Ukrainian soldier first fought against Russia and then against Ukraine – his story reveals forced conscription in occupation

Ukrainian soldier Pavlo Pshenychnyi fought Russian-backed forces in Donetsk Oblast in 2019. Six years later, he found himself fighting for Russia against his own countrymen, while Russia launched an explicit full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

How does a Ukrainian war veteran end up in enemy uniform? The answer reveals Russia’s systematic transformation of occupied territories into military recruitment grounds, where residents face a brutal choice: prison or the front lines. And often prison is not something that’s deserved but rather inflicted through fabricated charges and threats.

Pshenychnyi’s account, given in an interview with Ukrainian news agency Hromadske after his capture by Ukraine’s Freedom battalion, exposes the machinery behind Russia’s forced conscription in occupied areas.

His story traces a path from Ukrainian defender to unwilling Russian soldier—a journey thousands may be forced to take if Russia continues to grab new territories.

Before the full-scale invasion: he fights against the Russians

Why did Pshenychnyi join Ukraine’s military in 2018? Simple economics.

“There was no work,” he told Hromadske. His uncle knew someone at the military commissariat who mentioned openings for drivers with commercial licenses.

“Work is work—what’s the difference where you work?” Pshenychnyi reasoned.

His original enlistment in the Ukrainian army had nothing to do with patriotism or defending his homeland. It was purely economic necessity.

Pshenychnyi signed his contract in October 2018. By November, he was manning positions near Avdiivka, where he could see both Donetsk airports from his post. The war felt manageable then. Until 24 February 2019.

That day, Ukrainian snipers from nearby Pisky killed two Russian soldiers, exposing Ukrainian positions. A week later came the response. A Russian sniper’s bullet found Pshenychnyi’s back, killing his fellow soldier Serhiy Luzenko instantly.

Pshenychnyi survived, crawled to safety, and eventually made it home to southern Kherson Oblast with a disability certificate and two military medals.

He thought his war was over.

Ukrainian veteran monitored by Russian occupiers

When Russian forces occupied Kalanchak, Kherson Oblast, in February 2022, neighbors quickly identified the local veteran.

“These are good neighbors,” Pshenychnyi said with bitter irony. “Although they’re not very good.”

The first occupiers weren’t even Russian but mostly Dagestanis and other nationalities who barely spoke Russian. They knew enough to search his apartment and confiscate his veteran documents, disability certificate, and medals.

What followed was routine intimidation. New occupying units rotated through monthly, each making their presence known.

“They’d come in on their wave, might hit or not hit, walk around the house, stomp around, look around,” Pshenychnyi recalled. “I was constantly in their field of view.”

During one visit, with his newborn daughter sleeping nearby, Russian soldiers fired two shots into his ceiling. Their message was clear: “You killed our people there.”

Pshenychnyi learned quickly that arguing was pointless and potentially fatal.

“You can’t prove anything to them,” he explained. “There was no point in even saying anything, you could make it worse for yourself.” This was the reality of occupation—silence became survival.

Failed attempts to run away with wife and infant

Could Pshenychnyi’s family escape? They tried twice.

The first attempt came eight months after his daughter’s birth in June 2022. At the Russian border, guards turned them back. The child had only a medical document from the hospital—no official birth certificate that Russian authorities would accept.

Six months later, Russian police and child services began visiting. They questioned why the child lacked Russian documents and who the parents were to her.

“They even wanted to take the child—just take her and take her somewhere,” Pshenychnyi said.

Terrified of losing their daughter, his wife obtained Russian birth papers for the child. They tried leaving again, this time through Lithuania. But Lithuanian border guards saw the mismatch: Ukrainian passports for the parents, Russian birth certificate for the child. Again, turned back.

They were stuck.

Fabricated drug charges become pathway from prison to front lines

In September 2024, police arrived claiming someone had stolen tools and appliances in the village. They’d heard a truck had delivered items to Pshenychnyi’s house the day before. Could they search?

