Ukraine just stripped the leader of Putin’s favorite church—his 8,000 parishes are next

Metropolitan Onufriy, leader of the Moscow-aligned Ukrainian Orthodox Church (UOC MP), has had his Ukrainian citizenship revoked, the Ukrainian Security Service announced.

The announcement comes amid growing tensions over the UOC MP’s allegiance in a war increasingly recognized to be driven by the quasi-religious ideology of the “Russian world,” promoted by the Moscow Patriarchy, which is still recognized as the mother church by many UOC MP faithful.

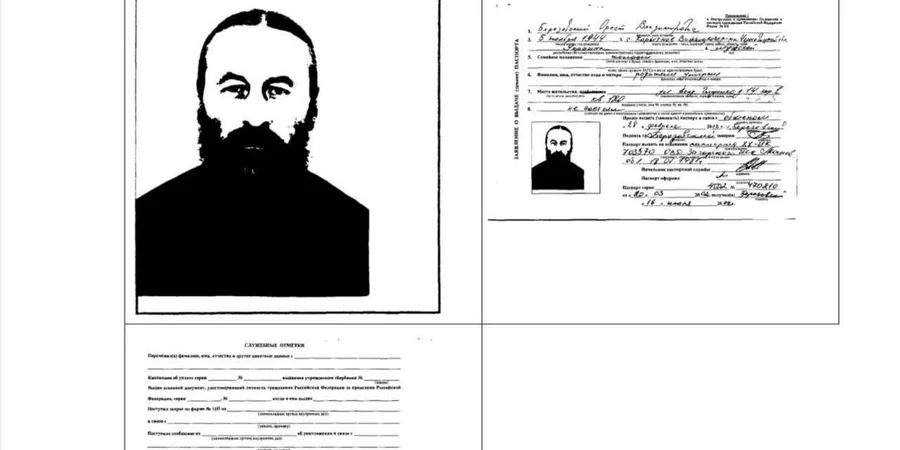

The Security Service (SBU) reported that Onufriy, birthname Orest Berezovskyi, had willingly received Russian citizenship in 2002, while still holding the status of a Ukrainian citizen.

At the time, dual citizenship was prohibited by Ukrainian law, and while a groundbreaking law allowing dual citizenship is pending approval by Ukrainian President Zelenskyy, it still prohibits allegiance to “unfriendly states” like Russia for Ukrainian citizens.

Reportedly, Zelenskyy has signed the decree stripping Onufriy of citizenship, although it has not been published.

UOC MP denies everything, vows to fight back

A UOC MP spokesman rejected the claim that the UOC MP primate has a Russian passport and stated that Onufriy has only Ukrainian citizenship.

Metropolitan Onufriy of the UOC (MP) will also appeal the presidential decree and prove that he has no other citizenships than Ukrainian, the spokesman said in a comment to Suspilne.

The issue of Onufriy’s citizenship had already come up in 2023, when a media report found that he and 20 other UOC MP hierarchs had Russian passports.

After the publication, the UOC MP’s top hierarch decried Russia’s invasion and claimed that his Russian citizenship was extended by default from the time when he lived and studied in Moscow. Nevertheless, now he does not have a Russian passport now and considers himself only a Ukrainian citizen, he said without specifying when he stopped being a Russian citizen.

However, media reports from NV and Agenstvo have circulated scans of Onufriy’s allegedly valid passport, casting doubt on these refutations.

Can Ukraine actually strip its citizens of citizenship?

Ukraine’s Constitution prohibits stripping citizenship—but allows terminating it for those who voluntarily acquired foreign passports without resolving their Ukrainian status.

Parliament member Serhiy Vlasenko explained that Onufriy now automatically becomes a foreigner in Ukraine, losing all citizen rights. He must register as a foreign resident, obtain residence and work permits—”the same procedures as any Russian Federation citizen coming to Ukraine.”

The legal distinction matters. President Zelensky previously terminated citizenship for oligarchs Igor Kolomoisky, Viktor Medvedchuk, and businessman Hennadiy Korban using identical grounds: holding undeclared foreign passports.

Onufriy can challenge the decree in court. But if judges confirm he holds a Russian passport, the presidential decree stands. And renouncing Russian citizenship isn’t simple—it requires a “long, complex, bureaucratized procedure” involving personal participation in Russian consular processes.

The citizenship revocation transforms Ukraine’s top Moscow-aligned cleric into a legal foreigner in the country where he leads 8,000 parishes.

What will happen to Onufriy?

Ukrainian law technically gives stateless individuals three months to leave before facing deportation. But reality operates differently. As Archbishop Iona of the St. Iona Monastery casually noted on Facebook, many UOC bishops stripped of citizenship “continue to live and serve the church and people of Ukraine. Don’t panic.”

