Vue normale

-

#MonCarnet

-

Jeux vidéo et formation chez AWS

Mon Carnet, le podcast · {ENTREVUE} – Carl-Edwin Michel rencontre Sébastien Stormacq de AWS Carl-Edwin Michel s’entretient avec Sébastien Stormacq, développeur principal chez AWS, alors que AWS utilise désormais des jeux vidéo, accessibles via la plateforme gratuite Skill Builder, pour former le public à ses services infonuagiques et à l’IA. Plusieurs établissements d’enseignement supérieur au […]

-

Euromaidan Press

-

The West is losing the information war because it won’t fight dirty

You show Russians footage of their soldiers dying in Ukraine. They get angry—and mobilize to avenge them. You appeal to their humanity with pictures of Ukrainian children killed by Russian bombs. They shrug. You try facts about war crimes. Nothing. Peter Pomerantsev’s latest book, “How to win an information war,” distills lessons of WW2-era British-German propagandist Sefton Delmar for the current Russo-Ukrainian war But tell them criminals are being released from prison to join the army?

The West is losing the information war because it won’t fight dirty

You show Russians footage of their soldiers dying in Ukraine. They get angry—and mobilize to avenge them. You appeal to their humanity with pictures of Ukrainian children killed by Russian bombs. They shrug. You try facts about war crimes. Nothing.

But tell them criminals are being released from prison to join the army? That their sons might get raped by fellow soldiers? That crime is soaring back home while they’re dying in Ukraine?

Now you’ve got their attention.

This counterintuitive discovery comes from Ukrainian psychological operations teams who’ve spent three years learning what British propagandist Sefton Delmer figured out fighting the Nazis: facts don’t defeat propaganda. Self-interest does.

“People see the corpses of dead Russians and they’re like, well, I’m going to go and defend them,” Peter Pomerantsev tells me, describing Ukrainian research into failed propaganda attempts.

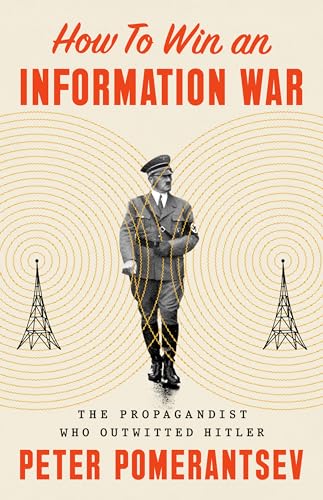

The author of “How to Win an Information War” has spent years studying both Soviet disinformation and Western attempts to counter it. His latest book, just translated into Ukrainian, resurrects Sefton Delmer, a forgotten genius who ran Britain’s “black propaganda” operations against Nazi Germany.

What Delmer understood—and what Ukraine is rediscovering—is that authoritarian propaganda doesn’t work through logic. It works through permission.

The inner pig dog strategy

Delmer called it appealing to the “inner pig dog”—that part of human nature that’s selfish, greedy, and looking for an excuse to save its own skin.

While the BBC broadcast noble appeals to German democracy, Delmer’s radio stations told Germans it was fine to be corrupt because their officers were stealing everything anyway. Why die for these scum?

“He’d never say that, though,” Pomerantsev explains.

Delmer’s programs featured soldiers raging about corruption, giving lurid details about what Nazi officials were eating while troops starved.

The message was indirect but clear: everyone’s looking out for themselves. You should, too.

One of Delmer’s most successful creations was “Der Chef,” a fake German radio station that posed as an underground voice of disgusted German soldiers. Der Chef would rail against SS corruption with stories so scandalous they became irresistible. When the Nazis converted the monastery of Münsterschwarzach into a military hospital, Der Chef spun a lurid fantasy:

“Two hundred SS men marched into the monastery… A bawdy house was made out of the monastery for the SS men and their whores. The holy mass gowns are used as sheets, and the women wear precious lace tunics made out of choir robes with nothing underneath them… Like this, they go into the chapel and drink liquor out of the holy vessels…”

Der Chef was outraged at such blasphemy—but always returned to these topics, the way tabloids show disgust at depravity while giving readers an excuse to enjoy it.

The approach worked perfectly: breaking taboos against insulting the SS while deepening rifts between party and army, party and people.

But Delmer’s genius wasn’t just in the sensational content.

His operations provided genuinely useful information to Germans—warnings about which districts would be bombed, updates on cities that had been struck, so soldiers could take guaranteed leave to help their families.

The stations posed as German broadcasts, so listeners wouldn’t get in trouble if overhead. They treated Germans as human beings, even while subverting them.

“His radio shows were full of pornography, aggression, a lot of color. It was definitely more than the BBC. It was very tabloid and really rather remarkable,” Pomerantsev explains.

But Delmer’s method was always indirect: “He tells stories about people deserting and we’ll always be like, how horrendous, these traitors are deserting, and give details how they desert with the intention of making people want to desert.”