While Pshenychnyi opened his first basement room for inspection, officers positioned themselves near the second room. “While I was opening the second one, they were already shouting: ‘Oh, found everything. No need to search anymore!'”

What did they find? “They pulled out a huge bag of grass, marijuana, brought it into the house,” Pshenychnyi recalled.

Two witnesses emerged from the police car right on cue.

He believes they planted evidence to simply force him into Russian service.

The trial stretched from late 2024 to 29 May 2025. Pshenychnyi faced 12.5 years in prison. But as the judge finished reading the sentence, military commissariat officials entered the courtroom.

“That’s it, here’s your prison. You’re going to the army,” they announced.

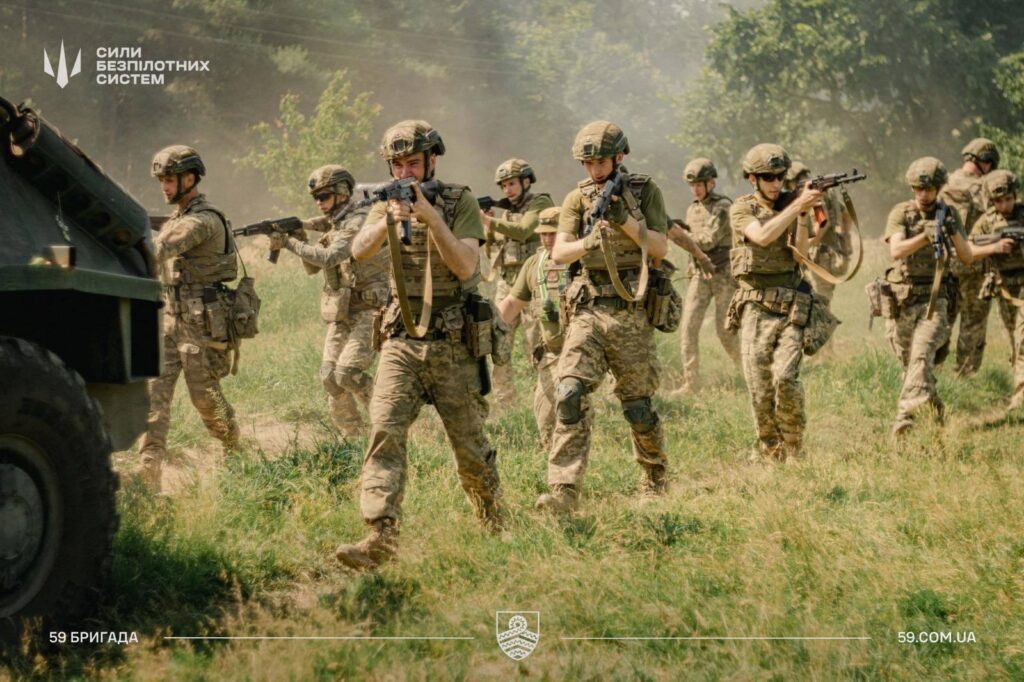

Former prisoners train new Russian recruits in deliberately brutal conditions

What’s Russian military training like for forced conscripts? Deliberately brutal.

At the Makiivka training facility, former prisoners, who were pardoned in exchange for surviving combat, served as instructors. These “Storm Z” veterans had already proven themselves expendable and lived to tell about it.

Training focused on basic assault tactics: how to storm buildings, shoot between ruins, apply tourniquets, spot tripwires. But the real lesson was endurance. Twenty-kilometer daily marches in extreme heat, minimal water rations, constant physical stress.

“They don’t give water during walking so you don’t die without water,” Pshenychnyi explained. The logic was twisted but clear: condition soldiers for the deprivation they’d face at the front.

Who else trained alongside him? A mix that revealed Russia’s recruitment desperation. Some volunteers who’d fought in 2014’s separatist militias. Alcoholics who’d signed contracts while intoxicated and didn’t remember agreeing. Residents from other occupied territories facing similar forced choices.

Many were HIV-positive former prisoners serving 20-plus year sentences, identifiable by red armbands on their left arms. Several died during training from heart attacks because their bodies accustomed to Siberian cold couldn’t handle the sudden heat and physical demands.

