Addressing polarization and hate through social networks

Many people see the roots of polarization and hate in the information ecosystem in which we are embedded. This leads us to conversations about disinformation, platform power, and the politics of speech. I see the roots differently. In my mind, polarization and hate are expressions of a fractured social graph, of people not being connected to one another in meaningful and deep ways. Divisions in social networks (connections between people, not technologies) have serious consequences.

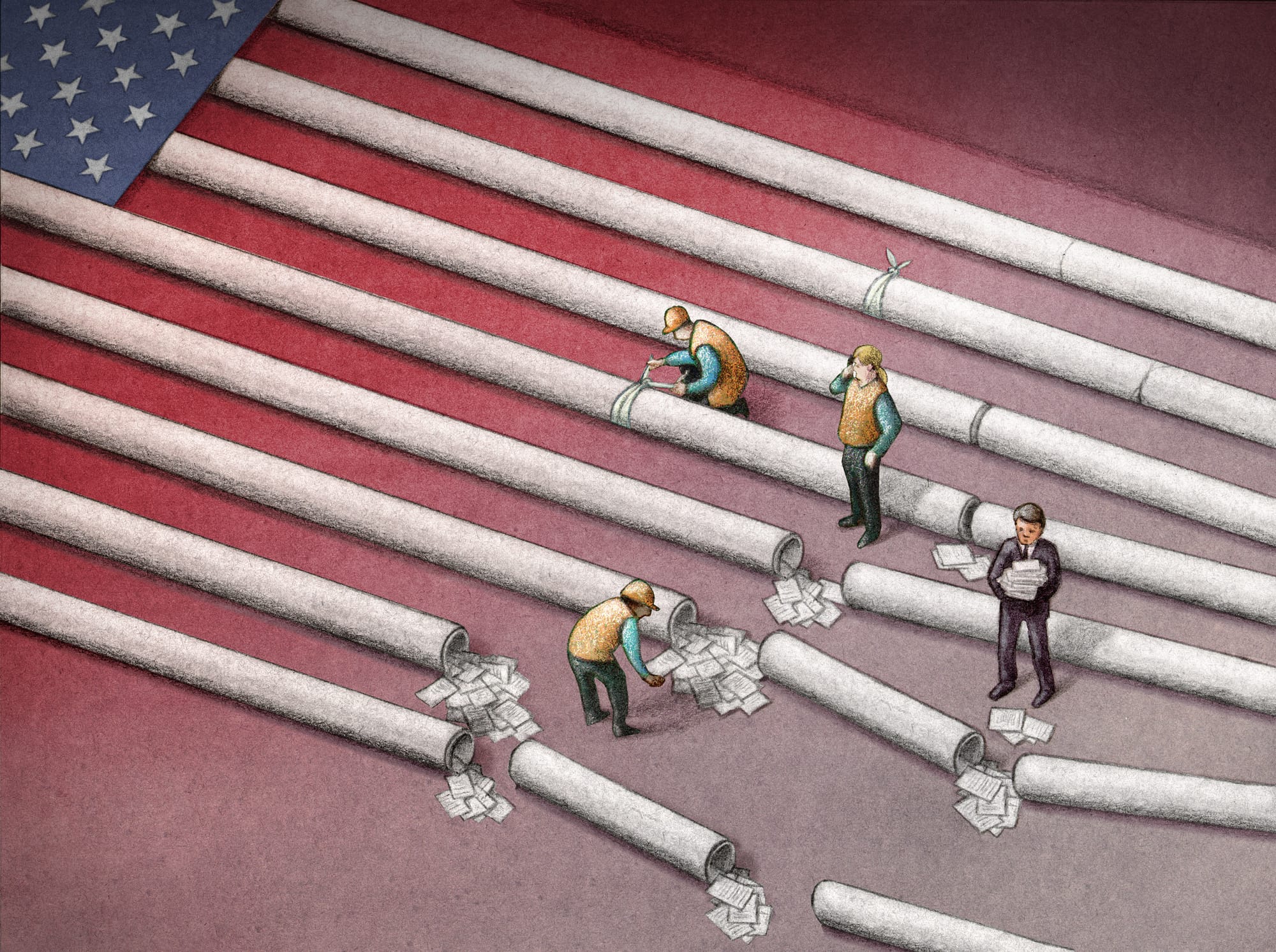

The social graph of society is civic infrastructure, but too few people really understand how this needs to be nurtured and maintained. Plenty of people do this by feel. You can see this in the military and in higher education. You can see this when organizations build mentorship programs and when social workers build plans to help people leave “the life.” But you can also see how people manipulate the social graph in order to aid and abet a range of political, ideological, and economic agendas. There is nothing “neutral” about the social fabric of society. Ignoring it doesn’t mean that it will be healthy, but it does create a vulnerability that can be abused.