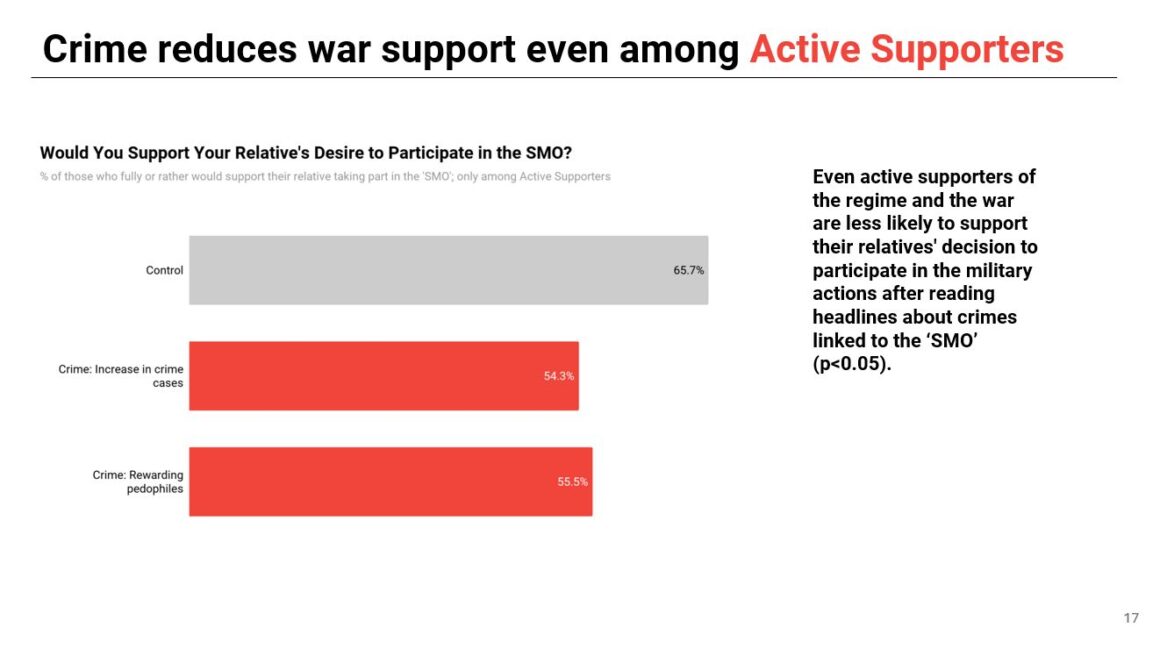

The parallels to Russia today are striking. Ukrainian research has found similar patterns:

“Several research groups have found the same thing—that the most effective messaging is around the rise of crime rates in Russia to undermine the desire of people to send their families to the war,” Pomerantsev notes.

The crime messaging works because it targets what Putin supporters actually value:

- Order and stability – Rising crime rates suggest Putin’s “strong hand” is failing

- Personal safety – Stories about criminals in the army threaten families directly

- Elite competence – Military chaos reflects broader governmental failure

“People who support the war the most are very authoritarian. They want Putin’s strong hand. They want order,” Pomerantsev explains. “The idea that chaos is growing because of the war undermines their entire worldview.”

Why facts bounce off

Delmer worked with Cambridge’s first professor of psychoanalysis to understand Nazi psychology. They identified three elements that make authoritarian propaganda work:

- Identification with the leader – Leaders who normalize aggression, sadism, and narcissism, creating what Pomerantsev calls “a carnival of evil feelings”

- Toxic collective identity – A sense of superiority over others based on supremacism

- Ersatz agency – The illusion of control when people actually have none

“The less control we have over our lives, the more propaganda we need,” Pomerantsev quotes Delmer as observing.

This explains why showing Russians their casualties backfires. In an authoritarian mindset, those deaths demand vengeance, not reflection. Appeals to humanity assume a moral framework that propaganda has already dismantled.

“It’s not that he didn’t believe in facts. He just wanted to find the facts that worked for his aims,” Pomerantsev notes about Delmer’s approach.

The same principle applies today: effective counter-propaganda uses real information, but selects facts that serve strategic goals rather than moral ones.

“I don’t think there’s an important democratic movement in Germany to support,” Delmer concluded about Nazi Germany.

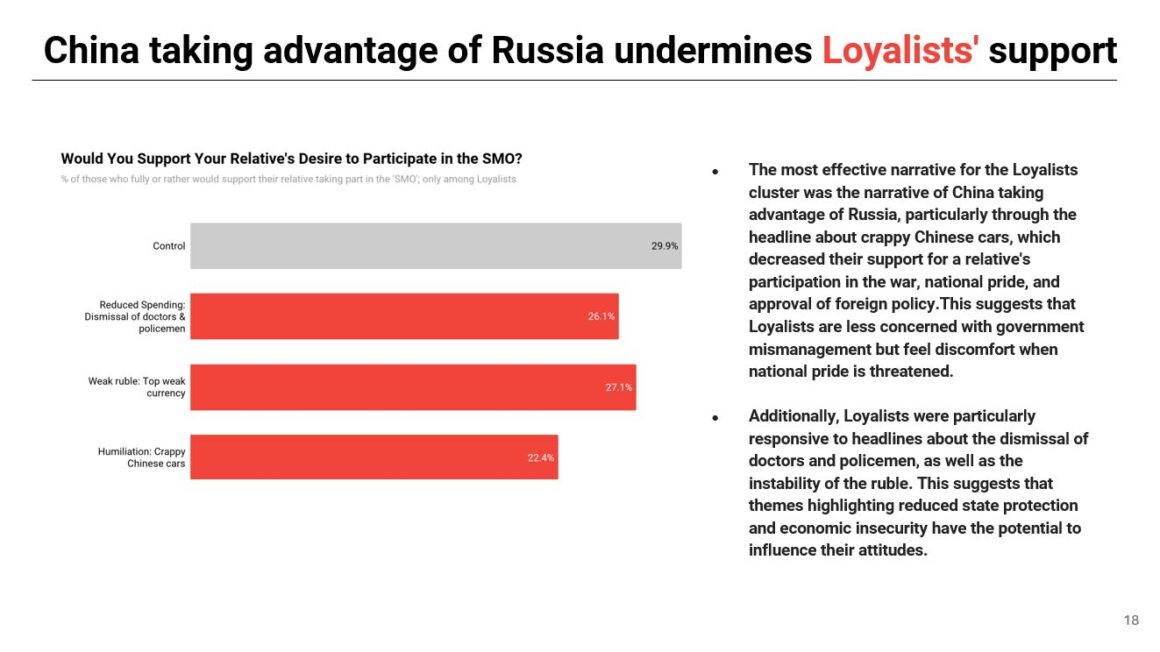

The same pragmatism should guide effective operations against Russia today. As opposed to the current Western strategy of supporting Russian opposition media, which can influence only 11% of critically-minded Russians, disruptive propaganda operations should focus on themes that resonate with authoritarian mindsets rather than moral appeals.

