Can Europe replace US Patriots for Ukraine as its “daddy” in Washington steps back?

“We’ve got a global front that matters to America.” State Department spokeswoman Tammy Bruce delivered that message during a 2 July briefing, as the Pentagon confirmed suspension of critical weapons shipments to Ukraine, including Patriot air defense missiles that protect civilians from constant Russian bombardment.

Bruce also noted that Washington expects European partners to “chime in” more substantially because of “the fronts that we’re always dealing with around the world.”

For Ukraine, the timing couldn’t be more alarming. Officials in Kyiv are scrambling to understand why US shipments already staged in Poland were abruptly halted, requesting clarification and a phone call between President Zelenskyy and President Trump.

The decision also sparked concern in Europe. French President Emmanuel Macron held his first phone conversation with Vladimir Putin since 2022 this week—a two-hour discussion that yielded no breakthrough but may reflect growing anxiety about America’s shifting priorities.

Dr. Frank Ledwidge, a senior lecturer in War Studies at Portsmouth University in the UK, told Euromaidan Press that these developments mark the inevitable consequence of Europe’s long reliance on US military support.

“Europe has been living a big holiday,” Ledwidge explains, “and now we have to pay for it.”

But while European governments may now face a geopolitical reckoning, it is Ukrainians who are paying the real price, dying under Russian missiles, bombs, and drones. Euromaidan Press set out to examine whether Europe can finally deliver on its promises to “stand with Ukraine” and provide the air defense systems needed to help the country survive.

US halts Ukraine aid without warning

The weapons suspension caught even senior officials off guard—Congress members, State Department officials, and European allies learned about it from news reports, according to Politico.

Pentagon policy chief Elbridge Colby appears to have driven the decision largely alone. He led an internal review that found US arsenals of artillery rounds, air defense missiles, and precision munitions had dropped to concerning levels. But here’s what didn’t happen: coordination with the rest of the government.

Who got blindsided? The State Department learned from media reports. The US embassy in Kyiv wasn’t consulted. Ukraine envoy Keith Kellogg’s team had no advance notice, Politico reports.

Amid the chaos, the halted weapons represent Ukraine’s survival kit: Patriot interceptor missiles, 155mm artillery shells, HIMARS rockets, Stinger missiles, and Hellfire missiles. More than two dozen Patriot PAC-3 missiles and over 90 AIM air-to-air missiles were among weapons recalled from Poland, according to the Wall Street Journal.

For Ledwidge, this decision reflects America’s strategic rebalancing rather than vindictiveness toward Ukraine.

“The overriding strategic priority for the United States Armed Forces is the Western Pacific,” he notes. “The most effective systems that the Americans currently have are the ones most needed in Ukraine, but they would be very much in demand in the South China Sea and in any Taiwan contingency.”

But the Pacific isn’t America’s only concern. The US has already redirected 20,000 air defense missiles from Ukraine to Middle East operations against Iranian targets and Houthi forces in Yemen—part of what State Department spokeswoman Bruce called America’s “global front.”

Europe’s air defenses fall short

White House Deputy Press Secretary Anna Kelly defended the suspension: “The strength of the United States Armed Forces remains unquestioned—just ask Iran.” She referenced recent US military operations against Iranian nuclear sites.

But does the decision contradict that claim? If American military strength were truly unquestioned, why suspend weapons to a critical ally during wartime?

Ledwidge sees a fundamental paradox. “The West has been projecting this idea of strength when, in fact, much of that strength is illusory. The American armed forces do look like a very large and powerful force, and they are. However, they are very broad but in some ways not very deep.”

This depth problem extends across the Atlantic.

“Europe does not have sufficient air defense systems to defend itself, let alone give to Ukraine,” Ledwidge observes.

The United Kingdom exemplifies this weakness: “We have no Patriots, some ship-based equivalent missiles but no land-based launchers, and no missile defense system at all in Britain.”

The production constraints are stark. Only 20-30 Patriot missiles can be manufactured monthly, while far more are consumed in Ukraine and Middle East operations.

“These systems take a very long time to develop and build up large stocks,” Ledwidge notes, highlighting the gap between political promises and industrial reality.