On May 18, 2021, I gave a keynote at Educause’s annual conference about what we can and should do to knit a healthy social fabric. The framing of the talk (especially the solutions) is centered in the American education context, but the need for repairwork is articulated more broadly. In short, we cannot sustain democracy or work towards a more equitable society without grappling with the social network of our various countries. There are many things that we can and should be doing in every part of society — including business, government, and civil society — so I hope you’ll read this talk and start imagining interventions that you can do to make the world a healthier place.

The Talk:

I am honored to be speaking here today. Thank you all for the work that you’ve done during this pandemic to keep our schools and students whole. The talk that I am offering today concerns some of my thinking about social networks, the sociological notion of human connections that are the basis of our society’s social fabric.

The concept of a “social network” dates back to the 50s. Scholars who studied the structures of how people related to each other previously discussed the notion of “sociograms.” In the latter half of the 20th century, scores of researchers worked to understand the structures that formed the social fabric of our society, looking both at the micro-level social networks that individual people maintained and the macro-level picture that formed when you saw how those relationships knitted together. New concepts like “the strength of ties” entered the field of sociology to describe the value of connections between people. And it turned out that people could be strategic about developing, maintaining, and strengthening their social networks. For example, as Granovetter argued, weak ties are essential to accessing professional opportunities. Social connections made through school turn out to be a critical foundation for young people’s access to future job opportunities.

Of course, people understood that relationships mattered long before sociologists began conducting social network analysis and labeling social dynamics. And indeed, institutions and politicians have leveraged networks for centuries. Nineteenth century organizational thinking culminated with the concept of “social engineering,” coined in 1899, to describe scientific approaches to managing people. One branch of this helped propel business ideals of efficiency and modernization. Another branch evolved into eugenics. It’s easy to see where some of this thinking went very very very wrong. But there’s too little attention for the places where strategic planning around social networks ended up benefiting society in unexpected ways.

Consider what happened first during World War I and then, more notably, during World War II. If you’re a history teacher, you probably teach your students that Reconstruction after the Civil War ended with the Compromise of 1877. This might have achieved a political closure, but it did nothing to address distrust between the North and the South, let alone the hatred stemming from white supremacy. Hatred and animosity grew during the almost 40 years between that Compromise and World War I. We usually discuss this period through the creation of Jim Crow laws, but North-South hatred among whites grew too. Yet a funny thing happened during the Great European wars. White men from across the country were put together in the same military units. Black men who served were treated as second-class citizens and segregated from white soldiers, but they too served alongside other Black men from across the country. And in WWII, there were a range of situations in which white and Black soldiers fought alongside one another.

After both wars, soldiers returned home. But they went home knowing someone from somewhere else in the country, having built social ties that allowed them to appreciate and humanize people who were different than them. Many of these ties would be activated by former soldiers in the 1950s as the Civil Rights Movement started to emerge. It turns out that the intensity of serving alongside people during a war builds friendships and respect that can knit the country in profound ways. I often wonder what would’ve happen if we hadn’t segregated soldiers during those wars. What if the man who assassinated Medgar Evers had served in the same unit with him? Would he still have become a radicalized Klansman after the war?

Many institutions knit together networks of people, intentionally or not. Communities are formed around faith-based activities, both locally and through service that connects people across geography. Professional bonds are produced within companies and across them. And then, of course, there’s school. And that’s what we’re here to talk about today, school. Because school is a critical site of building social connections. And my talk today is intended to help you think about the role you’re playing in building the social fabric of the future. My ask of you is to take that role seriously, to recognize it, and to be strategic about it. Because you are playing that role, whether you realize it or not.

