Whatever you do, don’t march 12 miles with two landmines strapped to your back while Ukrainian drones patrol overhead

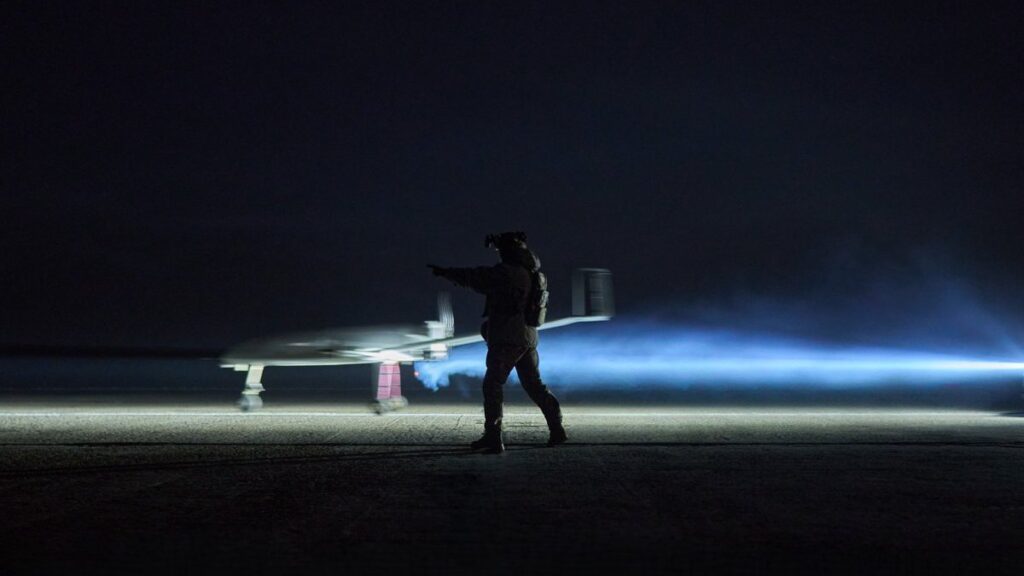

A dramatic video, captured by the Ukrainian 225th Assault Regiment’s Black Swans drone unit and translated by Estonian analyst WarTranslated, depicts an increasingly common phenomenon: Russian soldiers exploding after a nearby drone strike cooks off the ammunition the soldiers are carrying.

