Burning fields, empty trucks, and one lifeline cut: Russia’s drone safari turns into siege of Kherson

Driving past the Kherson Oblast Sign without a drone detector is too dangerous—Russian drone attacks have made the M-14 highway a killing ground for civilians. So I hop off the minivan and wait for a special ride.

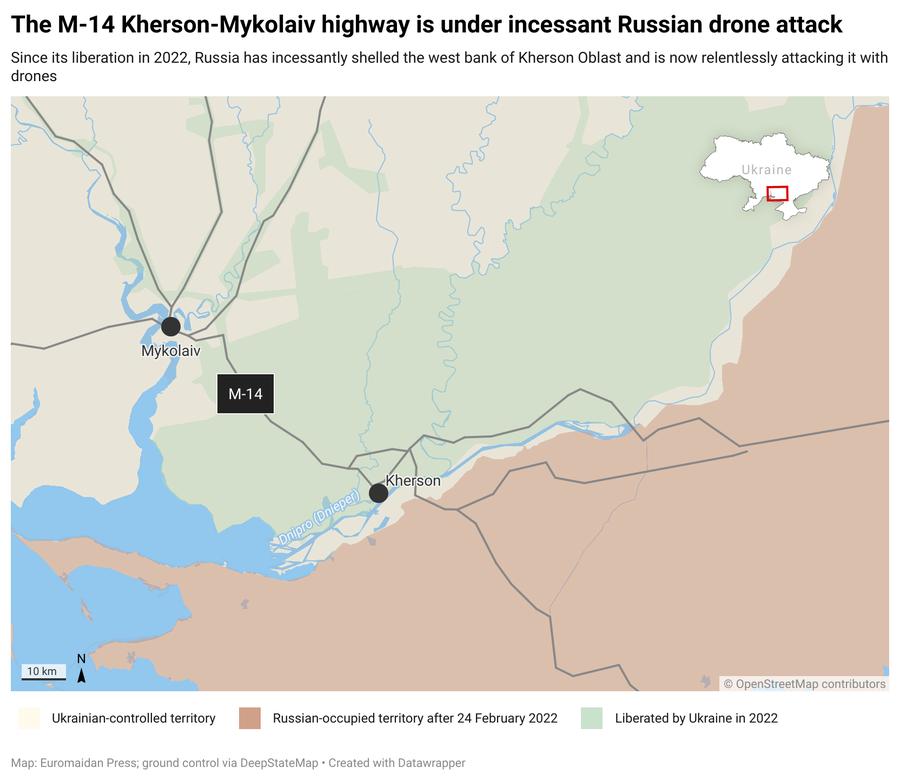

The M-14 Kherson-Mykolaiv highway has been under non-stop Russian drone attacks for the last two months, until it was temporarily closed on 27 August 2025.

Russian drones force closure of key Ukraine highway

The windows of the gas station on the side of the road are covered with plywood, a signature style of Kherson, the city of “wooden windows.” The glass has long been shattered due to Russian drone attacks.

The Russians did not take Ukraine’s 2022 liberation of the city of Kherson and the west bank of the Dnipro lightly. They took revenge by relentlessly pummeling civilian homes, shops, and distribution points with artillery from across the river.

But artillery can reach only so far. As the Russo-Ukrainian war became increasingly dominated by drones, the Russians found ways to make their terror more effective—through a “drone safari” on civilians.

With all the recent innovations and tricks, first-person view (FPV) drones can fly almost 30 km inland, and many new types are quickly added.

My eyes are tearing up as I see my friend’s car zooming towards me at a Hollywood thriller speed. The air is filled with soot and dust. Fires are blazing in the bright-yellow, dry fields on both sides of the highway. Black smoke covers the sky over a tractor crawling along the smoldering, burnt soil.

New AI-controlled drones evade detection systems

My friend Volodymyr throws my backpack with a bulletproof vest and helmet in the trunk, I hop in, and off we fly—still slower than a couple of cars swishing by at 120—150 km/hour to avoid drone attacks. A jeep with metallic rectangular devices on top speeds ahead, and Volodymyr says, “We should be moving that fast, but we got the stuff.”

He points at the two drone detectors: one, a black square the size of a soapbar, called Aracchis, starts beeping if a drone is close. The other, Hover, bigger, and with a screen, catches the video signal from the Russian drone.