Pomerantsev’s research reveals the psychological mechanism behind this.

Working with teams in Russia, he found “the largest correlation between being ready to send your kids to die in the war is to do with belief in Russian supremacism”—the conviction that Russia is superior to others while simultaneously being victimized by them.

When Russians are primed with messages reinforcing this supremacist-victim narrative, their support for war actually increases. However, other messages do work: those hinting at rising crime inside the army and China humiliating Russia.

It is precisely these kind of messages that Ukraine is using in successful offensive propaganda operations against Russia, Pomerantsev suggests, hinting at the presentation of his book in Kyiv that the Delmers of today are sitting in the room, incognito.

The resource problem

The tragedy is that Ukraine knows what works but lacks the resources to scale it.

“Delmer had the backing of a state which allowed him to experiment,” Pomerantsev points out. “He had a team of hundreds of people working in this beautiful vast country estate outside of London. He managed to persuade the government to give him the most powerful radio transmitter in the world.”

Ukraine has no such luxury. While fighting for survival, it can barely manage domestic information space, let alone mount the massive multimedia campaign needed to truly destabilize Russian mobilization.

“If we were fighting this war as we did the war on terror, we would have set up dozens of radio stations like in Afghanistan,” Pomerantsev notes.

“We had huge information operations during our intervention in Iraq. If we were doing this, it would be such a key element of what we were doing. But we want to undermine mobilization, we say we want to slow down Russia’s war machine, and we haven’t done the ABCs of undermining mobilization and military morale. It just shows you how fundamentally pathetic Ukraine’s partners are.”

We say we want to slow down Russia’s war machine, and we haven’t done the ABCs of undermining mobilization and military morale.

The Kremlin’s real fear

What would work if resources were available? Pomerantsev outlines the pressure points that actually worry the Kremlin:

- Putin’s approval rating – Which collapsed to under 60% during Ukraine’s Kursk operation

- Economic stability – The ruble’s weakness, rising short-term loan defaults, a growing credit crisis

- Military compensation – Soldiers’ families not getting paid, creating resentment

- Elite loyalty – Growing mistrust between different power centers

- China’s reliability – Deep anxiety about Beijing potentially abandoning Moscow

“Any attempt to deter Russia has to be linked into their sense of control,” he argues.

The Kremlin’s leadership remains traumatized by how quickly the Soviet system collapsed. When they sense loss of control, they retreat.

The Kursk incursion proved this. Putin’s rating plummeted. The government panicked, posting and deleting contradictory messages. That was the moment to pile on pressure—NATO exercises, shadow fleet blockades, secondary sanctions. Add coordinated information operations targeting those specific vulnerabilities.

Instead, nothing.

Beyond good and evil

Delmer’s approach offends our democratic sensibilities. He promoted desertion, normalized corruption, used pornography to grab attention.

His radio shows were, by his own admission, an exercise in encouraging Germans to be “bad.”

Nazis told Germans they would be good by doing very bad things, while Delmer told Germans to be bad, achieving a very good thing.

“I think we have to think very carefully when we think about good and bad in politics,” Pomerantsev reflects. “If you’re stimulating someone to think for themselves, if you’re provoking them to act for themselves, if you’re provoking them to break through a kind of passivity which has been fed to them by authoritarian propaganda—I think that’s good.”

He sees Delmer’s work as fundamentally liberating:

“I think at the core of it was a deeply anti-authoritarian project because in stimulating people to think and act for themselves, he was giving them a way to break through authoritarian psychology.”

The Nazis used the language of nobility and sacrifice to enable genocide. Delmer used the language of greed and self-interest to stimulate individual thinking. When you’re deserting or stealing from your factory, you’re reclaiming agency from an authoritarian system.

As Pomerantsev puts it:

“The Nazis used the language of noble and the nation and sacrifice in order to enable genocide and rape, while Delmer was using the language of naughtiness, greed, corruption, sexual hanky-panky in order to stimulate good.”

The inversion is profound: Nazis told Germans they would be good by doing very bad things, while Delmer told Germans to be bad, achieving a very good thing.

This isn’t about making Russians good people. It’s about making them bad soldiers.

Radio then, full-spectrum now

If Delmer were alive today, he wouldn’t pick just one channel.

“We live in a multimedia age, so you need everything and you need scale,” Pomerantsev explains. “You’d be using radio, you’d be using satellite TV where it’s relevant, some of the great things the Ukrainians do—hacking into Russian local TV and playing content. You want all of those. You want to have a sense that you’re everywhere. Robo calls, SMSs, everything. You’re using everything and you’re thinking how they work together to create a full spectrum movement.”

The aim is the same as in the 1940s: make the people who keep the war going feel it’s no longer in their interest. Delmer did it by embracing the “baddie baddie” role. Pomerantsev is asking if Ukraine’s partners are ready to do the same.

As Pomerantsev puts it: “The Ukrainians are doing a lot, and I think, like with Delmer, we’ll find out after the war.”

The question is whether Ukraine’s partners will provide the resources for a real information offensive before it’s too late. Because knowing what works means nothing if you can’t execute it at scale.

Facts don’t defeat propaganda. But appealing to fear, greed, and self-preservation might. Delmer knew it. Ukraine has proven it.

The pig dog is waiting.

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

What We Know About the C.D.C. Shooting in Atlanta

A gunman who believed the Covid-19 vaccine had made him ill fired at the agency’s Atlanta offices, killing a police officer and rattling the public health community.

What We Know About the C.D.C. Shooting in Atlanta

© Elijah Nouvelage/Getty Images

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

C.D.C. Workers Say Shooting Manifests Worst Fears About Anger Among Public

Employees expressed horror at a shooting at the agency’s headquarters, and some said they viewed it as part of a pattern of threats and assaults on health workers.

C.D.C. Workers Say Shooting Manifests Worst Fears About Anger Among Public

© Megan Varner/Reuters

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

Ousted F.D.A. Vaccine Chief Returns to Agency

Dr. Vinay Prasad’s rehiring was an unusual instance of a federal official targeted by the right-wing activist Laura Loomer being brought back into the Trump administration.