The most desperate cases served as human mine detectors. Russia would strip reluctant soldiers of body armor and weapons, point to a target, and promise equipment back if they survived the approach.

Among the most shocking elements were the foreign fighters—Somalis and others who displayed an almost inhuman indifference to casualties. Pshenychnyi witnessed this firsthand when a group of 10 Somali fighters walked ahead of his unit.

“Such people that I don’t know what could be told to them that they go like that,” Pshenychnyi said, struggling to explain their behavior.

When a mortar shell killed one of the Somalis directly in front of the group, the others simply stepped around the body and continued their advance without pause or emotion.

“That’s it, he’s dead. They bypassed him, they went further. And generally they don’t care,” he said. “They go specifically there to do the task. That’s it.”

Russian commanders leave wounded soldiers to rot in trenches

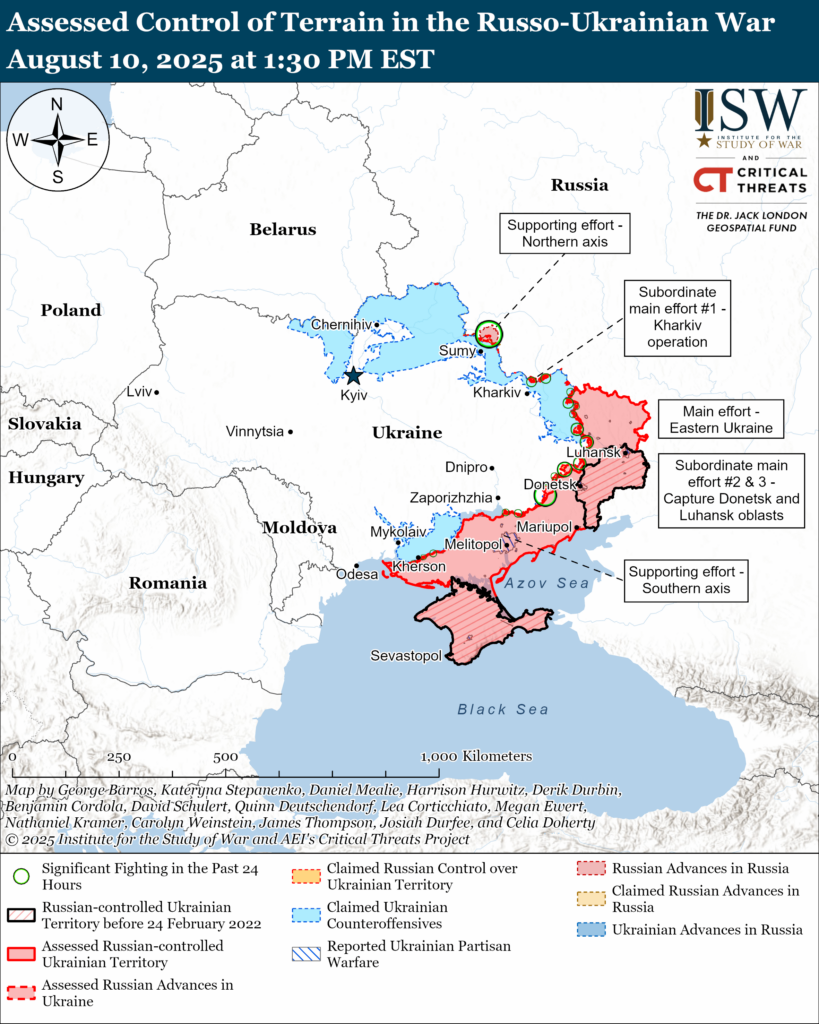

After six weeks of training, Pshenychnyi received deployment orders. Officials confiscated phones, bank cards, anything connecting soldiers to their previous lives. Then came the trip to Avdiivka in Donetsk Oblast.

The supply situation was immediately clear.

“They gave very little water – for three people per day maximum one and a half liters, and not always full,” Pshenychnyi said.