“Can they see every single drone?” I ask.

“Not the AI-controlled ones. There is one called zhdun—’the one that waits.’ Those run on fiber optic, and they land and sit by the side of the road, waiting for the target they are programmed to attack. Detectors also can’t see regular fiber optic drones—but we will surely see it if it approaches us.”

Both devices burst with high-pitched beeps like some hungry birdlings in a sick nest. Hover’s silver screen is trembling and blinking, meaning the Russian drone is close by, but we are driving so fast that we get away from the drone, so I don’t get to see myself the way the Russian pilot sees me before dropping explosives on me.

At this point, we dive into a “drone tunnel.” It is an odd structure made of tall poles holding fishing nets billowing in the wind.

Inside this surreal tunnel, the car twists and turns around a smashed minivan, its front a black metallic mess, with a sign “well drilling” on its side. On the other side of the road, a small red sedan sits upside down in a ditch, wheels still spinning.

The fields on both sides are burning. The torn fishing net is flowing like a gauze theater curtain. Russian drones destroyed these cars just a few minutes ago. The tunnel didn’t help.

“The priority for Russian drones is bigger vehicles: trucks, minivans. But if a drone is running low on battery, it will attack us and anything that moves.”

Driving to and from Kherson amid drone strikes, Elvina felt composed and even took a video—but she asks, “Why?”

— Zarina Zabrisky

Khersonians learned to live as human safari rages in their city, drones hunting them from above.

“Human safari” is the only way to call it. pic.twitter.com/RtpYjtNSTu(@ZarinaZabrisky) August 29, 2025

We drive through more tunnels and into the city, where the air becomes toxic, smelling of something like ammonia, and creeps under my skin.

I drop my backpack and head to see my friend Svitlana, who just joined the army and is about to leave her rented studio in Kherson. Her family’s house by the river burned down after an attack. Russian artillery shells killed her husband and mother.

Her son is in the army, but his 20-something wife, three-year-old daughter Stesha, and Svitlana’s teenage daughter share the matchbox-size apartment with her, along with four cats and a pet hedgehog. The young women look sad and lost, but Stesha is jumping on the bed—there is no place on the floor.

“I saw a plane!” she shouts.

Planes have not been flying in Ukraine since the start of the full-scale invasion.

Russians killed her mother and husband and burned her house. Her father couldn’t stand it and died of a heart attack. Her son is a soldier and she has joined the army, to defend her girls.

— Zarina Zabrisky

Meet Phoenix.

Svitlana is featured in our documentary Kherson: Human Safari. pic.twitter.com/7XCZWQ9mo9(@ZarinaZabrisky) September 14, 2025

“We tell her that planes are flying by when we hear aerial bombs and explosions,” says Svitlana. “We saw Russian helicopters dropping something like chemicals.”

She’s already packed to leave. Shelling outside never stops. We hug, and I go back to my neighborhood, downtown Kherson.

Kherson’s symbolic heart lies in ruins

In the heart of the city, at Freedom Square, the ruins of the White House remind me of a burial mound. I remember that there was, in fact, a Scythian burial mound here once. Seeing these creamy blocks of concrete and stone, torn wires sticking out, physically hurts.

The White House was the first building I saw in Kherson after its liberation in November 2022. As the doors of the press tour bus opened, I saw the rectangular classic palace—it seemed to be floating, suspended in the sky like an elegant wedding cake, filled with joy, happiness, and promise. The air then smelled like freedom.

Now, it smells of death and threat—and something like ammonia.

Inside Human Safari: the film that captures Russia’s drones hunting Ukrainians like prey

In June 2025, the Russian military dropped four guided aerial bombs on the White House, and the façade collapsed. Behind the debris, though, a young green tree is breaking through the rubble, leaves trembling in the breeze.

Russian forces openly target civilians in “human safari”

I check a Russian Telegram channel close to the military: it helps to know what they are up to. Usually, it shares neon-colored aerial videos taken by drones used to hunt civilians, accompanied by cheerful tunes.

Today, it posted a grainy video of explosives dropped on a man walking a big white dog. Both the man and the dog are injured and bleeding. The man, visibly in shock, is dragging his dog somewhere, perhaps to safety, when the video stops.