Ousted F.D.A. Vaccine Chief Returns to Agency

© U.S. Food and Drug Administration, via Associated Press

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

Gunman in Deadly C.D.C. Shooting Fixated on Covid Vaccine, Officials Say

The shooting in Atlanta, which killed a police officer, followed the spread of false information around Covid vaccines and animosity directed at the agency, public health workers say.

Gunman in Deadly C.D.C. Shooting Fixated on Covid Vaccine, Officials Say

© Megan Varner/Reuters

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

Trump Just Shrugs as Kennedy Undermines His Vaccine Legacy

President Trump’s laissez-faire approach is notable, given that the development of the Covid vaccine was seen as one of his first term’s most notable achievements.

Trump Just Shrugs as Kennedy Undermines His Vaccine Legacy

© Eric Lee for The New York Times

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

Trump Fires Official Over Jobs Report, Echoing an Authoritarian Playbook

In firing the head of the agency that collects employment statistics, the president underscored his tendency to suppress facts he doesn’t like and promote his own version of reality.

Trump Fires Official Over Jobs Report, Echoing an Authoritarian Playbook

© Haiyun Jiang/The New York Times

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

Laura Loomer Attack on West Point Appointee Reflects Larger Fight Over Trump

Jen Easterly, who had served in Republican and Democratic administrations, was headed to the academy. Then a right-wing activist stepped in.

Laura Loomer Attack on West Point Appointee Reflects Larger Fight Over Trump

© Ben Curtis/Associated Press

-

NYT > U.S. News

-

‘Clinton Plan’ Emails Were Likely Made by Russian Spies, Declassified Report Shows

An annex to a report by the special counsel John H. Durham was the latest in a series of disclosures about the Russia inquiry, as the Trump team seeks to distract from the Jeffrey Epstein files.

‘Clinton Plan’ Emails Were Likely Made by Russian Spies, Declassified Report Shows

© Samuel Corum for The New York Times

-

NYT > World News

-

No Proof Hamas Routinely Stole U.N. Aid, Israeli Military Officials Say

Israel has long restricted aid to Gaza on the argument that Hamas steals it to use as a weapon of control over the population. On Saturday, the Israeli military announced new airdrops of aid.

No Proof Hamas Routinely Stole U.N. Aid, Israeli Military Officials Say

© Saher Alghorra for The New York Times

-

Coda Story

-

AI, the UN and the performance of virtue

I was invited to deliver a keynote speech at the ‘AI for Good Summit’ this year, and I arrived at the venue with an open mind and hope for change. With a title “AI for social good: the new face of technosolutionism” and an abstract that clearly outlined the need to question what “good” is and the importance of confronting power, it wouldn’t be difficult to guess what my keynote planned to address. I had hoped my invitation to the summit was the beginning of engaging in critical self-reflection f

AI, the UN and the performance of virtue

I was invited to deliver a keynote speech at the ‘AI for Good Summit’ this year, and I arrived at the venue with an open mind and hope for change. With a title “AI for social good: the new face of technosolutionism” and an abstract that clearly outlined the need to question what “good” is and the importance of confronting power, it wouldn’t be difficult to guess what my keynote planned to address. I had hoped my invitation to the summit was the beginning of engaging in critical self-reflection for the community.

But this is what happened. Two hours before I was to deliver my keynote, the organisers approached me without prior warning and informed me that they had flagged my talk and it needed substantial altering or that I would have to withdraw myself as speaker. I had submitted the abstract for my talk to the summit over a month before, clearly indicating the kind of topics I planned to cover. I also submitted the slides for my talk a week prior to the event.

Thinking that it would be better to deliver some of my message than none, I went through the charade or reviewing my slide deck with them, being told to remove any reference to “Gaza” or “Palestine” or “Israel” and editing the word “genocide” to “war crimes” until only a single slide that called for “No AI for War Crimes” remained. That is where I drew the line. I was then told that even displaying that slide was not acceptable and I had to withdraw, a decision they reversed about 10 minutes later, shortly before I took to the stage.

Looking at this year’s keynote and centre stage speakers, an overwhelming number of them came from industry, including Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon. Out of the 82 centre stage speakers, 37 came from industry, compared to five from academia and only three from civil society organisations. This shows that what “good” means in the "AI for Good" summit is overwhelmingly shaped, defined, and actively curated by the tech industry, which holds a vested interest in societal uptake of AI regardless of any risk or harm.

“AI for Good”, but good for whom and for what? Good PR for big tech corporations? Good for laundering accountability? Good for the atrocities the AI industry is aiding and abetting? Good for boosting the very technologies that are widening inequity, destroying the environment, and concentrating power and resources in the hands of few? Good for AI acceleration completely void of any critical thinking about its societal implications? Good for jumping on the next AI trend regardless of its merit, usefulness, or functionality? Good for displaying and promoting commercial products and parading robots?

Any ‘AI for Good’ initiative that serves as a stage that platforms big tech, while censoring anyone that dares to point out the industry’s complacency in enabling and powering genocide and other atrocity crimes is also complicit. For a United Nations Summit whose brand is founded upon doing good, to pressure a Black woman academic to curb her critique of powerful corporations should make it clear that the summit is only good for the industry. And that it is business, not people, that counts.

This is a condensed, edited version of a blog Abeba Birhane published earlier this month. The conference organisers, the International Telecommunication Union, a UN agency, said “all speakers are welcome to share their personal viewpoints about the role of technology in society” but it did not deny demanding cuts to Birhane’s talk. Birhane told Coda that “no one from the ITU or the Summit has reached out” and “no apologies have been issued so far.”

A version of this story was published in the Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post AI, the UN and the performance of virtue appeared first on Coda Story.

-

NYT > World News

-

Macrons Sue Candace Owens, Accusing Her of Defamation

The suit seeks damages after the podcaster claimed Brigitte Macron is a man. The French president and his wife said the statement caused “pain to us and our families.”

