A Strand of Hair Just Changed What We Know About the Inka Empire

Welcome back to the Abstract! Here are the studies that stood out to me this week, covering everything from silver to scat.

First, a story about an ancient Andean tradition that will somehow end with a full-sized replica of a person posthumously made with his own hair. Enjoy the ride!

Then: the health risks of climate change for children; you’ll never guess what came out of this otter’s butthole; and wow, Vikings sure were good at raiding, huh.

The tangled origins of Inka khipus

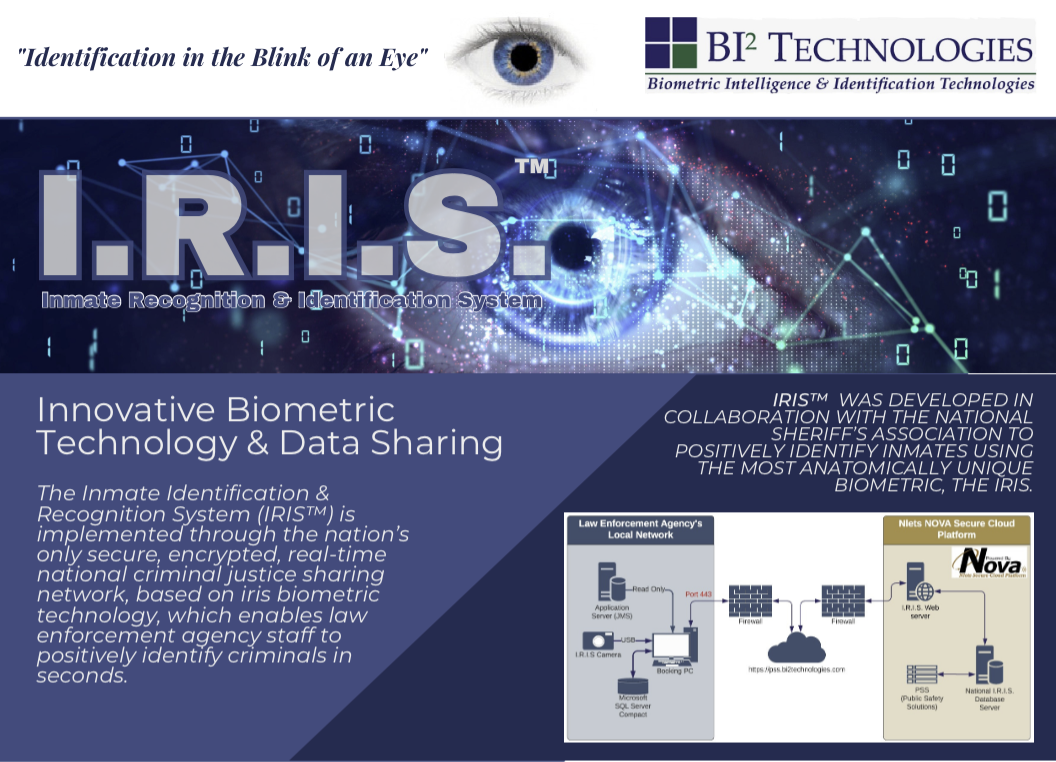

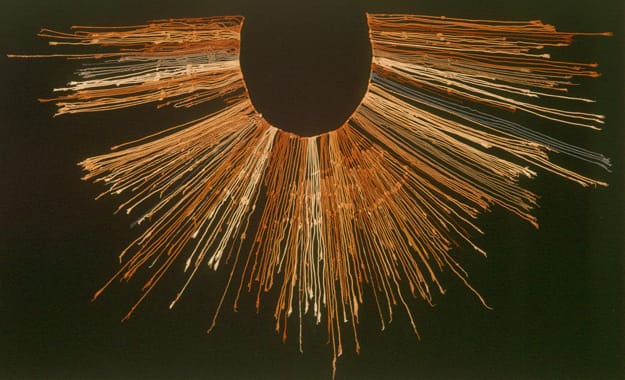

For thousands of years, Andean peoples have woven intricate patterns, known as khipus, that encode information into clusters of knots and multi-colored threads. Made from cotton, wool, and often human hair, khipus are an idiosyncratic form of writing used for a range of purposes like arithmetic, census-keeping, calendrical cycles, and more.

Spanish invaders, who overthrew the Inka empire in the 16th century, reported that only high-ranking bureaucratic men became khipu-makers (khipukamayuqs)—though this assertion has been challenged in the past by Indigenous sources.

Now, a strand of human hair woven into a 500-year-old khipu has resolved this centuries-old question. Scientists performed an isotopic analysis of the hair, revealing that the individual who wove it into the khipu was likely a low-status commoner with a simple plant-based diet. The discovery confirms that khipus were made by people from different classes and backgrounds, and that Inka women probably made them as well.

