“Russian spies” who justified Ukraine’s anti-corruption crackdown nowhere to be found

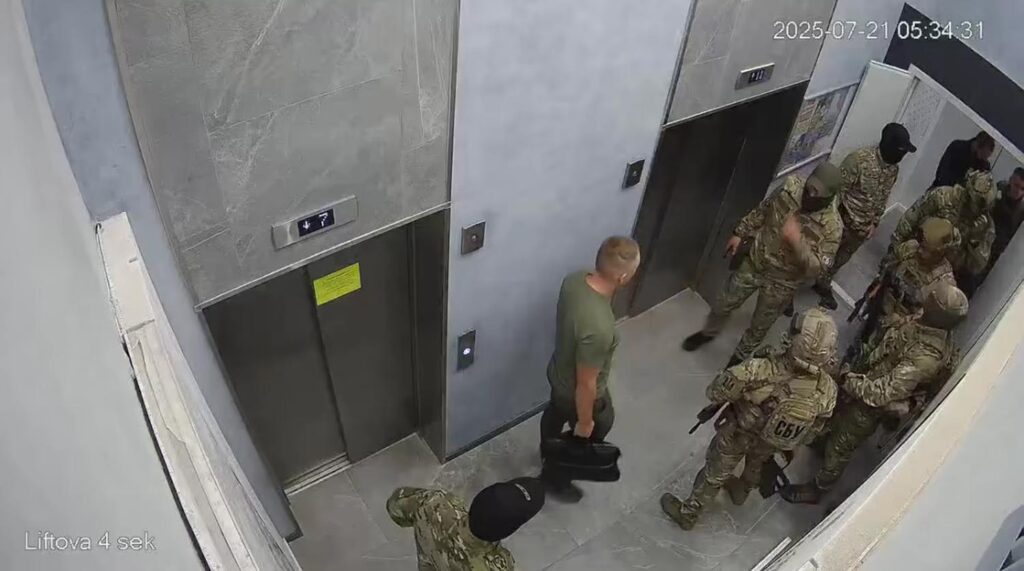

On 21 July 2025, Ukraine’s Security Service made dramatic claims: the country’s top anti-corruption agencies were plagued with Russian infiltrators. Simply devastating during wartime—Russian spies had penetrated the National Anti-Corruption Bureau and Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office, threatening national security at its core.

The next day, parliament rushed through Law No. 12414, bringing both agencies under control of the prosecutor general. Despite protests flaring across Ukrainian cities, Zelenskyy promptly signed the legislation. “The anti-corruption infrastructure will work, NABU and SAPO will work,” Zelenskyy declared that evening, “but without Russian influences that had to be removed.”

Nobody explained how unprecedented prosecutorial control over independent bodies would decrease supposed Russian control within them.

But here’s the greatest catch: nearly all claims of Russian influence appear to fall apart under scrutiny, according to Ukrainska Pravda’s latest investigation.

The justification for dismantling a decade of anti-corruption infrastructure? It’s crumbling two weeks later.

Ukraine anti-corruption investigators targeted, evidence missing

Ukrainska Pravda’s investigation reveals how surprisingly weak the actual proof remains. The outlet interviewed multiple sources to examine what investigators actually found versus what they claimed.

The case against Viktor Gusarov centers on allegations he provided classified information to a former Yanukovych-era security official while working in NABU’s elite D-2 unit. The Security Service claims to have documented “at least 60 instances” of information transfer to Russian intelligence.

But when NABU requested evidence about Gusarov’s alleged crimes in July, “they haven’t received an answer to this day,” Ukrainska Pravda reports.

The investigation into Ruslan Magamedrasulov involves his family’s hemp business, which the Security Service alleges was used for illegal exports to Russia. Authorities arrested over 100 tons of technical hemp they claimed was “ready for shipment to Dagestan.”

Olena Shcherban, Magamedrasulov’s lawyer, told Ukrainska Pravda the hemp business was entirely legal—producing tea, oils, and dietary supplements sold only within Ukraine. She suspects the Security Service’s audio recordings were “glued together from cuts of different conversations” and plans to request the original recordings.

Several targeted NABU employees faced searches simply for having relatives in occupied territories with Russian passports—a situation affecting millions of Ukrainian families divided by Russia’s 2014 invasion.

NABU detectives handling Zelenskyy inner circle cases targeted

Here’s what actually happened: the operation focused on investigators handling cases involving Zelenskyy’s inner circle.

