Finding Meaning in Human Lives

AI is replacing humans in the workplace, with tech companies among the quickest to simply innovate people out of the job market altogether. Amazon announced plans to lay off up to 30,000 people. The company hasn’t commented publicly on why, but Amazon’s CEO Andy Jassy has talked about how AI will eventually replace many of his white-collar employees. And it’s likely the money saved will be used to — you guessed it — build out more AI infrastructure.

This is just the beginning. “Innovation related to artificial intelligence could displace 6-7% of the US workforce if AI is widely adopted,” says a recent Goldman Sachs report.

In the last week, over 53,000 people signed a statement calling for “a prohibition on the development of superintelligence.” A wide coalition of notable figures, from Nobel-winning scientists to senior politicians, writers, British royals, and radio shockjocks agreed that AI companies are racing to build superintelligence with little regard for concerns that include “human economic obsolescence and disempowerment.”

The petition against superintelligence development could be the beginning of organized political resistance to AI's unchecked advance. The signatories span continents and ideologies, suggesting a rare consensus emerging around the need for democratic oversight of AI development. The question is: can it organize quickly enough to influence policy before the key decisions are made in Silicon Valley boardrooms and government backrooms?

But it’s not just jobs we could lose. The petition talks about the “losses of freedom, civil liberties, dignity… and even potential human extinction.” It reflects a deeper unease about the quasi-religious zeal of AI evangelists who view superintelligence not as a choice to be democratically decided, but as an inevitable evolution the tech bros alone can shepherd.

Coda explored this messianic ideology at length in "Captured," a six-part investigative series available as a podcast on Audible and as a series of articles on our website, in which we dove deep into the future envisioned by the tech elite for the rest of us.