Khipukamayuqs “have been viewed primarily as imperial male elites who played key roles in running the empire,” said researchers led by Sabine Hyland of the University of St. Andrews. “However, the indigenous chronicler, Guaman Poma de Ayala”—who lived in the 16th century—”stated that women also made khipu records, explaining that females over fifty “[kept] track of everything on their [khipu],” the team added.

Hyland and her colleagues found a solution to the discordant accounts in a khipu called KH0631, which was made around the year 1498. Though the provenance of the khipu is not known, the primary cord was made of human hair, allowing them to unravel the diet of this ancient khipukamayuq from the elemental composition of their tresses.

The sampled strand was more than three feet long, and would have taken about eight years to grow. Carbon and nitrogen analysis of the hair indicated that it belonged to an individual that “ate a plant-based diet consisting primarily of tubers and greens with little consumption of meat or high-status plants such as maize,” according to the study. Strontium analysis showed “little marine contribution to the diet, indicating that the individual likely lived in the highlands.” Overall “this diet is a characteristic of low-status commoners, unlike the diet of high-status elites who consumed considerably more meat and maize,” the researchers said.

The team speculated that this long-haired khipukamayuq could have just been a proto-vegan, but that wouldn’t explain why there was so little maize in their diet given elites were professional beer drinkers.

“Obligatory drinking of maize beer formed a central feature of Inka ceremonies of governance in which high-ranking khipukamayuqs participated,” the researchers said. “Given the symbolic importance of hair in the Andes, and the frequent use of hair on the primary cord to indicate the khipukamayuq, our results indicate that the creator of KH0631 was likely a non-elite commoner” suggesting that “khipu literacy in the Inka Empire may have been more inclusive and widespread than hitherto thought.”

IIn addition to broadening our understanding of khipukamayuq origins, the study is full of amazing insights about veneration of hair in Inka culture.

“Hair in the ancient Andes was a ritually powerful substance that represented the individual from whom it came,” the researchers said. “Historically, when human hair was incorporated into a khipu’s primary cord, it served as a ‘signature’ to indicate the person who created the khipu.”

“For important ceremonies, the Inka emperor sacrificed his own hair,” they added. “His hair clippings were saved during his lifetime; after death, they were fashioned into a life-size simulacrum revered as the emperor himself.”

I strongly suggest we revive this funerary practice, so start saving your hair clippings for your wake.

In other news…

The kids are not going to be alright

The climate crisis is a tragedy for people of all ages, but kids are among the most exposed to harm. A new study provided an exhaustive review of climate-related threats to babies, children, and adolescents, which include: food insecurity, malnutrition, water scarcity, bad air quality, infectious diseases, exposure to extreme weather, displacement, trauma, and mental illness.

“Children are particularly affected by adverse environmental influences, as their immature organ systems are less able to cope with thermal stress and disease,” said researchers led by Paula Reichelt of the Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research. “Moreover, their developmental stage makes them especially vulnerable to long-term consequences; early-life nutrient or health disruptions can lead to permanent impairments in growth and development.”

“Due to the relatively modest global efforts by political decision-makers to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, further global warming and the associated negative developments in child and adolescent health are likely,” the team concluded.

“Relatively modest” is doing a lot of work in that sentence. While I recognize the allure of doomerism or tuning out from these horrible realities, I recommend carrying around a manageable dose of incandescent rage at all times over the world we’re leaving behind to kids who had nothing to do with this mess.

Parasite lost (in otter poop)

You have to love a study that was inspired by an otter crapping out a weird red worm on a dock in the Chesapeake Bay. Curious about the poopy parasite, researchers sought out other otter “latrines” and discovered that these furry floaters eat a lot of parasites, probably because infected prey is often easier to catch. In this way, otters efficiently remove parasites from ecosystems; it may be a bummer for any infected prey on the otter menu, but is beneficial to the wider population.

“This study is the first to characterize river otter latrines and diet in a tidally influenced estuarine habitat within the Chesapeake Bay,” said researchers led by Calli Wise of Smithsonian Environmental Research Center.

“Our results indicate that river otters consume a wide range of terrestrial and aquatic fauna, primarily consisting of finfish and crustaceans, but also including frogs and ducks,” the team said. “Multiple parasite species were identified, including parasites of river otters and those infecting prey, indicating that parasites likely play an important role in both prey availability and otter health.”

Tl;dr: Otters are parasite vacuums. Yet another reason to love these cuddly creatures and forgive their more unsavory attributes.

