Independence Day of Ukraine: celebrating independence when fighting for freedom

Today, Ukraine marks its 34th Independence Day. But this isn’t 1991’s euphoric declaration of sovereignty, or even 2021’s military parades down Kyiv’s main boulevard. This is 24 August 2025 – Independence Day during the fourth year of Russia’s attempt to entirely erase Ukrainian statehood.

The holiday that once celebrated freedom now embodies the fight to keep it.

When independence became survival

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion on 24 February 2022, Ukrainian Independence Day has transformed from a ceremonial occasion into something far more urgent: proof that the country Putin said “doesn’t exist” refuses to disappear. In August 2022, Ukrainian media reported how Independence Day celebrations replaced traditional military parades with displays of destroyed Russian equipment, turning Kyiv’s Khreshchatyk street into a graveyard of Russia’s failed conquest.

The numbers tell the story of this transformation. Before 2022, just 37% of Ukrainians considered Independence Day personally important. By 2024, that figure had jumped to 64% – war crystallizing what freedom actually means when you risk losing it.

From USSR exit to democratic frontline

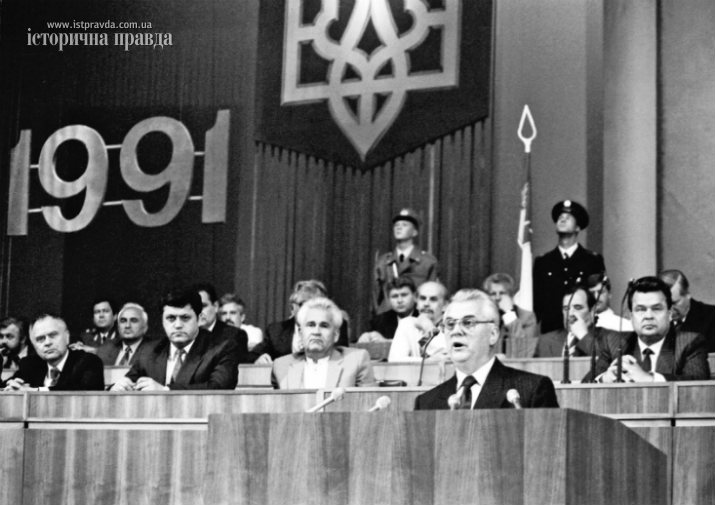

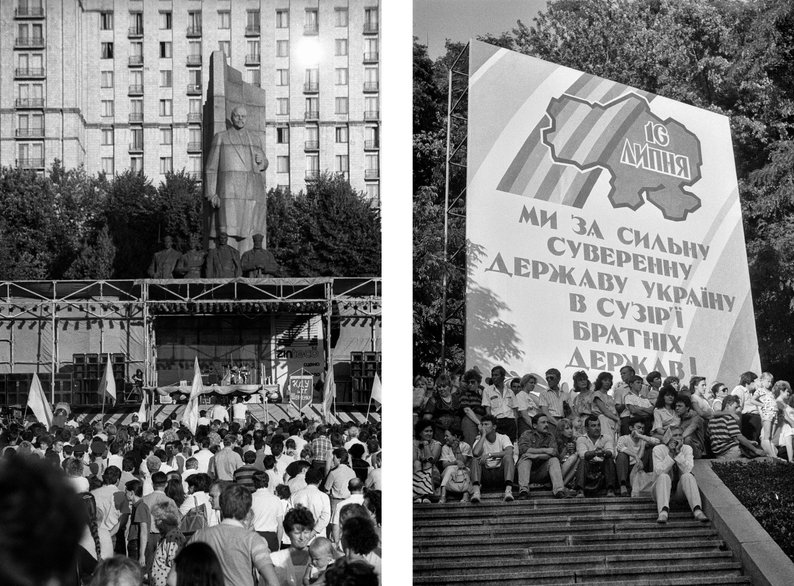

Ukraine’s independence story began modestly enough. On 16 July 1990, the Verkhovna Rada declared sovereignty within the Soviet Union by a vote of 355 to 4. It seemed like careful political maneuvering, not revolution.