Trump pushes NATO to pay up

Europe’s predicament stems from decades of what NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte embarrassingly called relying on America as “Daddy.” Trump’s “America First” policy has shattered this arrangement.

The doctrine prioritizes American interests and capabilities above alliance commitments, demanding that allies shoulder greater responsibility for their own security rather than relying on US guarantees.

At the recent NATO summit in The Hague, Trump pushed European nations to spend 5% of GDP on defense, which is a target that doubles most current commitments.

Geography explains European divisions. Eastern European nations—Poland, the Baltic states, Finland—have taken Russian threats seriously. Poland began rearming a decade ago.

“Only now are we seeing the weapons coming through,” Ledwidge notes, highlighting the long lead times for military modernization.

By contrast, southwestern European countries remain hesitant to embrace substantial defense spending increases. Why should they worry? “Spain and its leaders don’t really face Russia as a problem,” Ledwidge observes.

While Poland builds serious deterrent capabilities and the Baltic states invest heavily despite their small size, major Western European powers continue to prioritize social spending over military readiness.

Here’s the catch: “For the last 30 years, we’ve been paying heavily for social security and other priorities while America has underwritten our defenses. This is why Britain doesn’t have any serious air and missile defense system—why should we when the Americans will defend us?”

The comfortable arrangement is over. European leaders now show what Ledwidge describes as “rather fearful expressions.” Even Macron’s outreach to Putin represents choosing “from a few very poor options available to him” as France lacks military leverage to dictate terms to Russia.

Can decades of underinvestment be reversed quickly?

“You’re trying to make up for 30 years of underinvestment, and that will take much more effort than we’ve seen so far,” Ledwidge warns.

Russia’s allies deliver, Europe stalls

While Europe struggles with defense spending commitments and America suspends weapons shipments, Russia has built a robust support network.