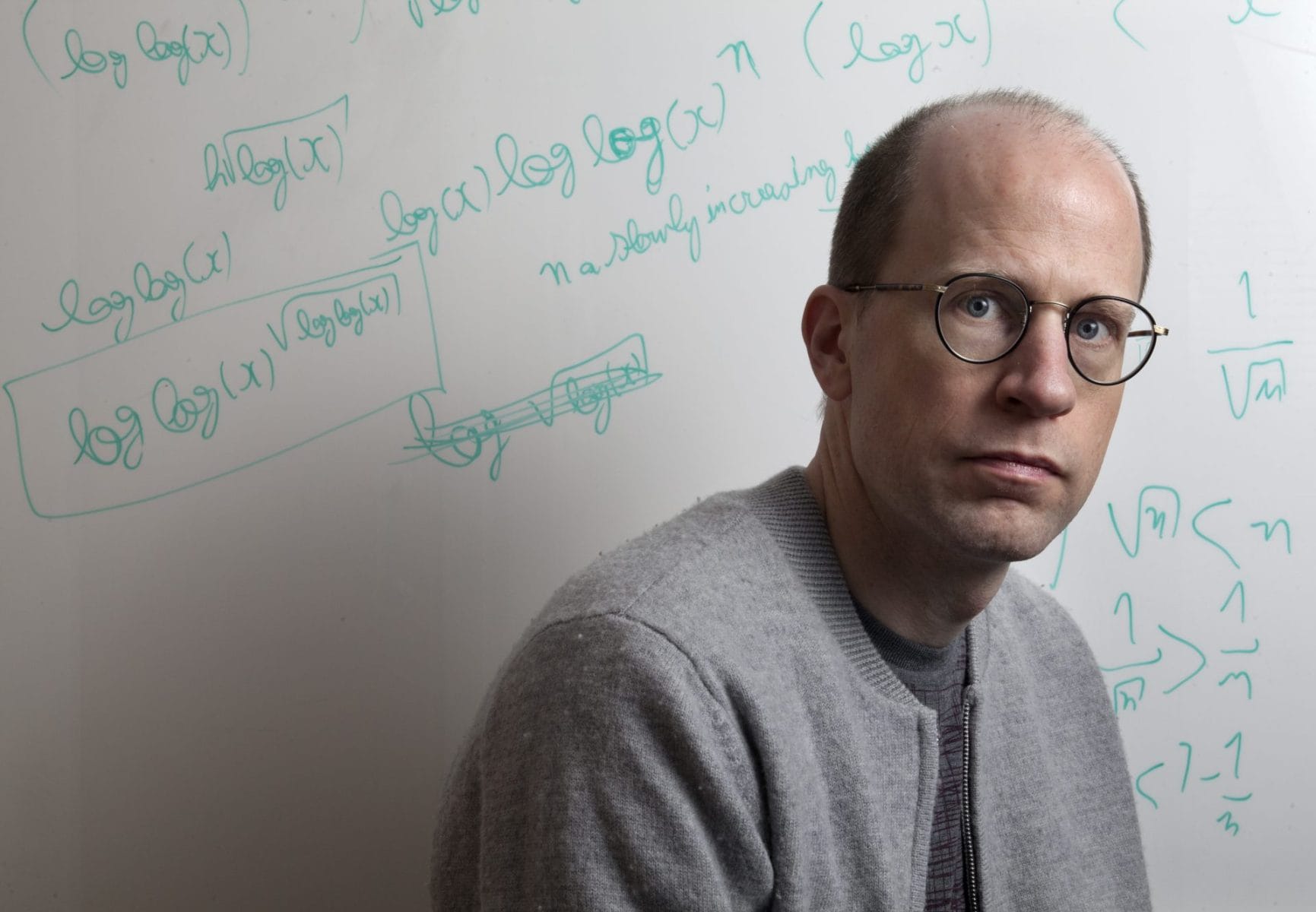

The Washington Post / Contributor via Getty Images

During our reporting, data scientist Christopher Wylie, best known as the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower, and I spoke to the Swedish philosopher Nick Bostrom, whose 2014 book foresaw the possibility that our world might be taken over by an uncontrollable artificial superintelligence.

A decade later, with AI companies racing toward Artificial General Intelligence with minimal oversight, Bostrom’s concerns have become urgent. What struck me most during our conversation was how he believes we’re on the precipice of a huge societal paradigm shift, and that it’s unrealistic to think otherwise. It’s hyperbolic, Bostrom says, to think human civilization will continue to potter along as it is.

Do we believe in Bostrom’s version of the future where society plunges into dystopia or utopia? Or is there a middle way? Judge for yourself whether his warnings still sound theoretical.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Christopher Wylie: To start, could you define what you mean by superintelligence and how it differs from the AI we see today?

Nick Bostrom: Superintelligence is a form of cognitive processing system that not just matches but exceeds human cognitive abilities. If we're talking about general superintelligence, it would exceed our cognitive capacities in all fields — scientific creativity, common sense, general wisdom.

Isobel Cockerell: What kind of future are we looking at — especially if we manage to develop superintelligence?

Bostrom: So I think many people have the view that the most likely scenario is that things more or less continue as they have — maybe a little war here, a cool new gadget there, but basically the human condition continues indefinitely.

But I think that looks pretty implausible. It’s more likely that it will radically change. Either for the much better or for the much worse.

The longer the timeframe we consider — and these days I don’t think in terms of that many years — we are kind of approaching this critical juncture in human affairs, where we will either go extinct or suffer some comparably bad fate, or else be catapulted into some form of utopian condition.

You could think of the human condition as a ball rolling along a thin beam — and it will probably fall off that beam. But it’s hard to predict in which direction.

Wylie: When you think about these two almost opposite outcomes — one where humanity is subsumed by superintelligence, and the other where technology liberates us into a utopia — do humans ultimately become redundant in either case?

Bostrom: In the sense of practical utility, yes — I think we will reach, or at least approximate, a state where human labor is not needed for anything. There’s no practical objective that couldn’t be better achieved by machines, by AIs and robots.

But you have to ask what it’s all for. Possibly we have a role as consumers of all this abundance. It’s like having a big Disneyland — maybe in the future you could automate the whole park so no human employees are needed. But even then, you still need the children to enjoy it.