— -

We often treat the relationships that happen between schoolmates as a wonderful byproduct of education, something that happens but not something that we think about as central to the educational mandate. Sure, we create project teams in the classroom and help form student groups or sports teams with varying degrees of consideration for those groups, but we don’t engineer those teams. Our decision to ignore how peer groups are formed is particularly odd given that we tell ourselves that the reason we have public education is to socialize young people into public life so that we can have a functioning democracy. Many educational communities are deeply committed to addressing inequality and see diversity of schools as key to that mission. But without understanding how to build a social fabric, schools can help hate rise without even trying. By ignoring the work of building healthy networks, by pretending that a neutral role is even possible, we put our social fabric at risk.

During the early years of my studies into young people and social media, I did a mini-project that I never published. I was spending my days in a handful of racially diverse schools in Los Angeles. I noticed that, when the bell rang, those diverse classrooms devolved into racially segregated groupings in the hallways, lunchroom, and courtyards. I decided to examine the social networks that those students performed through social media, pulling down the complete networks at the schools as they were articulated through friend connections. These school has no dominant racial group. But on social media, what I saw was severe racial polarization among peer groups. In short, students might have sat next to people of different races in their classes, but who they talked with in the courtyard and online was racially segregated.

We’ve always known that integration doesn’t just happen. The work of school integration didn’t end with Brown vs. Board. Just because students with different life experiences are in the physical school together doesn’t mean that schools are doing the work to help build ties between people of different life experiences.

People self-segregate for healthy and problematic reasons. Take a moment to think of your own friendships from school. You probably met people who were different than you, but if you’re like most people, your closest connections are still probably from the same racial, socioeconomic, or religious background as you. People self-segregate based on experience, background, and interests. For example, if you were really into basketball, you might have developed friendships with others who share that interest. Taken to the next level, if you were on the basketball team and spending all of your afterschool time doing basketball, your friends are almost certainly dominated by those who were also on the basketball team.

But beyond interests, we look for people who are like us because this is easier, more comfortable. Sociologists call this “homophily” — birds of a feather stick together. But there are choices that we make in an education context that increase or decrease the diversity of people’s social networks. And those choices have lifelong and societal consequences. Those choices happen whether we intend for them to or not.

Consider assigned group project teams with group grades. If you assign people to work together who are similar to each other, they will have a higher likelihood of bonding. That will increase homophily, but it will also increase the perception that those traits are “good.” But if you assign people to work together who are not like one another in order to increase diversity, bonding is not a given. Moreover, if not handled well, this can backfire. Working with people who are different than you is hard. It takes work. It’s exhausting. When we can’t find common ground and a shared goal, we grow to resent those other people who we believe we are “stuck” with. Think about that feeling you’ve had about a group project where someone didn’t pull their weight. The problem is that when we resent an individual who is different than us for a perceived injustice like not pulling their weight, we start to resent the class of people that this person represents to us. In other words, we can increase intolerance through our poorly designed efforts to build diverse teams. Group design matters. Just like pedagogy matters.

If our goal is to diversify the social graph, to help people bridge differences, the structure of the activities must be strategically aligned with that goal. If everyone shares the same goal, they can bond without much more than co-presence. That’s the beauty of a school club or sports team. Having a shared enemy is also helpful, as is the case in sports where the “enemy” is the other team. But the goal of a school project group is articulated by the teacher, not by the students. The students have different goals when they participate. At best, bonding on a group team will happen through shared resentment towards the teacher.

Side note: Many of you are old enough to remember “The Breakfast Club,” where a group of students from different school cliques became friends because of detention. Do you remember how this happened? Shared hatred for the detention monitor mixed with a situation in which students started to be vulnerable with one another.

Bonding happens when there is an intrinsic alignment on goals or an extrinsic enemy. But there’s a third component… When people are vulnerable with each other, those bonds grow more significant. This is true in the military, where you have to be prepared to lay down your life for someone. But this is also true in the dorming at elite American high school and colleges.

People who come out of American elite schooling are often extraordinarily successful, even compared to those educated in elite institutions in other countries. American exceptionalism is often used to justify this sentiment. But let’s be clear — our students are not inherently better, nor are our teachers. I’m a professor. We’re not trained to teach and most of us suck at it. Also, we’ve come to the elite institutions to do research and have no incentive to invest in becoming better teachers. There are exceptional professors out there, but most of them are not at the most elite schools. What makes elite schools elite is rooted in how social networks are formed through universities. And American elite institutions have something that few other universities around the world have: mandatory dorming for multiple years, with rooming assignments assigned by an administrator.