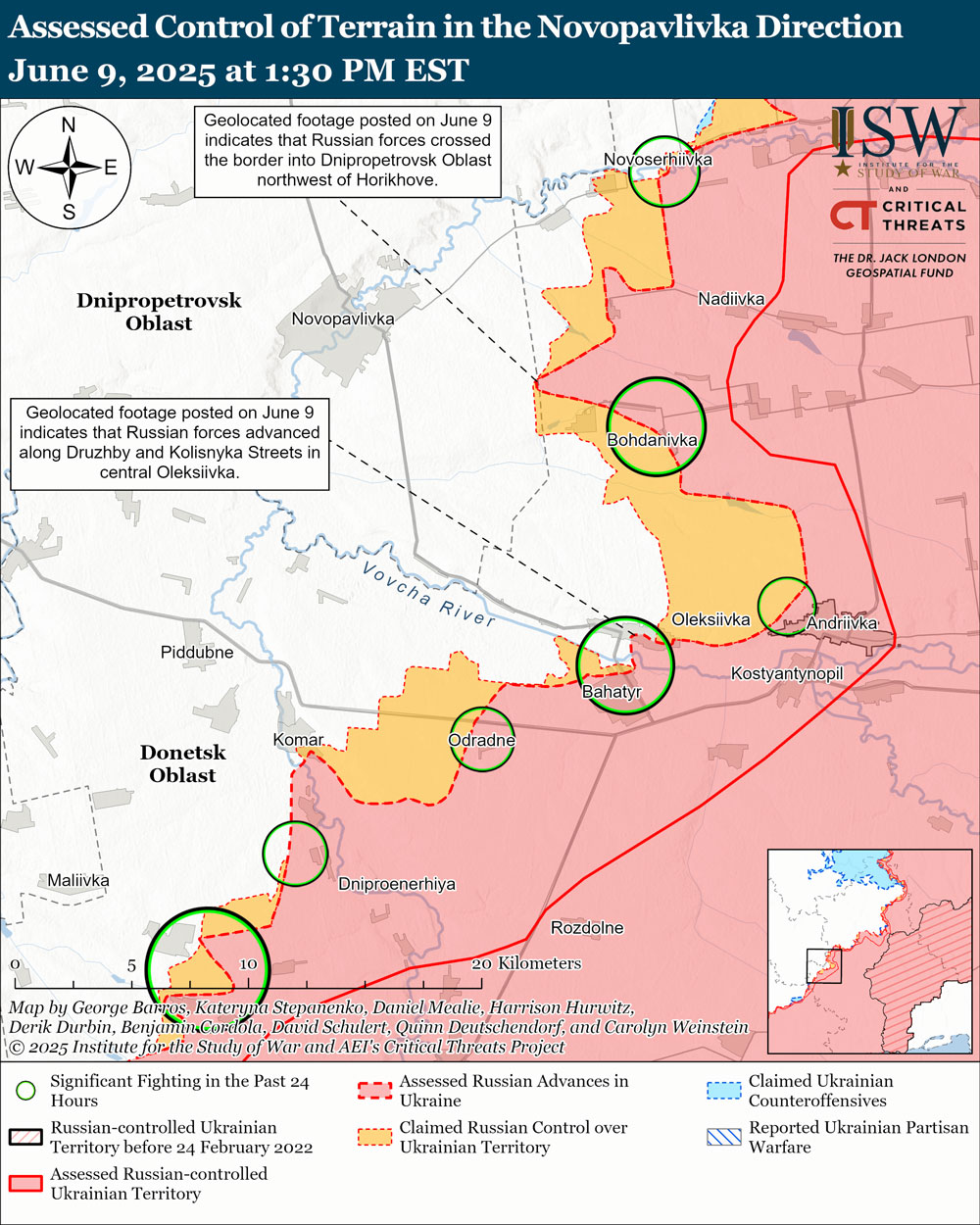

North Korea plans to send an additional 25,000 to 30,000 troops to assist Russia, tripling its military commitment from the original 11,000 soldiers deployed in November 2024 to Russia’s Kursk Oblast. Over 6,000 North Korean troops have already been killed, wounded, or gone missing in heavy frontline fighting.

Additionally, North Korea has supplied Russia with millions of artillery shells, along with missiles, long-range rocket systems, self-propelled howitzers, and short-range missile systems.

China’s role proves more substantial despite official denials. Chinese manufacturers supply Russia with 80% of critical electronics for Russian drones, according to Ukraine’s Foreign Intelligence Service. Beijing provides machine tools, special chemicals, gunpowder, and components directly to 20 Russian military factories.

“They use so-called shell companies, change names, do everything to avoid being subject to export control,” Ukrainian intelligence explains.

The production numbers tell the story.

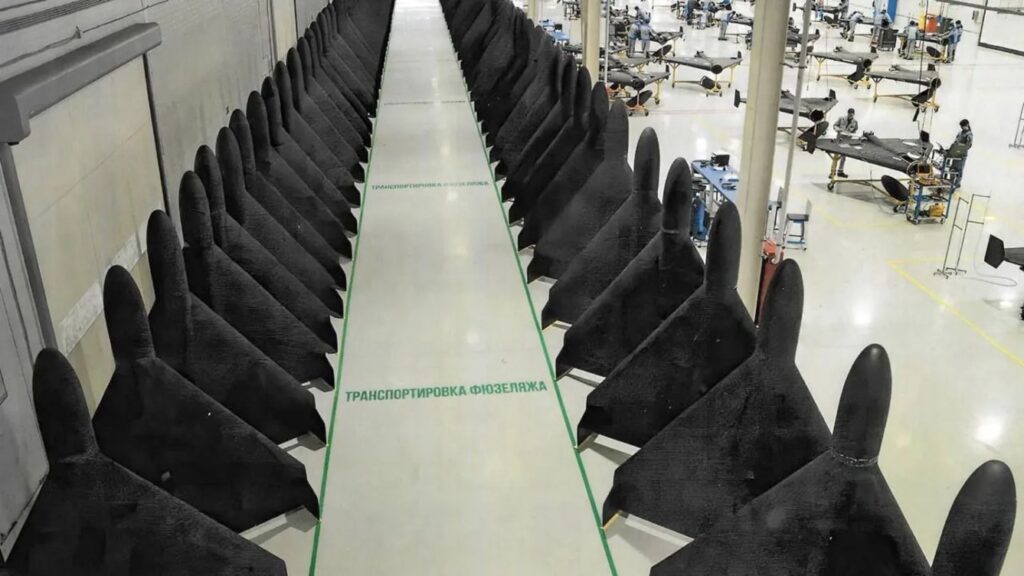

Russia increased long-range drone production from 15,000 in 2024 to over 30,000 this year, aiming for 2 million small tactical drones.