Macrons Sue Candace Owens, Accusing Her of Defamation

© Pool photo by Gonzalo Fuentes

-

Coda Story

-

Resisting the Authoritarian Playbook in the South Caucasus

Recent events in the South Caucasus show how the authoritarian playbook is exported and adapted to suit local contexts. From Armenia’s clergy allegedly plotting coups, to Azerbaijan raiding Russian state-funded media offices as retribution, to Georgia’s mass arrests of opposition leaders, the region revealed how authoritarianism and resistance to it adapts and spreads through digital-age tactics. The three nations of the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, have long occupied a

Resisting the Authoritarian Playbook in the South Caucasus

Recent events in the South Caucasus show how the authoritarian playbook is exported and adapted to suit local contexts. From Armenia’s clergy allegedly plotting coups, to Azerbaijan raiding Russian state-funded media offices as retribution, to Georgia’s mass arrests of opposition leaders, the region revealed how authoritarianism and resistance to it adapts and spreads through digital-age tactics.

The three nations of the South Caucasus: Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, have long occupied a place of strategic and symbolic importance for Russia. The region is a vital transit corridor linking Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, making it a coveted prize for energy routes and geopolitical influence. For Moscow, the South Caucasus has always been more than a neighboring periphery, it is an enduring obsession. And perhaps more so now, as Russia’s position in the Middle East has weakened following setbacks in Syria and its diminished sway in Iran. Today, the Kremlin’s desire to assert control in the South Caucasus is as strong as ever. Yet in each of these three countries, Moscow’s efforts to shape events and narratives are meeting unprecedented resistance. The divergent responses—ranging from defiance to accommodation—highlight how the authoritarian playbook is being adapted, contested, and exported across the region.

So what constitutes this playbook? Legal weaponization through foreign agent laws, criminalization of dissent with disproportionate penalties, systematic impunity for state violence, economic warfare against independent media, and international narrative manipulation. Below are three examples:

Armenia: Hybrid war and the Kremlin’s shadow

Armenia, once Moscow’s closest ally in the South Caucasus, has openly expressed disillusion with years of Russian inaction during regional crises. Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan now warns of “hybrid actions and hybrid war” from Russian circles, without directly blaming the Kremlin, while the EU and France step in to support his decision to jail clergymen in defence of Armenian democracy. The clerics were accused of plotting a coup. Fingers were also pointed at Russian-Armenian businessman Samvel Karapetyan, the alleged orchestrator. It was, in one analyst’s words. Moscow’s “Ivanishvili 2.0 operation”, a reference to Bidzina Ivanishvili, the billionaire founder and de facto leader of Georgian Dream, Georgia’s ruling party since 2012. Georgian Dream, under Ivanishvili, has steered Georgia in an increasingly illiberal and pro-Russian direction. But for a couple of years now, the Armenian government has been gradually distancing itself from Russia, hedging its bets rather than relying on Moscow to guarantee security. In the aftermath of the alleged coup attempt, Armenia’s Foreign Minister bluntly told Russian officials that they “must treat Armenia’s sovereignty with great respect and never again allow themselves to interfere in our internal affairs.” Pashinyan has of late made conciliatory gestures towards both of Armenia’s arch-rivals, Azerbaijan and Turkey. The loss of Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan — while Russian peacekeepers stood by — largely drove Armenia toward European integration as an existential necessity. Armenia's experience with alleged coup plot, and its possible Russian backing, shows how the playbook adapts to different political contexts, exploiting religious institutions and diaspora networks to destabilize governments that drift from Moscow's orbit.

Azerbaijan: Asserting independence, testing the edges

The raid on Russian state media offices in Baku last week sent an unmistakable message about the limits of Moscow’s influence in the region. The targeting of Sputnik journalists came after violent police action in Russia in which two Azerbaijani nationals were killed, an incident Baku condemned as ethnically motivated. For years, Azerbaijan has been systematically moving out of Moscow’s orbit, growing closer to Turkey and unafraid to assert itself in disputes with Russia. The arrests of Russian journalists represent more than bilateral tensions; they signal how even traditionally Moscow-aligned states now calculate that defying Russia carries fewer costs than submission. Russia’s response — summoning the Azerbaijani ambassador and protesting the “dismantling of bilateral relations” — revealed Moscow’s diminished leverage. Azerbaijan’s confidence stems from military victories in Nagorno-Karabakh, increased energy exports to Europe, and strategic ties with Turkey that provide alternatives to a subservient partnership with Russia. Azerbaijan's bold move illustrates another dimension of the regional dynamic: how countries with strong alternative partnerships can successfully resist Russian pressure tactics, even when those tactics include media warfare and diplomatic intimidation.

Georgia: The authoritarian laboratory

Georgia presents the starkest illustration of both the Kremlin’s enduring shadow and the systematic deployment of authoritarian tactics. The ruling Georgian Dream party has implemented what Transparency International calls a “full-scale authoritarian offensive,” with eight opposition figures jailed in just a single week. The crackdown follows months of mass protests against the foreign agent law — a carbon copy of Russian legislation designed to crush civil society. Among those arrested is Nika Gvaramia, the former head of the country’s leading opposition TV channel, who spent a year in prison, received the Committee to Protect Journalists’ International Press Freedom Award, and emerged to found his own political party. Now Gvaramia faces another eight-month sentence plus a two-year ban from holding office, an example of how the repressive state systematically eliminates viable opposition while maintaining a veneer of legal process.

The foreign agent law itself has become a remarkably successful Russian export — a tool used from Nicaragua to Egypt to stigmatize independent civil society as “trojan horses” serving foreign interests. In Georgia, the law forces organizations receiving over 20% foreign funding to register as entities “pursuing the interests of a foreign power,” enabling harsh monitoring requirements and the systematic isolation of critics.