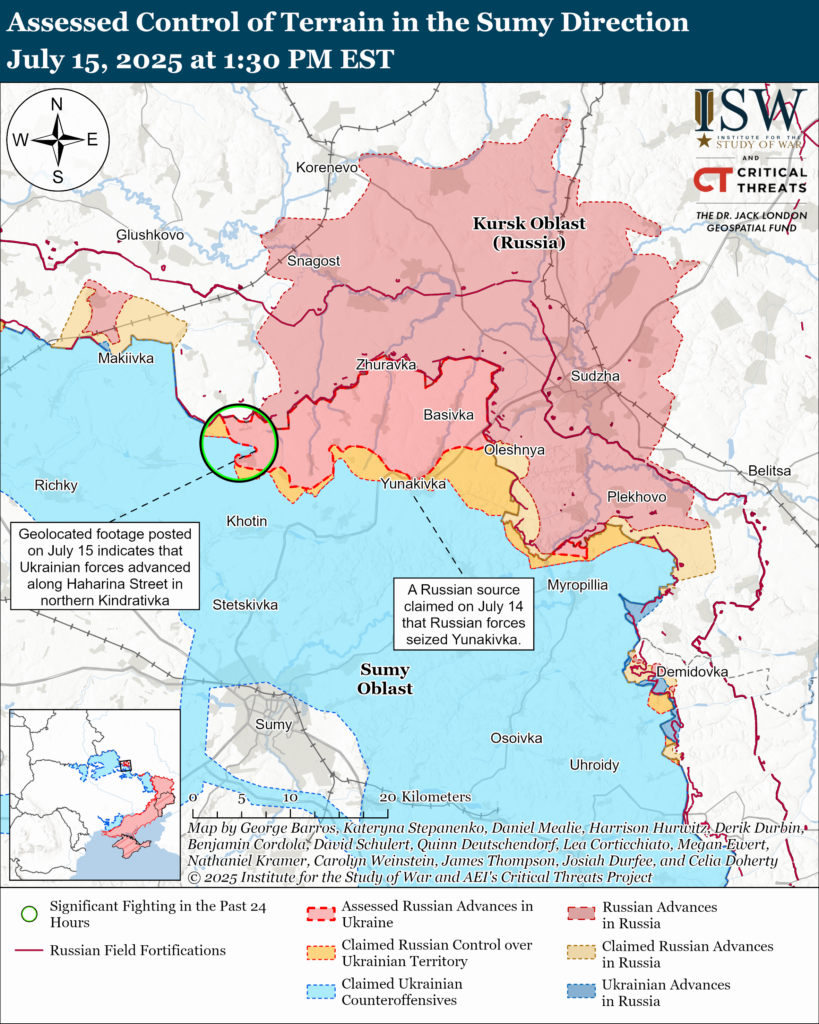

The blast apparently took place somewhere in Sumy Oblast in northeastern Ukraine, where Ukrainian brigades have been slowly pushing back an incursion by Russian infantry.

Infantry self-immolation is one of the second-order effects of the accelerating “de-mechanization” of the Russian armed forces as Russia’s wider war on Ukraine grinds into its 42nd month. The Russians have written off more than 20,000 combat vehicles and other heavy equipment—far more than they can immediately replace through new production and the reactivation of increasingly scarce stored vehicles.

With only a few exceptions, Russian troops now march into battle in Ukraine—or ride on motorcycles. Even cargo trucks are in short supply, meaning the troops themselves are the supply line. But in carrying bullets, grenades and mines on their persons, they risk self-destruction from drone near-misses.

American analyst Andrew Perpetua noted Russia’s human supply lines while scrutinizing the battlefield just south of the eastern city of Pokrovsk earlier this year.

Perpetua recently identified, in one shocking video, around 150 destroyed Russian trucks on a two-mile stretch of one of the several roads threading west from the Russian stronghold of Selydove toward the village of Shevchenko, a few miles south of Pokrovsk. That’s a wrecked Russian truck every 70 feet.

Russian infantry are now carrying grenades and ammunition on themselves, increasing the risk of secondary explosions. A nearby hit is often enough to set off their own munitions. Footage shows the Black Swan unit in action. pic.twitter.com/vqc5MqSYZo

— WarTranslated (@wartranslated) August 2, 2025

Roads of death

That “road of death,” which the Russians persist in using—with predictably bloody results—was patrolled by the drone team supporting one particularly aggressive Ukrainian battalion that held the line around Shevchenko and, in December, waged a successful campaign against a Russian force 20 times its size. The Ukrainian campaign halted the grinding, yearlong Russian advance on Pokrovsk—although temporarily.

The Ukrainians “moved these drone units down to this area and that’s when they started setting up their kind of drone superiority, where they took complete control of the sky,” Perpetua recalled.

“The Russians basically couldn’t fly drones,” he added. “Their drone would take off, Ukraine would shoot it down and then attack the drone pilots—and they couldn’t fly drones. The Russians were complaining of, like, a 10-to-one or worse drone ratio.”

“That drone advantage is what eventually led to this stopping the Russian attack through shutting down all of these roads,” Perpetua said. The Ukrainian drone pilots “had this policy, where they wanted to first take out the Russian drones and then—once those drones were taken out—go for the supply routes.”

Heavy hexacopter “vampire” drones fitted with night-vision gear and carrying loads of grenades or mines, many of them flown by the famed Ukrainian Birds of Magyar drone group, inflicted the most damage on the roads to Shevchenko.

The Russians are adept at downing the 50-pound vampires with two-pound first-person-view drones that blow up on contact. But having suppressed the Russian drone teams around Shevchenko, the Ukrainian drone teams could fly their vampires with impunity.

Smaller FPV drones joined the vampires, including some fiber-optic models. After blasting every Russian supply truck in sight, the drones ranged farther south and east—and located the depots where the Russian regiments were storing the trucks and other vehicles that remained.

“They went to every vehicle depot and just blew them all up so they had, like, no tanks, no BMPs,” Perpetua mused. “They took out all their MRAP [armored trucks] and then they just shut down every single road, so they starved out the Russians.”

To reinforce Shevchenko, the Russians had to walk … for kilometers. “Their engineers were saying, ‘We have to build a minefield, but we can’t bring any trucks up. So everyone has to carry two mines,’” Perpetua laughed. “So there’s these videos of infantry marching up and, you know, they’re being told that you have to march 20 kilometers. You have to bring all of the food and ammo to last two weeks and you have to carry two landmines.”

The practice is now widespread in the de-mechanized Russian military. Already harried by Ukrainian drones, artillery and mines, Russian infantry now have another problem: their own explosive baggage.

(@iEndure_4evr)

(@iEndure_4evr)