“We pity no one,” reads the caption. “Do not whine.”

The channel continues posting threats throughout the day, “Leave the area. Every moving object is a target.”

— Zarina Zabrisky

“We pity no one,” says a caption to this video.

A Russian drone drops explosives on a man walking his dog in Kherson suburb.

Visibly in shock, the man keeps walking, dragging the injured dog after him.

The video is shot/shared by Russians on Telegram, w/ a Russian pop song pic.twitter.com/ZOx8cXseXD(@ZarinaZabrisky) August 25, 2025

The next day, the same channel announces that every vehicle on the road to Mykolaiv is a “legitimate target.”

Supply routes to 60,000 Kherson residents under threat

In the evening, two cars are hit by Russian drones. Several civilians are injured. The next morning, three more cars are hit and burned down, and the local administration announces that the highway will be partially shut down in case of the presence of the drones and asks to look for alternative routes.

The problem is that the alternative routes do not really exist. The ones that do are located so close to M14 that they are as dangerous. Some dirt roads go through the mined fields, and most trucks or passenger cars cannot pass through there.

In my corner grocery store, shelves are still filled with local peaches, grapes, and plums, as well as candies and bread. Some goods are missing as the truck drivers refuse to drive downtown Kherson.

Hi, I’m Zarina, a frontline reporter for Euromaidan Press and the author of this piece. We aim to shed light on some of the world’s most important yet underreported stories. Help us make more articles like this by becoming a Euromaidan Press patron.

“It is not an issue yet,” says the saleslady. “We bring eggs and mineral water from a ‘safer’ neighborhood or from the big store that runs its own delivery.”

Yet, once the road is closed, how long will these supplies last? 60,000 civilians are still living in Kherson.

By a café, a three-year-old and his mother are blowing bubbles to the sounds of explosions, thin, filmy surface reflecting the blue sky. A group of teenagers, hair dyed, meander down the alley, looking bored and aloof, like all teenagers in the world.

Yet, many have left. Vlada, a young mother from the yard next to mine, is no longer there because the fun garden she kept for her son is overgrown with weeds. The plastic ships and duck in the dried pond are faded from sitting in the sun all summer long. The armchair is torn and broken. Dead pigeons are spread on the ground, and I am not sure why: chemicals, shrapnel, pecking glass dust? Or no one to pick them up?

The leaves on the trees are rusty-red and are already falling.

“Watch your step!” shouts my neighbor. “Mines!”

Life continues under constant drone surveillance

Once the trees are bare, there is no more place to hide—and this year, “human safari” is more brutal than last year.

With AI-operated and fiber optic drones, as well as new tactics—swarm of drones, and bigger drones carrying baby-killer-drones—drone warfare turns into a nightmarish sci-fi horror flick on steroids that the UN has deemed a crime to humanity.

Here and there downtown, the streets are protected with fishing nets, so the city starts turning into a drone tunnels labyrinth, as if a giant spider is weaving its web over Kherson. The thin threads are glistening in the sun, and the glass from shattered windows is sparkling on the broken asphalt.

Kherson is still alive, and on Independence Day, people in vyshyvankas, with elaborate hairdos and perfect manicures, are singing the Ukrainian anthem and patriotic songs in bomb shelters.

Checking the sky for drones and the road for mines, I run around the city. To a rock concert in a basement, with a drone making an appearance in the intermission. To a working library in the dilapidated building hit several times.

Despite daily horrors, Ukrainians are defending their identity and culture.

— Zarina Zabrisky

A report from a damaged library in Kherson, still offering theater classes for kids under fire.

I will be reporting from a theater and arts festival in Kherson and Mykolaiv this week. pic.twitter.com/siXIie4UoO(@ZarinaZabrisky) September 16, 2025

To my yoga studio, where the instructor Jane laughs and shows me how to hang upside down from the fly—with her palm marked by red stitches healing from a drone injury.

My friends text and ask if I am going to a poetry reading in Mykolaiv this weekend. I remember the burning road, cars aflame, and the fact that this week, I could not get a ride out of town.

I have cancelled my trip to Paris for my documentary film premiere, and not just because the road is now closed. There is still a train going to Kyiv, and I can get out, but I want to go to a poetry reading with my Kherson friends.