Let’s think about the role of mandatory dorming for a second. If you’re as old as I am, you might remember sending in a form indicating whether you smoke or not and then showing up freshman year to a tiny square cell that you’re sharing with a total stranger. Maybe you wrote that person a letter once over the summer to figure out who was going to bring what. Whether you went to a school that social engineered those roommate pairings or one that randomly generated them, you were forced into a social experiment. You needed to find a way to live with a stranger, which required negotiating intimacy and vulnerability in profound ways. No one told you that this living arrangement was essential to building the social fabric of American society, but it was. Even if you came out of college never speaking to your freshman roommate ever again, you learned something about people and connections through negotiating that relationship. This is how elite networks are made. Being a part of those elite networks is the true value of an elite education.

Of course, even on college campuses, this has changed recently. When Facebook first started popping up on college campuses, I noticed something strange among students. They were using Facebook to self-segregate even before their freshman year began. They begged administrators to change their roommate assignments; they didn’t bond as much with their dormmates when it was hard. Then, when cell phones became an appendage for teens, students in college were opting to maintain ties with their high school friends rather than embark on the discomforting work of building new friendships in college. This year, during the pandemic, freshman in college barely bonded with each other. I realized with horror that these technologies were undermining a social engineering project that students and universities didn’t even know existed. That schools didn’t recognize as valuable. That we’re now starting to pay a price for.

For the last year, as students have negotiated K-12 and college during a pandemic, the lack of awareness about the importance of social tie development became even more profound. We’ve seen countless tools built to help students obtain the school material. Teachers invested in finding ways to transfer classroom pedagogy to the internet, to produce more interactive and compelling video content, often using tools like polls to interact with students. But the primary relationship that was considered was one rooted in a notable power differential — the dynamic between the teacher and the student. Yes, students have still been required to negotiate group projects on Zoom, but how many tools have been rolled out this year that are really about strengthening ties between students? Helping students connect with others in a healthy way? Most of what I’ve seen has focused on increasing competition and guilt. Tools that are designed so that everyone can see each other’s assignments, complete with timestamps that reveal the complex lives students face navigating virtual school. Tools that privilege those who can perform. And tools that are rooted in accounting and accountability. Why are we not seeing tools to help students bond across difference?

— -

Traumatic situations like a pandemic often create ruptures that rearrange social relations. But forced rearrangements of social networks can also be implemented in order to exact trauma for social control. During slavery, abusers lorded power over those they enslaved by controlling their social networks. They broke up families, dictated who could work with one another, “elevated” some slaves over others, and bought and sold people to shape the social networks of Black people in this country. This was also what the Nazi regime did to control the Jewish population in Europe. In both contexts, one of the most radical and important forms of resistance by those enslaved and abused was to build and maintain networks in the shadows. Those networks made the escape of people, ideas, and knowledge possible and produced forms of solidarity that enabled the fight for dignity. This did not end white supremacy, but it allowed life to unfold within it.

The elite world of finance and management consulting offers a different kind of case. Control through indoctrination rather than physical might. When new graduates head off into these worlds, they encounter sector-controlled hazing, not unlike basic training in the military. They must work long hours, and are expected to be on call, to travel, to be responsive to their bosses. This treatment helps dismantle their social networks to outside communities so that their entire network is self-contained. Unlike those who lack free will, these workers are socialized into the idea that their torment is for their greater good and will give them the professional skills and power that they seek. Like the voluntary military, this approach allows for total ideological control. Brain washing. What’s interesting about this dynamic is that most of these workers only spend a few years in these settings, but when they leave them, they operate like a cult member, indoctrinating everyone else into the logics of capitalism at the root of these sectors.

Both of these examples highlight how social networks have been strategically broken and remade for someone else’s agenda. Ironically, compulsory high school was adopted in the United States to also break social networks. While moral reformers had long advocated for compulsory high school in order to protect the morals of young people, it wasn’t until the Depression that the movement took off. The reason was simple. There were too many teenagers taking up too many adult male jobs at a time when there were too few jobs to go around. The fix would seem simple: in effect, jail teenagers by requiring them to be in school. But there’s a fascinating extra twist to this dynamic that few people notice. Until the creation of compulsory high school, sports league were mixed age, including both teenagers and adults. Through sport, teenagers got to know adults who helped get them access to work. By creating high school sports, age segregation was enacted, which appeased the labor unions. Age segregation has had significant costs. When young people do not interact with people of different ages, status and power dynamics turn inwards. This is the root of American school popularity dynamics and many dimensions of our struggle with bullying. Age segregation was a socially constructed project that is now at the root of many of our social ills, a conversation we can dive into in the Q&A.