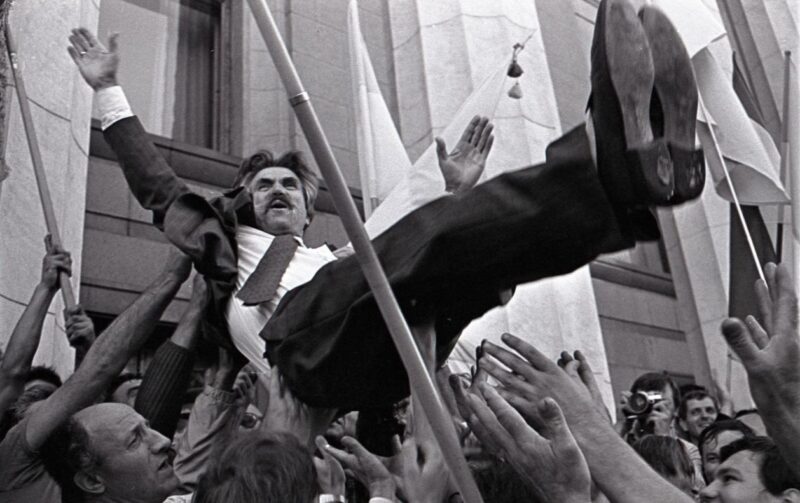

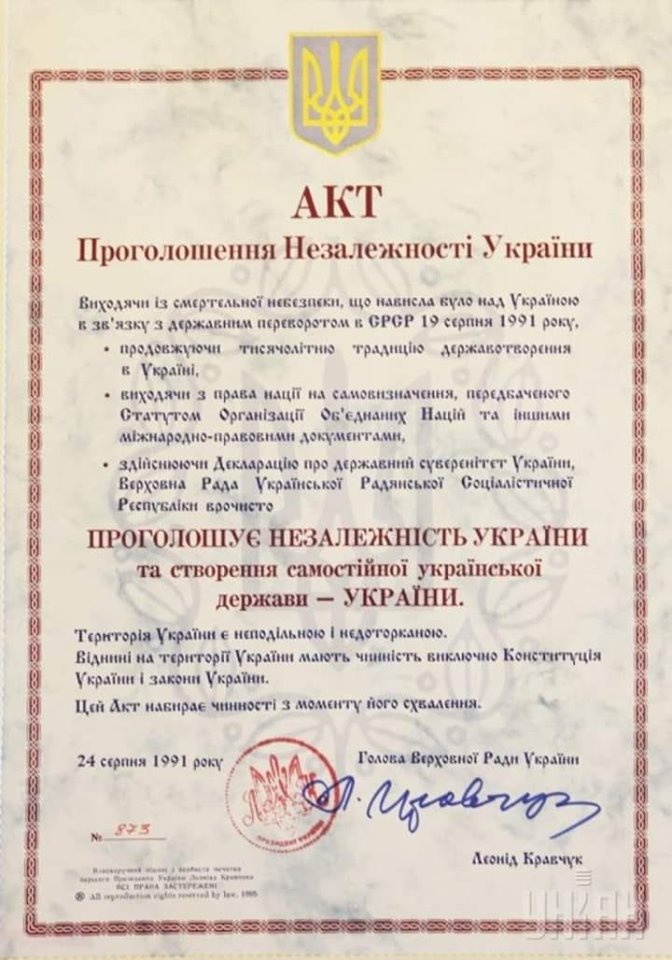

But the failed Moscow coup of 19 August 1991 changed everything. Five days later, on 24 August, Ukraine’s parliament adopted the Act of Declaration of Independence, formally breaking with the USSR. The 1 December 1991 referendum wasn’t even close: over 92% of voters confirmed independence, with 84% turnout across the country.

What started as bureaucratic independence became something much larger when Ukraine chose Europe over Russia’s sphere of influence.

The real test for independence came in 2013

Independence Day celebrations remained largely ceremonial with military parades until the Revolution of Dignity transformed Ukraine’s trajectory. When hundreds of thousands gathered on Kyiv’s Independence Square in late 2013, they weren’t just protesting President Viktor Yanukovych’s decision to abandon EU integration – they were defending the right to choose their own future.

The revolution that killed nearly 100 protesters in February 2014 established a crucial principle: Ukrainian independence meant more than just having your own flag.

It meant the freedom to align with democratic values against authoritarian pressure.

Russia’s immediate response – seizing Crimea and launching war in Donbas – proved the point. Moscow couldn’t tolerate a neighboring democracy that offered an alternative to Putin’s totalitarian model.

Independence under fire

The full-scale invasion that began 24 February 2022 turned Independence Day into something unprecedented: a wartime celebration of national survival. Instead of showcasing Ukrainian military power, the holiday now demonstrates Ukrainian resilience.

Recent Independence Day observances have featured:

- Displays of captured Russian equipment instead of military parades

- International solidarity events in dozens of countries

- Cultural programs highlighting Ukrainian identity under attack

- Memorial services for defenders killed protecting sovereignty

President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has repeatedly framed the ongoing war as Ukraine’s second war of independence – the first won through voting, the second requiring fighting.

Why this matters beyond Ukraine

Ukraine’s evolving Independence Day reflects a broader global struggle between democratic self-determination and authoritarian imperial ambitions. What happens to Ukrainian sovereignty affects the international system that emerged after World War II.

Independence Day in Ukraine now serves multiple strategic purposes:

- Diplomatic tool: Rallying international support around the principle of territorial integrity

- Domestic unity: Strengthening national cohesion during an existential crisis

- Information warfare: Countering Russian narratives about Ukrainian “artificial” statehood

- Democratic symbol: Inspiring other nations facing authoritarian pressure

The independence celebration that became resistance

On this 24 August 2025, Ukrainian Independence Day carries weight it never held during peacetime. Each year that the country survives Putin’s war of extermination, the holiday grows in significance – not just for Ukraine, but for anyone who believes smaller nations have the right to exist independent of their larger neighbors’ imperial ambitions.

The question isn’t whether Ukraine celebrates its 34th Independence Day. The question is what that celebration will mean for the future of national sovereignty in an era when major powers increasingly view international borders as random lines rather than laws.

Ukraine’s fight for independence continues.