Namely, 13 UOC hierarchs lost their citizenship in January 2023. Five more followed in February 2023. None were deported. They remain in Ukraine, conducting services, managing parishes—functionally unchanged despite their legal limbo.

The SBU’s move creates a different kind of pressure. If Onufriy attempts international travel, he faces the fate of businessman Hennadiy Korban and others stripped of Ukrainian passports: denied re-entry, effectively trapped inside the country they call home.

But deportation? Unlikely. Ukraine lacks both political will and practical mechanisms to forcibly remove an 80-year-old religious leader whose 8,000 parishes still serve millions of faithful. The state has bigger battles, like the ongoing court proceedings under August 2024’s law banning Moscow-linked religious organizations.

The nine-month transition period for churches to prove independence has expired. The UOC MP now faces potential dissolution of its entire network—a far more existential threat than one prelate’s passport problems.

The citizenship revocation serves as legal theater while the real drama unfolds in courtrooms where the UOC MP’s survival hangs in the balance.

“Not about banning.” Theologian unpacks Ukraine’s new anti-Russian church law

Is the UOC MP aligned with Moscow?

The status of the UOC MP in Ukraine became especially contentious after Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. The Moscow-aligned church, which enjoyed privileged status for years while promoting “Russian world” ideology, came under increased pressure to clarify its allegiance.

And while the UOC MP claimed to sever ties with its mother church, the Russian Orthodox Church, in May 2022, it did not walk the talk, a Ukrainian expert committee found in 2023.

Reportedly, there is a split within the church, with hardliner parishes ignoring the instructions to no longer pray for the Moscow Patriarch during liturgies.

As well, the alleged severance of ties is not followed up by recognition of the UOC MP as a separate entity in the Orthodox world’s constellation of independent churches. The UOC MP hierarchs are also, apparently, still part of the Moscow Patriarchy’s ruling structure—the Synode.

The Ukrainian state has attempted to curb the UOC MP’s influence—not only via the August 2024 law, but by opening 174 probes into the collaboration of separate church hierarchs with Russia, with 31 guilty sentences.

However, many UOC MP faithful insist they are patriots of Ukraine, with select church voices stressing that UOC MP faithful defend Ukraine in the ranks of the Ukrainian army.

Thus far, the UOC MP’s status is hybrid: while some leaders like Metropolitan Iona have flipped from “Russian world” advocate to self-declared Ukrainian patriot, leaflets promoting Russian chauvinistic and imperialistic views are still observed in other church centers.

Anatomy of treason: how the Ukrainian Orthodox Church sold its soul to the “Russian world”

Growing church drama in Ukraine

The UOC MP’s precarious position is complicated by competition with the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU), granted independence by Moscow Patriarch Kirill’s nemesis, Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, in 2018.

Both structures have roughly similar numbers of parishes (8,097 UOC MP vs 9,000 OCU). 687 parishes have ditched affiliation with the UOC MP to join the OCU since 2022. However, these transitions are increasingly marred by accusations of forceful takeovers amid state backing.

What is Moscow’s stake? The UOC MP represents a whopping 23% of the Russian Orthodox Church’s parishes worldwide, and is the largest concentration of parishes outside Russia itself.

The UOC MP remains Moscow’s sole surviving pillar of influence in a Ukraine that has otherwise severed all connections to Russia since 2022. Its ideological power runs deep: the fantasy of Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus as “Holy Rus” united against the “satanic West” forms the theological cornerstone of Putin’s war.

This, as well, as revocations of leases on historic churches in state property, has prompted the UOC MP to lead a campaign decrying alleged religious persecution in Ukraine. This messaging has had impressive success among American Republicans, largely due to the lobbying efforts of lawyer Robert Amsterdam.

The Ukrainian state would indeed prefer a single Orthodox Church, and public opinion increasingly backs decisive action.

A June 2025 SOCIS poll found 34.7% of Ukrainians support liquidating the UOC MP as a legal organization, while 10.8% favor forcing its merger with the OCU.

Combined, 45.5% want the state to act decisively.

Yet 31.7% believe the government shouldn’t interfere in religious affairs, revealing Ukraine’s deep ambivalence about using state power against a church that still claims millions of faithful.

The resistance of even Ukraine-oriented UOC MP parishes to joining the OCU structure hints at deeper issues beyond historical animosity between two competitors.

Clashing allegiances, models of religious life, and the OCU’s desire to occupy the privileged state-promoted status once held by Moscow’s church in Ukraine will continue to stir Ukraine’s religious life for many years ahead.

Editor’s note: This article was updated to include the section “Can Ukraine actually strip its citizens of citizenship?”