“Increasingly difficult”: Kallas says EU can’t yet agree how to use frozen Russian assets for Ukraine (INFOGRAPHIC)

On Friday, the EU made Russian asset freezes permanent—removing the risk that Hungary could veto renewals and force the money back to Moscow. By Monday, the bloc’s top diplomat was admitting the next step is “increasingly difficult.”

EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas told reporters in Brussels that converting frozen Russian assets into loans for Ukraine remains the “most credible” funding option—but member states still can’t agree on how. “The other options are not really flying,” she said.

“We are not there yet, and this is increasingly difficult, but we still have some days.”

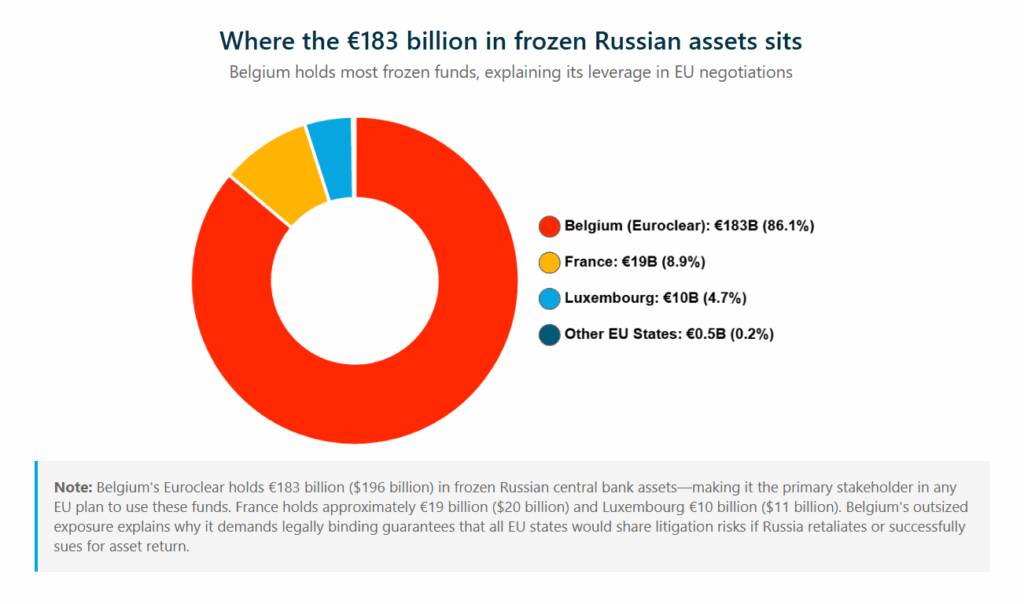

Those days are running out. EU leaders will meet on Thursday and Friday to decide whether €210 billion in immobilized Russian sovereign assets can be used to back a loan that would fund Ukraine’s military and civilian needs through 2027. Without an agreement, Europe loses its strongest card in any peace negotiations with Moscow.

Belgium holds the key

Belgium, where most assets sit at the clearinghouse Euroclear, backed the indefinite freeze last week. But Prime Minister Bart De Wever’s government simultaneously called on the Commission to propose alternative funding options—a demand now joined by Malta, Bulgaria, and Italy.

The problem: no alternatives exist.

The previous backup—a €90 billion eurobond scheme—died when Hungary vetoed it on 5 December. Direct funding from national budgets faces even steeper resistance.

Russia is applying pressure of its own. The Bank of Russia filed a lawsuit in Moscow on Monday seeking 18.2 trillion rubles ($229 billion) from Euroclear—the latest in a series of legal actions since 2022 that feed Belgian concerns about liability.

Berlin talks raise the stakes

The asset deadlock comes as US-Ukraine peace negotiations resume in Berlin this week with European participation. US envoy Steve Witkoff and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy are both expected.

The Kremlin has already rejected European modifications to Trump’s peace plan as “unacceptable”—and Moscow has accused Chancellor Friedrich Merz of “warmongering” for pushing the frozen assets scheme.

The timing creates a bind.

If Europe can’t agree on using Russian money to fund Ukraine, its influence in shaping any peace deal shrinks. Putin isn’t negotiating seriously because he’s betting Europe will exhaust itself first. A two-year funding package backed by frozen assets would break that bet.

EU leaders have 72 hours to prove him wrong.