Since Russia pioneered the foreign agent model in 2012, it has been adopted by countries including Nicaragua, where it has been used to shut down over 3,000 civil society organizations, and Hungary, where officials explicitly cited the US FARA law as justification when facing international criticism. The model's appeal to authoritarian leaders lies in its appearance of legitimacy — claiming to mirror democratic precedents while systematically dismantling civil society. The chilling effect extends beyond legal restrictions.

Physical attacks on journalists have become routine, with not a single perpetrator facing accountability. Instead, the state's message is unmistakable: challenge us, and you will pay. According to the 2025 World Press Freedom Index, economic pressure has become a critical threat to media freedom globally, with the economic indicator hitting an “unprecedented, critical low” of 44.1 points — Georgia exemplifies this trend through its systematic economic warfare against independent outlets.

Mzia’s story

The story of one Georgian journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli, founder of two independent newsrooms Batumelebi and Netgazeti, is a textbook case of how modern authoritarianism operates through seemingly proportional responses to manufactured crises.

Amaglobeli was taken into custody for placing a solidarity sticker reading “Georgia goes on strike” and subsequently slapping Police Chief Irakli Dgebuadze after hours of degrading treatment, including watching colleagues being beaten by police.

Amaglobeli was arrested for assaulting a police officer, but many suspect her journalism was the real target. The charges against Amaglobeli — from “distorting a building’s appearance” for the removable sticker to “attacking an officer” — could mean seven years in prison. Evidence has been manipulated, timelines don’t match, and the authorities’ narrative shifts with each wave of international criticism. During detention, she was subjected to degrading treatment — insulted, spat upon, and denied access to water and toilets.

“It’s not only her being on trial, it’s independent media being on trial in Georgia,” said Irma Dimitradze, Amaghlobeli’s colleague who is now leading the global campaign to free her. She was speaking at Coda’s annual ZEG Fest along with Jodie Ginsberg, CEO of the Committee to Protect Journalists; human rights barrister Caoilfhionn Gallagher, and Nobel laureate and co-founder of Rappler Maria Ressa. All three argued that the systematic nature of the persecution of Amaglobeli reveals the broader strategy that’s similar the world over. Her case demonstrates how authoritarian systems create conditions where any human response to injustice becomes criminal evidence.

As Caoilfhionn Gallagher put it: “You are not dealing here with a rule of law compliant system... there’s a whole series of absolutely farcical things which have happened in this case so far. The criminal investigation was headed by the officer who was the alleged victim. I mean these are…you couldn’t make this stuff up, really... it is clear that in Georgia you are not going to get a fair trial. She hasn’t had due process yet and really what's going to make the difference here is ensuring that the world is watching and that there's a proper international strategy.”

After a 38-day hunger strike, Amaglobeli remains defiant, standing for hours in court, refusing to sit, determined to show she cannot be broken. Her symbolic gesture of holding up Ressa’s book, “How to Stand Up to a Dictator”, during court appearances has become an icon of resistance.

“We know,” said Ressa, “that journalism around the world is under attack.” With 72% of the world’s population living under authoritarian rule, added Ressa, “the time to protect our rights is now.” Gallagher spoke about the “power of international solidarity,” how what authoritarians fear is “journalism with a purpose, with an editorial line which is designed to undermine the false narratives and the gaslighting on a grand scale.”

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

Related Articles

The post Resisting the Authoritarian Playbook in the South Caucasus appeared first on Coda Story.

-

The Kyiv Independent

-

Argentina says it uncovered Russian spy network linked to late Prigozhin's group

Argentina has uncovered a Russian intelligence operation working to spread pro-Kremlin disinformation and influence public opinion, Argentine presidential spokesperson Manuel Adorni announced on June 18, citing the country's intelligence, according to AFP and Infobae.The La Compania network, which is allegedly linked to the Russian government and the Kremlin's Project Lakhta, was led by Russian nationals Lev Konstantinovich Andriashvili and his wife Irina Yakovenko, who are both residents of Arg

Argentina says it uncovered Russian spy network linked to late Prigozhin's group

Argentina has uncovered a Russian intelligence operation working to spread pro-Kremlin disinformation and influence public opinion, Argentine presidential spokesperson Manuel Adorni announced on June 18, citing the country's intelligence, according to AFP and Infobae.

The La Compania network, which is allegedly linked to the Russian government and the Kremlin's Project Lakhta, was led by Russian nationals Lev Konstantinovich Andriashvili and his wife Irina Yakovenko, who are both residents of Argentina, according to authorities.

The U.S. Treasury Department has previously accused the Project Lakhta, reportedly formerly overseen by late Russian oligarch Yevgeny Prigozhin, of election interference in the United States and Europe.

Prigozhin led the Russian Wagner mercenary group that was deployed in some of the deadliest battles in Ukraine, like the siege of Bakhmut. The oligarch was killed in a plane crash under suspicious circumstances in August 2023, around two months after leading a brief armed rebellion against the Kremlin.

Andriashvili and Yakovenko are accused of receiving financial support to recruit local collaborators and run influence operations aimed at advancing Moscow's geopolitical interests.

Their objective was to "form a group loyal to Russian interests" to develop disinformation campaigns targeting the Argentine state, Adorni said at a press briefing.

The spokesperson added that the alleged operation included producing social media content, influencing NGOs and civil society groups, organizing focus groups with Argentine citizens, and gathering political intelligence.

"Argentina will not be subjected to the influence of any foreign power," Adorni said, noting that while some findings have been declassified, much of the investigation remains a state secret.

Since Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there has been a significant uptick in Russian migration to Argentina, some of which officials fear could be linked to covert intelligence operations.

Authorities reportedly said these espionage activities are often facilitated by a 2009 bilateral agreement between Argentina and Russia allowing visa-free travel, a deal that remains in effect despite growing security concerns.

In response to the threat, Adorni announced the creation of a new Federal Investigations Department (DFI) within Argentina's Federal Police, modeled in part on the U.S. FBI. The agency will focus on countering organized crime, terrorism, and foreign espionage, with investigators trained in advanced techniques and bolstered by experts in law, psychology, and computer science.

