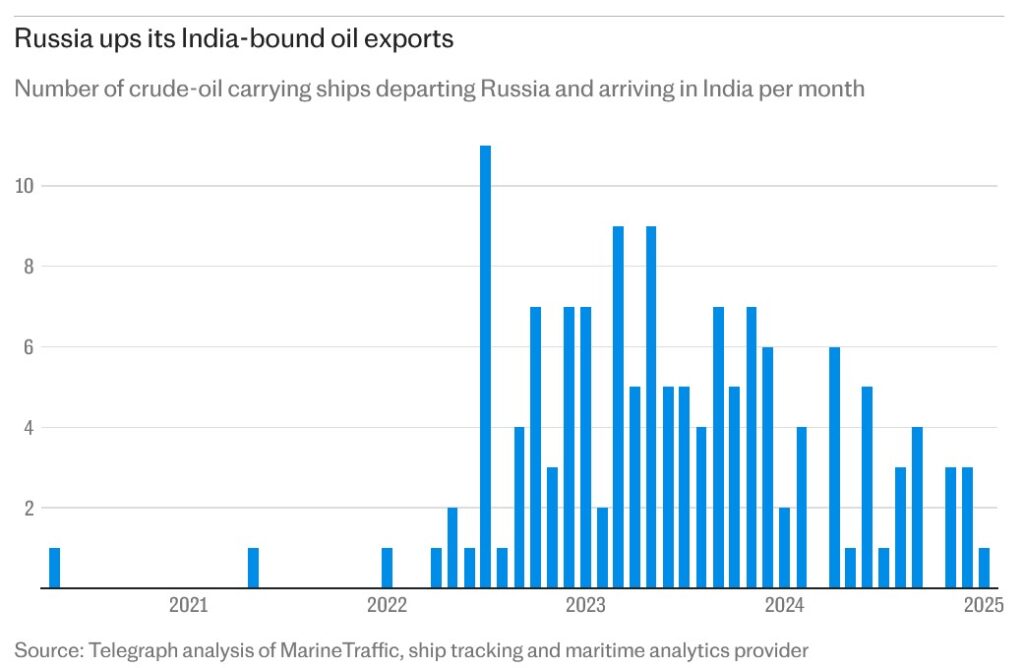

Beyond funding, Sweden has been a strong advocate for EU sanctions against Russia, pushing for tighter restrictions on critical technologies and energy revenues. Together, these measures show that Sweden views Ukraine’s survival not only as a military struggle but as a fight for the resilience of its society and economy.

Symbolism and strategy

Sweden’s transformation carries both symbolic and strategic meaning.

Symbolically, a nation that long prided itself on neutrality has chosen sides in Europe’s defining war of the 21st century. For Ukraine, this sends a powerful signal: neutrality is not an option when aggression threatens the foundations of European security.

Strategically, Sweden’s contributions fill key gaps:

- Air defense and situational awareness (ASC 890 planes, RBS 70 systems).

- Mobile firepower (Archer howitzers, CV90s, AT4s).

- Maritime defense (Combat Boat 90s).

- Technological edge (drones, radar systems, industrial partnerships).

Coupled with humanitarian aid and demining, Sweden’s support touches nearly every aspect of Ukraine’s survival and recovery.

The road ahead

As the war continues, Ukraine’s survival depends on sustained partnerships. Sweden has shown it is not just reacting to crises but planning for the long term:

- 10-year security pact.

- €6.5 billion structured support program.

- Industrial cooperation projects that outlast the war.

For Ukraine, Sweden provides more than weapons: it offers predictability, partnership, and proof that Europe’s security is indivisible.

Why Sweden’s support matters

Sweden’s military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine marks one of the most dramatic foreign policy transformations in modern Europe. From neutrality to NATO membership, from peace diplomacy to arms co-production, Stockholm has taken steps that would have seemed unthinkable just a decade ago.

For Ukraine, this partnership delivers more than immediate aid. It lays the foundations for a resilient defense industry, NATO interoperability, and eventual recovery from war.

For Europe, it demonstrates that even long-neutral nations can be compelled to act when aggression strikes at the heart of the continent’s security.

2 Russian soldiers fell instantly.

2 Russian soldiers fell instantly.

ABC

ABC