Iran adds another layer through its January strategic partnership with Russia, covering defense cooperation and intelligence sharing. The country is most known for providing Russian forces with Shahed-136 attack drones, which Russia has since been able to manufacture independently.

Compare this coordination to Western hesitation. While Russia receives troops, workers, and industrial components from allies, Ukraine’s Western partners debate long-range strike permissions for months and suspend aid deliveries.

Europe lacks “escalation dominance”—European powers cannot “dictate the levels of force and coercion” necessary to shape outcomes on their terms, Ledwidge believes.

Can Europe replace lost US missiles?

Think of Ukraine’s air defense like a castle’s defenses. Multiple walls protect against different threats.

The first wall: Shoulder-fired MANPADS that soldiers carry. Can Europe replace these? Yes. Poland’s Piorun and France’s Mistral systems work fine as substitutes.

The second wall: Short-range systems protecting tactical areas. Again, European alternatives exist, though in smaller quantities.

The critical third wall: Medium-range coverage that protects entire regions. Here’s where problems start. Ukraine relies heavily on American Patriots, NASAMS, and HAWK interceptors. Germany’s IRIS-T and the French-Italian SAMP-T offer similar capabilities, but “there aren’t as many launchers as there are Patriots,” Ledwidge explains.

The final wall: Long-range interceptors that stop ballistic missiles. This is where Europe falls short completely.

But Ukraine has already shown creativity under pressure. Necessity forced Ukrainian engineers to create hybrid “Franken-Buk” systems—mounting American AIM-7 missiles on old Soviet launchers when original Soviet missiles ran out.

Here’s the real problem: The dependency extends beyond ground systems to fighter aircraft. Ukraine’s F-16s use American AIM-9 and AIM-120 missiles. European nations possess limited stocks of compatible air-to-air munitions.

For HIMARS systems? “Europeans simply can’t backfill those—they’re an American form of munition,” Ledwidge notes.

Ukraine could potentially maintain basic air defense using European systems. But the country would lose much capability against Russia’s most dangerous weapons—ballistic missiles and long-range cruise missiles that require Patriot-level systems.

The timing couldn’t be worse. Russian engineers have systematically upgraded Shahed drones. Newer variants fly at 2,800 meters altitude and reach 550-600 km/h—too high for machine guns, too fast for helicopters.

Modern Shaheds carry 12-channel navigation systems that resist electronic jamming. Their 90-kilogram (198 lbs) warheads also double earlier destruction potential.

These technological advances create a perfect storm: just as Ukraine loses access to American interceptors, Russian weapons become harder to counter with existing European alternatives.

What’s next for Ukraine’s air defenses?

Ledwidge sees little optimism about European defense commitments. Recent promises of 150 billion euros for EU defense funds and 650 billion in loan facilities “will never be taken up because there isn’t sufficient commitment, particularly from Southern Europe.”

The €150 billion comes from the EU’s newly established Security Action for Europe (SAFE) regulation, approved in May 2025. It provides loans to member states for joint arms procurement and defense technology development. The €650 billion represents loosened fiscal rules allowing countries to increase national defense budgets substantially over the coming years under the ReArm Europe program.

Why does he believe these funds won’t materialize? Sophisticated weapons systems require enormous financial investments and years of development time. The gap between political declarations and actual capability generation reflects deeper structural problems in European decision-making.

His prediction extends beyond the current crisis: “There will be an even bigger panic when the Americans actually start withdrawing troops.”

For Ukraine, that panic has already begun. As Washington delays critical decisions and European rearmament remains mostly on paper, the country continues to fight under daily missile fire, often without the systems it urgently needs. Kyiv is still awaiting a response to its $30–50 billion weapons purchase proposal, a last-ditch effort to secure enough air defense and ammunition to survive the coming months.

While Europe debates fiscal frameworks and timelines, Ukraine is left asking a more immediate question: can its allies deliver real support now—before it’s too late?

(@MFA_Ukraine)

(@MFA_Ukraine)