The Kyiv IndependentMartin Fornusek

The Kyiv IndependentMartin Fornusek

-

Coda Story

-

Bucharest Calling: MAGA goes on tour

“Russia rejoices,” wrote the pro-European Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk on X this week. He was referring to a joint appearance onstage in Warsaw of George Simion, the far right presidential candidate in Romania, and his Polish equivalent Karol Nawrocki just days before elections in both countries. On May 18, Romanians will vote in the second and final round of elections to pick their president, with Simion, a decisive first round winner, the favourite, albeit current polling shows he is

Bucharest Calling: MAGA goes on tour

“Russia rejoices,” wrote the pro-European Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk on X this week. He was referring to a joint appearance onstage in Warsaw of George Simion, the far right presidential candidate in Romania, and his Polish equivalent Karol Nawrocki just days before elections in both countries.

On May 18, Romanians will vote in the second and final round of elections to pick their president, with Simion, a decisive first round winner, the favourite, albeit current polling shows he is running neck-and-neck with his opponent Nicusor Dan, the relatively liberal current mayor of Bucharest. Also on that day, the first round of Poland’s presidential elections will take place. Nawrocki, analysts suggest, is likely to lose to the more liberal Warsaw mayor Rafał Trzaskowski.

But Simion’s appearance in Warsaw did cause anger, with one Polish member of the European parliament describing both candidates as representatives of “Putin’s international”. Simion denies being pro-Kremlin, but wants to stop military aid to Ukraine. An ultranationalist, he promotes the rebuilding of a greater Romania, raising the prospect of potential territorial disputes with Ukraine, Moldova, and Bulgaria. Indeed, he is already banned from entering both Moldova and Ukraine.

Rather than Russia, the association Simion prefers to acknowledge is with Donald Trump and MAGA. As he said of his visit to Poland and support for Nawrocki, “Together, we could become two pro-MAGA presidents committed to reviving our partnership with the United States and strengthening stability along NATO’s eastern flank.”

Certainly, Simion’s MAGA love was on show during the first round of Romania’s election on May 4, and MAGA reciprocated that love.

At the party’s Bucharest headquarters, on a warm, triumphant election night, with Simion having won over 40% of the votes, a MAGA hat-wearing American took to the podium. He asked the cheering crowd if they wanted their own "Trump hat", and threw one (and only one) towards a section chanting "MAGA, MAGA, MAGA." Brian Brown, a prominent conservative activist, was in his element, expressing solidarity with jubilant Simion supporters.

"You, my friends," he said, "are in the eye of the storm. What happens in this country will define what happens all over Europe. And Americans know it and more and more are waking up to the truth that we must stand together. We must never be silenced." Meanwhile, a protester screaming “fascists” was quickly removed.

Brown, who leads the anti-LGBTQ group International Organization for the Family and has been described by human rights organizations as an "infamous exporter of hate and vocal Putin supporter," was celebrating a seismic political shift. In response to Simion’s large first round victory, Romania's prime minister resigned. His own party's establishment candidate didn’t even make it to the May 18 second round.

Simion, a 38-year-old Eurosceptic and self-described "Trumpist," had founded his far-right nationalist party, Alliance for the Union of Romanians (AUR) just over a decade ago. At the AUR offices on election night – with Simion himself only appearing by video – Brown drew explicit parallels between Romania's situation and that of America, extolling the "friendship of true Romanians and true Americans, people that stand together against a lie." Right wing leaders in other countries echoed the sentiment. Italy's deputy prime minister Matteo Salvini, for instance, declared on social media that Romanians had "finally voted, freely, with their heads and hearts."

Romania's election became a right wing cause célèbre after the Constitutional Court annulled the presidential polls in December last year, ruling that it had been vitiated by a Russian influence operation. U.S. vice president JD Vance accused Romania of canceling the election based on “flimsy suspicions” and Elon Musk described the head of the Constitutional Court as a “tyrant”. This is why MAGA supporters took a keen interest in the May 4 do-over. It was, according to Brown, a litmus test for freedom, for the voters’ right to choose their president, no matter how unpalatable he might be to the establishment.

In November, 2024, far-right candidate Călin Georgescu won the first round of Romania’s presidential elections. The polls were scuppered though after intelligence revealed irregularities in campaign funding and that Russia had been involved in the setting up of almost 800 TikTok accounts backing Georgescu’s candidacy. He was also barred from participating in the rerun.

Distrust and disapproval of Romania’s political system have been growing ever since. When I got to Bucharest, my taxi driver, the first person I met, told me he wouldn’t even bother voting in the rerun. The ban on Georgescu was portrayed in right wing circles as anti-democratic. And the support he received from leading Trump administration figures such as Vance was in keeping with their support for far-right parties across Europe.

Before Friedrich Merz won a contentious parliamentary vote to become German Chancellor, U.S. Secretary of State Marco Rubio said Germany was a “tyranny in disguise” because its intelligence services classified the anti-immigration AfD, now Germany’s main opposition party, as “confirmed right wing extremist[s].” Vance said the “bureaucrats” were trying to destroy “the most popular party in Germany.” It proved, he added, that decades after the West brought down the Berlin Wall, the German establishment had “rebuilt” it. The outspoken nature of this intervention in the internal politics of an ally shows that the Trump administration would rather maintain ideological ties with far-right parties in Europe than follow traditional diplomatic protocols.

Simion, for his part, has said that he’s a natural ally of the U.S. Republican Party, and that AUR is “almost perfectly aligned ideologically with the MAGA movement.” Just two weeks before the Romanian elections, Brian Brown met with Simion and his wife in Washington, D.C., with both men propagating their affinity to “the free world” and “Judeo-Christian legacy” in an Instagram video. Simion is also currently being scrutinized over attempts to hire a lobbying firm in the U.S. for $1.5 million to secure meetings with key American political figures and media appearances with U.S. journalists.

In Romania, the president has a semi-executive role that comes with considerable powers over foreign policy, national security, defence spending and judicial appointments. The Romanian president also represents the country on the international stage and can veto important EU votes – a level of influence that might be considered handy on the other side of the Atlantic too.