Soldiers near villages or rivers could sometimes find additional sources. Those in remote forest positions simply went without.

What were their orders? Hold positions 250 meters apart across forest strips. Shoot anyone approaching unless radio communications specifically cleared their movement.

Russian commanders showed little concern for soldier welfare. Pshenychnyi described radio communications where a territorial defense commander threatened troops under mortar fire:

“I’ll shoot you myself, I’ll get you out of the tank now and shoot you… if you don’t continue movement.”

Wounded soldiers received no evacuation.

“If you’re wounded, you have only one way. Either not to be wounded, or better immediately dead. Because you’ll rot in landings and you won’t have evacuation,” Pshenychnyi explained.

Freedom battalion fighters shocked to capture fellow Ukrainian veteran fighting for Russia

When Ukrainian Freedom battalion fighters approached their forest position near Avdiivka, Pshenychnyi and his partner were following standard orders: shoot anyone who approached their sector unless radio communications specifically cleared them.

His partner immediately grabbed his rifle and aimed at the approaching figures. But Pshenychnyi quickly assessed their situation—they were surrounded and outgunned.

“Put down the rifle, why will all this shooting start now?” he told his companion, recognizing the futility of resistance. “What can I do if they’re already standing with rifles? I won’t even have time to take it, whether they’re ours or not, whoever they are.”

Initially, Pshenychnyi couldn’t tell who was approaching their trench. “Well, maybe ours, maybe they’re coming from somewhere. Russians, I think, what’s the difference?” he recalled thinking.

The soldiers called out something, but he couldn’t immediately recognize their identification marks. Only when he got a clear view of their uniforms did recognition dawn.

“Then I look, pixel camouflage, I say: ‘Oh, Ukraine, give us water!'” he called out.

The Ukrainian soldiers were shocked to discover they’d captured a fellow veteran. One asked directly:

“What do you think your guys you fought with since 2014 would say if they found out you’re here now?”

The way Ukrainian soldiers treated Pshenychnyi as a prisoner of war (POW) surprised him.

“I imagined that I would sit there tied up somewhere, and here it’s completely different. And they give food… And they brew coffee,” he shared. “I was glad that I surrendered—otherwise in a few days I would have simply died of dehydration.”

More people in occupation face forced conscription if Russia is not stopped

How many others face Pshenychnyi’s dilemma? His account suggests thousands.

The recruitment system extends beyond fabricated criminal cases. All men under 30 in occupied territories face conscription for military service in Russia. Some serve domestically, others get sent to combat zones.

Those who initially refuse face calculated deception. They’re allowed to live normally at base for weeks, even permitted shopping trips. Just when they think they’ve escaped combat duty, orders arrive: join the assault units or face consequences.

When asked about the common saying among Ukrainians that “if you don’t serve in your own army, you’ll serve in someone else’s,” Pshenychnyi’s response was stark:

“That’s how it will be. If they capture territories, then there will be no choice for anyone, like here.”

Can residents of occupied territories avoid this fate? Pshenychnyi’s assessment left little hope: “There will be no choice at all.”

Russia isn’t just occupying Ukrainian territory. It’s systematically converting Ukrainian citizens into weapons against their own country, using fabricated criminal cases, manipulations and threats to families.

Read also

-

144 Russian prison guards exposed for torturing Ukrainian POWs—investigation reveals daily routine of cruelty and family life

-

Russian “Doctor Evil” posts about loving family and medical pride online, while he degrades and tortures Ukrainian POWs in reality

-

Ukraine captures Russian soldier who tortured and executed Ukrainian POWs. Now he faces life in prison

-

Russians target orphans and disabled families’ children for military draft in Kherson Oblast

Oleh Shupliaк

Oleh Shupliaк

Starokostiantyniv, Khmelnytskyi Oblast was the main target. According to the Regional Military Administration, most missiles and drones were shot down, but…

Starokostiantyniv, Khmelnytskyi Oblast was the main target. According to the Regional Military Administration, most missiles and drones were shot down, but…