These three examples highlight large scale efforts to restructure networks in ways that have significant negative consequences, but I also want to highlight smaller interventions that can be quite healthy. If you are a social worker trying to help someone escape a life shaped by addiction, gangs, hate groups, or sex work, you know that a crucial step is to break their social network and help them form new connections. After all, what is at the root of a 12-step program? It’s rooted in building a relationship to God and, in the process, to connect to new people through regular meetings and a community dedicated to a shared desire to escape various versions of “the life.” But the key for such interventions to work is that the person wants help in breaking those ties. Forcing someone to break ties just because you think it’s good for them tends to backfire. You can see this in your schools in the fall-out from forcible foster care programs or when you try to separate kids who are locked into a bad cycle.

Remaking networks is a project that unfolds time and time again. Breaking social relations is life-altering. It can help people respond to trauma, but it is also traumatic. For many people, it means leaving behind friends and family. In “Learning to Labor”, Paul Willis examined why working class youth who are given tremendous educational interventions do not pursue economic opportunities, preferring instead to take on working class jobs. They don’t want to leave behind family and friends. They don’t want to have their social networks broken. Those who do leave are often those who were struggling in their home community. Like LGBTQ youth who escape homophobia and face high rates of both upwards and downward mobility as a result.

All around us, there are interventions designed to affect social network ties in costly ways, often without acknowledging what’s going on. We’re going to talk about ways that you can involve yourself in that dynamic in a bit, where you can help nurture and knit healthy networks. But first, I need to take you on a detour so that you can understand that why the interventions I’m going to ask you to make are radical. And why you will face significant headwinds if you embark on such a journey.

….

When I was growing up as a queer kid in rural Pennsylvania, I spent hours in chatrooms and on forums talking to people who helped guide and support me in making sense of who I am. This is precisely the saving grace that I mentioned earlier, where finding people who could support me helped me feel less alone as I worked through my identity. To my horror, when I returned to those same online fora in the early 2000s, I realized that the young queer people who were crying out for help online were being told that they were immoral and pushed into conversion therapy by missionaries propagating religious indoctrination. At one point, in a panic, I tracked down dozens of obituaries of teens who had died by suicide in the months after the “It Gets Better” campaign went public. As I scoured through them, identifying queer kids who died by suicide and then tracking down their online accounts, I found a sickening pattern. Over and over again, I found queer kids who had come out online and made an “It Gets Better” video in the hopes of finding love and support, community and new connections. Instead, they were harassed cruelly online and, most likely, in school.

Young people who have limited supportive social networks in schools regularly turn to the internet to find support, validation, and encouragement. When I was a teen, that’s exactly what I found. But by the time I was doing research with young people in the 2000s, the stranger danger rhetoric of the 90s had reshaped parents’ perception of the internet. I wrote a whole book about the myths that emerged. What continues to bother me is that parents and educators focus on either abstinence or protective bubbles as the solutions. We’ve been paying the cost of age segregation without realizing it, but we keep doubling down on it. In 1964, activist Jack Weinberg famously said “Never trust anyone over 30.” Without realizing it, he was revealing the costs of a generation of age segregation. The very same age segregation that was manufactured in order to benefit Labor decades before. There is no reason to trust a population if you don’t know that population. We’ve never gotten beyond that dynamic. Each successive age-segregated population in the United States distrusts its elders. This isn’t “natural.” This is socially constructed. And it makes young people vulnerable to strategically placed ideological frames.

For the last few years, I’ve been trying to get my head around why some young people embrace conspiracies and hateful agendas. Time and time again, what I find is young people who are looking for community. Just as queer kids thought they’d find community through making an “It Gets Better” video, I kept finding youth who thought they’d find community by making a swastika laden meme. In the early days of 4chan, this felt like my experience with Usenet back in the day. But in the last few years, I saw a shift that resembles what happened when homophobic adults started targeting queer youth in the early aughts. These days, there’s a lot of money, power, and energy devoted to shaping the worldview of young people, people who are nurturing networks of hate.