If we really take seriously this notion that we could develop AI that can do everything we can do, and do it much better, we will then face quite profound questions about the purpose of human life. If there’s nothing we need to do — if we could just press a button and have everything done — what do we do all day long? What gives meaning to our lives?

And so ultimately, I think we need to envisage a future that accommodates humans, animals, and AIs of various different shapes and levels — all living happy lives in harmony.

Cockerell: How far do you trust the people in Silicon Valley to guide us toward a better future?

Bostrom: I mean, there’s a sense in which I don’t really trust anybody. I think we humans are not fully competent here — but we still have to do it as best we can.

If you were a divine creature looking down, it might seem like a comedy: these ape-like humans running around building super-powerful machines they barely understand, occasionally fighting with rocks and stones, then going back to building again. That must be what the human condition looks like from the point of view of some billion-year-old alien civilization.

So that’s kind of where we are.

Ultimately, it’ll be a much bigger conversation about how this technology should be used. If we develop superintelligence, all humans will be exposed to its risks — even if you have nothing to do with AI, even if you’re a farmer somewhere you’ve never heard of, you’ll still be affected. So it seems fair that if things go well, everyone should also share some of the upside.

You don’t want to pre-commit to doing all of this open-source. For example, Meta is pursuing open-source AI — so far, that’s good. But at some point, these models will become capable of lending highly useful assistance in developing weapons of mass destruction.

Now, before releasing their model, they fine-tune it to refuse those requests. But once they open-source it, everyone has access to the model weights. It’s easy to remove that fine-tuning and unlock these latent capabilities.

This works great for normal software and relatively modest AI, but there might be a level where it just democratizes mass destruction.

Wylie : But on the flip side — if you concentrate that power in the hands of a few people authorized to build and use the most powerful AIs, isn’t there also a high risk of abuse? Governments or corporations misusing it against people or other groups?

Bostrom: When we figure out how to make powerful superintelligence, if development is completely open — with many entities, companies, and groups all competing to get there first — then if it turns out it’s actually hard to align them, where you might need a year or two to train, make sure it’s safe, test and double-test before really ramping things up, that just might not be possible in an open competitive scenario.

You might be responsible — one of the lead developers who chooses to do it carefully — but that just means you forfeit the lead to whoever is willing to take more risks. If there are 10 or 20 groups racing in different countries and companies, there will always be someone willing to cut more corners.

Wylie: More broadly, do you have conversations with people in Silicon Valley — Sam Altman, Elon Musk, the leaders of major tech companies — about your concerns, and their role in shaping or preventing some of the long-term risks of AI?

Bostrom: Yeah. I’ve had quite a few conversations. What’s striking, when thinking specifically about AI, is that many of the early people in the frontier labs have, for years, been seriously engaged with questions about what happens when AI succeeds — superintelligence, alignment, and so on.

That’s quite different from the typical tech founder focused on capturing markets and launching products. For historical reasons, many early AI researchers have been thinking ahead about these deeper issues for a long time, even if they reach different conclusions about what to do.

And it’s always possible to imagine a more ideal world, but relatively speaking, I think we’ve been quite lucky so far. The impact of current AI technologies has been mostly positive — search engines, spam filters, and now these large language models that are genuinely useful for answering questions and helping with coding.

I would imagine that the benefits will continue to far outweigh the downsides — at least until the final stage, where it becomes more of an open question whether we end up with a kind of utopia or an existential catastrophe.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Coda Currents newsletter. Sign up here.

Your Early Warning System

This story is part of “Captured”, our special issue in which we ask whether AI, as it becomes integrated into every part of our lives, is now a belief system. Who are the prophets? What are the commandments? Is there an ethical code? How do the AI evangelists imagine the future? And what does that future mean for the rest of us? You can listen to the Captured audio series on Audible now.

Related Articles

Who owns the rights to your brain?

Captured: how Silicon Valley is building a future we never chose

When I’m 125?

The post Finding Meaning in Human Lives appeared first on Coda Story.