The fact that both U.S. and other European far-right leaders came in person to offer their support to Simion after the first round of the election, or paid obeisance online, shows how it’s becoming increasingly important for the far-right to to be seen as a coherent, global force. As Brown put it in Bucharest: “We need MAGA and MEGA. Make America great again. Make Europe great again.”

With Canada and Australia swinging to the center-left in their recent elections – in what many have called “the Trump slump” – the Romanian election offers Trump and MAGA hope that it can continue to remake the world in its own image. The irony is that MAGA, with its global offshoots, is arguably the most effective contemporary international solidarity movement, despite railing against globalism and being so apparently parochial in its outlook.

A version of this story was published in last week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

Related Articles

How to make M.A.G.A. mean ‘Make America Good Again’

Ground Zero of Russian Interference

The post Bucharest Calling: MAGA goes on tour appeared first on Coda Story.

-

Coda Story

-

The Christian right’s persecution complex

Last week, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky spoke to right wing influencer Ben Shapiro, founder of "The Daily Wire". The interview showed how much stock Zelensky puts in speaking to a MAGA and Republican audience. It is with this audience that Zelensky has little credibility and Ukraine little sympathy, as Donald Trump calls for a quick peace deal, even if it means Ukraine ceding vast swathes of territory to the Russian aggressor. Zelensky needs Shapiro to combat conservative apathy about

The Christian right’s persecution complex

Last week, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky spoke to right wing influencer Ben Shapiro, founder of "The Daily Wire". The interview showed how much stock Zelensky puts in speaking to a MAGA and Republican audience. It is with this audience that Zelensky has little credibility and Ukraine little sympathy, as Donald Trump calls for a quick peace deal, even if it means Ukraine ceding vast swathes of territory to the Russian aggressor. Zelensky needs Shapiro to combat conservative apathy about the fate of Ukraine, and combat its admiration and respect for Putin as a supposed bastion of traditional values and religious belief.

Two questions into the interview, Shapiro confronts Zelensky with a conservative talking point. Is Ukraine persecuting members of the Russian Orthodox Church? It is a view that is frequently aired in Christian conservative circles in the United States. Just two months ago, Tucker Carlson interviewed Robert Amsterdam, a lawyer representing the Ukrainian Orthodox Church. Amsterdam alleged that USAID, or some other U.S. government-sponsored organization, created an alternative orthodox church "that would be completely free of what they viewed as the dangerous Putin influence." This, Amsterdam said, is a violation of the U.S. commitment to religious freedom. Trump-supporting talking heads have frequently described Ukraine as killing Christians, while Vladimir Putin is described as a defender of traditional Christian values.

On April 22, Putin met with the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church and Patriarch Kirill, his Russian counterpart. The Serbian Patriarch told the Russian president that when he met with the Patriarch of Jerusalem, the latter said "we, the Orthodox, have one trump card... Vladimir Putin." It was the Serbian Orthodox Church's desire, the Patriarch said, that "if there is a new geopolitical division, we should be... in the Russian world." It is Orthodoxy's perceived political, rather than purely spiritual, link to Russia that the Ukrainian parliament was hoping to sever in August last year by passing legislation to ban religious groups with links to Moscow.

The Russian orthodox church, which is almost fully under Kremlin’s control, is one of Moscow’s most potent tools for interfering in the domestic affairs of post-Soviet countries. Its ties to Russian intelligence are well-documented and run deep. Patriarch Kirill, head of the Russian Orthodox Church, spent the 1970s spying for the KGB in Switzerland. Today, he blesses Russian weapons and soldiers before they’re deployed to Ukraine.

While Christian conservatives in the U.S. accuse Ukraine of violating religious freedoms and "killing" Christians, Zelensky says that it is, in fact, Russian forces that are persecuting Ukrainian Christians. On Easter, Zelensky said 67 clergymen had been "killed or tortured by Russian occupiers" and over 600 Christian religious sites destroyed. I spoke to the Emmy-winning journalist Simon Ostrovsky who said Russia targets Christian denominations.

"If we're talking about an evangelical church," he told me, "then the members of the church will be accused of being American spies. And if we're talking about the Ukrainian Catholic Church, they'll consider it to be a Nazi Church.” But, Ostrovsky added, "Russians have been able to communicate a lot more effectively than Ukraine, particularly to the right in the United States. Russia has been able to. make the case that it is in fact the Ukrainians who are suppressing freedom of religion in Ukraine and not the Russians, which is absurd."

Back in 2013, Pat Buchanan, an influential commentator and former Reagan staffer, asked if Putin was "one of us." That is, a U.S.-style conservative taking up arms in the "culture war for mankind's future". It is a perception Putin has successfully exploited, able to position himself as the lone bulwark against Western and "globalist" decadence. Now with Trump in the White House, propelled there by Christian conservative support, which has stayed steadfastly loyal to the president even as other conservatives question policies such as tariffs and deportations without due process. With the Christian right as Trump's chief constituency, how can he negotiate with Putin free of their natural affinity for the president not just of Russia but arguably traditional Christianity?

The battle over religious freedom in Ukraine is not just a local concern – it’s a global information war, where narratives crafted in Moscow find eager amplifiers among U.S. Christian conservatives. By painting Ukraine as a persecutor of Christians and positioning Russia as the last defender of “traditional values,” the Kremlin has successfully exported its cultural propaganda to the West. This has already had real-world consequences: shaping U.S. policy debates, undermining support for Ukraine, and helping authoritarian leaders forge alliances across borders. The case of Ukraine shows how religious identity can be weaponized as a tool of soft power, blurring the line between faith and geopolitics, and revealing how easily domestic debates can be hijacked for foreign influence. In a world where the persecutors pose as the persecuted, understanding how narratives are manipulated is essential to defending both democracy and genuine religious freedom.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

The post The Christian right’s persecution complex appeared first on Coda Story.