Magamedrasulov “participated in documenting the activities” of Timur Mindich, Zelenskyy’s business partner from Kvartal-95 studio. Sources told Ukrainska Pravda the targeting of regional NABU leadership was specifically connected to the Mindich case.

Detective Ivan Kravchuk was handling the case against former Agriculture Minister Mykola Solskyy, who was forced to resign due to NABU’s investigation.

Detective Oleksandr Skomar was running the case against former Deputy Prime Minister Oleksiy Chernyshov—Zelenskyy’s birthday party guest during COVID lockdown.

And here’s where the pieces connect: Prosecutor General Ruslan Kravchenko’s priority task, appointed just one month before the operation, was to neutralize NABU’s case against Chernyshov, according to Ukrainska Pravda’s earlier reporting.

The pattern becomes clear when examining who faced the heaviest scrutiny—not abstract security threats, but investigators probing the president’s personal network.

Security Service sources doubt operation

Even within the Security Service, doubts emerged.

“Sources in several law enforcement agencies emphasize that doubts exist within the Security Service itself not only regarding such verdicts, but also the validity of such suspicions,” Ukrainska Pravda reports.

Most tellingly, sources said anti-corruption agency leaders demanded Zelenskyy either “publicly justify the Security Service’s actions and accusations, or release the employees.”

EU freezes billions as evidence crumbles

The weak evidence helps explain why the operation became the final straw for international partners. The European Union froze $1.7 billion in aid immediately after the controversial law passed, with another $3.8 billion hanging in the balance.

For Brussels, this wasn’t just about one law. European officials had already flagged structural problems with Ukraine’s anti-corruption policy during an 11 July 2025 subcommittee meeting, weeks before the controversial legislation.

Civil society forces complete retreat

What Ukrainian authorities didn’t anticipate was civil society’s strength. Within hours of the law passing, mass demonstrations erupted across Kyiv, Lviv, Dnipro, and Odesa—the largest protests since Russia’s invasion began.

Teenagers and young adults led chants, organizing through social media, holding signs comparing Zelenskyy to fugitive dictator Viktor Yanukovych. A generation that grew up after Euromaidan was showing that Ukraine’s democratic transformation had become irreversible.

After 10 days of street pressure and international condemnation, parliament voted 331-0 to restore anti-corruption agency independence on 31 July.

Broader institutional pressure continues

The anti-corruption operation wasn’t isolated. Even after July’s retreat, the administration continued efforts to control oversight bodies through other means.

Ukraine’s Cabinet finally appointed Oleksandr Tsyvinskyi as director of the Bureau of Economic Security on 6 August 2025, ending weeks of obstruction that risked $2.3 billion in IMF funding. Tsyvinskyi had won the official selection process unanimously in July, but the appointment stalled amid unsubstantiated security concerns about his Russian-born father—the same playbook used against other qualified investigators.

Ukraine caves under $ 2.3 bn threat, appoints investigator it desperately wanted to block

Media under pressure

The investigation takes on added significance given Ukrainska Pravda’s own pressure campaign. Editor-in-chief Sevgil Musayeva told The Times that advertising revenue dropped sharply after the President’s Office allegedly asked companies to boycott the publication.

According to Forbes Ukraine, the outlet lost $240,000 in advertising revenue due to this pressure.

Ukrainska Pravda first reported systematic pressure from the President’s Office in October 2024, just months after investigating corruption cases involving Zelenskyy’s inner circle.

What this reveals

Ukrainska Pravda’s investigation confirms what many suspected: dramatic claims of Russian infiltration provided convenient cover for an attempt to destroy institutional independence. The evidence for that infiltration remains conspicuously absent.

Two NABU detectives remain imprisoned on charges the investigation suggests may lack substance. The episode demonstrated Ukrainian democratic culture’s resilience, but also showed how easily security services can be weaponized when investigations reach the wrong people.

For now, civil society has successfully resisted institutional capture. The protests forced parliament to restore anti-corruption agency independence. International pressure secured Tsyvinskyi’s appointment, demonstrating that merit-based selections can prevail.

But vigilance remains essential. The President’s Office has demonstrated its willingness to take drastic measures to protect Zelenskyy’s inner circle—using fabricated security concerns, weaponizing law enforcement, and pressuring media outlets.

The successful resistance offers hope that Ukraine’s democratic institutions can withstand authoritarian pressure. But it also serves as a warning: when corruption investigations reach the very top, the defenders won’t hesitate to destroy the institutions themselves.