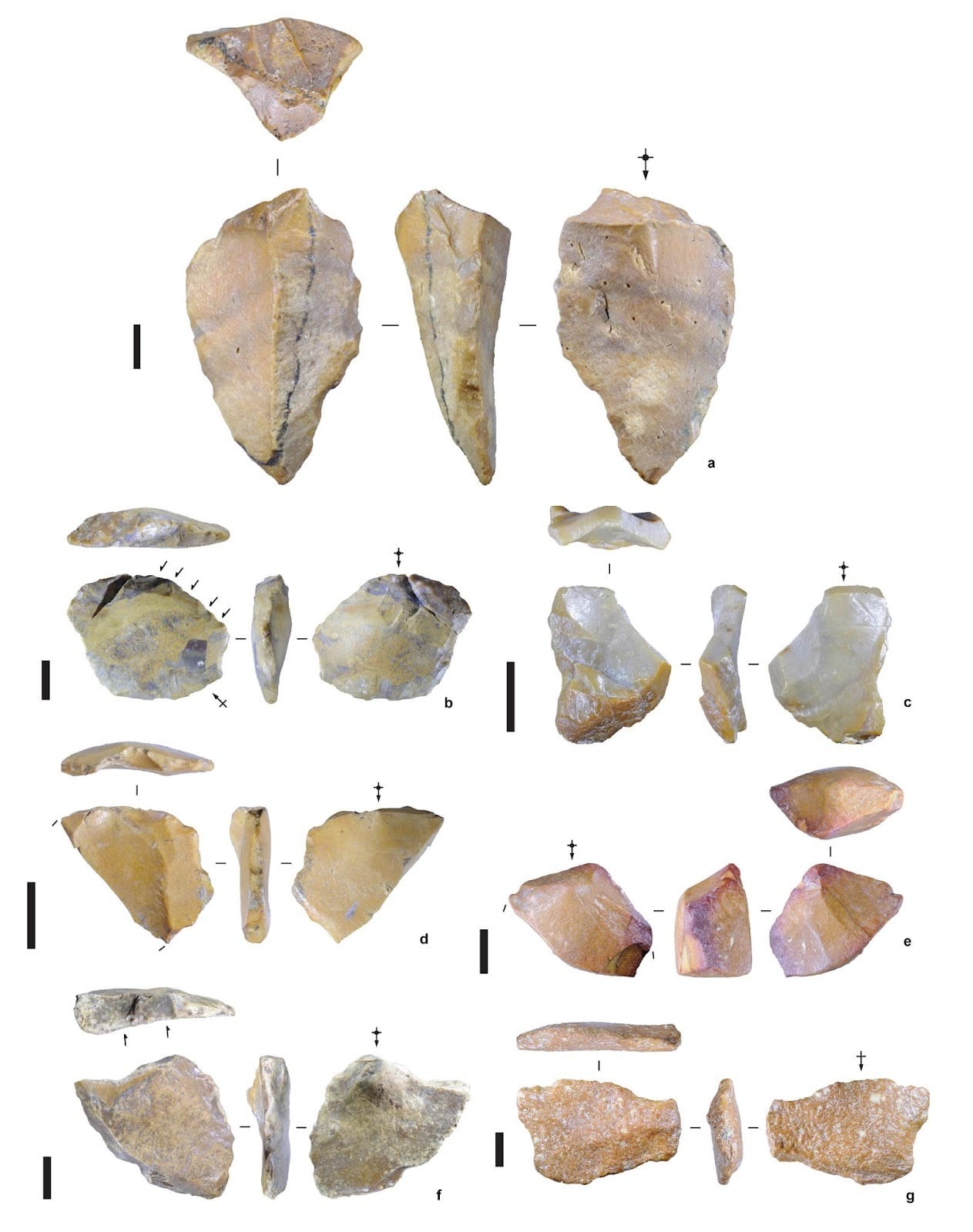

Some Viking booty, as a treat

We’ll end, as all things ideally should, with treasure. A new study tracks down the likely origins of a hoard of gold and silver items—including a sword pommel, jewelry, and several ingots—that were stashed by Vikings in the English town of Bedale, North Yorkshire, more than 1,200 years ago.

Vikings are well-known for their epic raids (source: Assassin’s Creed: Valhalla) and this particular hoard included far-flung loot sourced from across Europe and the Middle East.

“The results indicate a dominant contribution of western European silver, pointing to the fate of loot seized by the Vikings during their raids on the Continent in the ninth century,” said researchers led by Jane Kershaw of the University of Oxford. “Nonetheless, Islamic silver is also present in several large ingots: silver from the east—the product of long-distance trade networks connecting Scandinavia with the Islamic Caliphate—permeated Viking wealth sources even in the western part of the Viking overseas settlement and should be seen as a significant driver of the Viking phenomenon.”

“The Vikings were not only extracting wealth locally; they were also bringing it into England via long-distance trade networks,” the team concluded.

With that Viking spirit in mind—skål, and see you next week.