Those who are nurturing hate are also purposefully constructing their work in opposition to education. Public education has been controversial in this country throughout its history. We’ve seen a century of battles over funding and vicious debates over what children should learn. Since 1925, with the Scopes Trial concerning the teaching of evolution, we’ve watched parents and other adults challenge what children are taught. We’ve seen countless legal and cultural wars shaping school policy. But this has always been about adult disagreements. That’s been changing in recent years. Today, students are being enrolled in cultural fights to discipline educators. They are now encouraged to record teachers and professors to aid in public shaming. This dynamic runs the political spectrum, but in far-right circles, it is coupled with content designed to destabilize knowledge and fundamentally challenge the project of education.

Consider PragerU, a website filled with slickly produced videos, positioned as educational content and targeting young people. At a surface level, PragerU videos appear to provide a conservative perspective on a variety of contemporary issues. Yet, their motto was “Give us five minutes and we’ll give you a semester” because their creators see their agenda as undoing what they believe is the ideological indoctrination of the American education system. Critics of PragerU videos often call them disinformation, but this isn’t quite right. Yes, parts of what you will find in these videos is misleading, but it’s really the spin and structural positioning that’s so caustic. For example, they have a video set called “What’s Wrong with Feminism” that is designed to reframe history, destabilize data, and seed doubt in values of equity while arguing that gun rights are women’s rights, women aren’t actually raped in college, and there’s no wage gap. This content also sets in motion frames that are deployed in denying the transgender experience, aiming to reclaim clear divisions between men and women, and arguing that there’s a war on boys.

The content here has a lot in common with the controversial 1994 book “The Bell Curve.” At first blush, that toxic book appeared to provide scientific evidence of race-based differences. But the choices around data and analysis, including the purposeful avoidance of societal factors like discrimination that led to statistical differences, resulted in a book that was eugenics-style hate cloaked as modern science. Just as scientific racism in texts like “The Bell Curve” was used to perpetuate inequality, PragerU’s style of anti-feminism is designed to enable the oppression of gender non-conforming people as well as men and women who do not want to conform to conservative ideas of sex roles.

But PragerU’s videos don’t stand alone as content to be consumed or ignored. It’s situated within a networked ecosystem designed to fuel grievance culture, break social ties and rebuild them. Not only do these videos reinforce differences between people, but they also serve to justify anger towards anyone who is pushing for a more-just society. They destabilize knowledge intentionally so that others can remake it in their image. Disinformation campaigns are fundamentally projects to restructure social networks. They begin with breaking the frames you already have and then telling you that the people teaching you this are either duped or malignant. In other words, you’re forced to go to school to learn from teachers whose job is to indoctrinate you into radical left fantasies. Once that frame is in place, other frames can emerge. Once you start down a path of destabilized knowledge that blames feminists, you’ll be introduced to other frames that tell you that the “real problem: is immigrants, Black people, Jews, and Muslims. Those who go down this rabbit hole are encouraged to “self-investigate”, while selective facts and spun content are pumped out to be found. They are bound to stumble on slickly produced, SEO-maximized content like PragerU which is designed to “prove” that you are a pawn in a leftist agenda. Due to how information is arranged and made available on the internet, it’s a lot easier to access a toxic YouTube conspiracy video from someone who says they are an expert than to access scientific knowledge or news content, which is often locked behind a paywall.

Students who struggle to form bonds at school turn to the internet to find community. Students whose parents teach them not to trust teachers look for alternative frames. Students who are struggling in the classroom look for alternative mechanisms of validation. All of these students are vulnerable to frames that say that the problem isn’t them, but something else. And when they turn to the internet to make sense of the world, they aren’t just exposed to toxic content. Their social networks also change. Epistemology — or our ability to produce knowledge — has become weaponized as a tool to remake social networks. Political polarization is not just ideological; it’s also written into the social graph itself.

In the 1990s, a group of scholars were deeply concerned about how scientific knowledge was under attack. They were watching journalists engage in false equivalence as they amplified purportedly scientific arguments designed to destabilize consensus about climate change. They were watching politicians spin new narratives designed to seed doubt. Recognizing that epistemology is the study of knowledge, they coined a term to describe the study of ignorance: “agnotology.” In the scientific community, ignorance is often assumed as “not yet knowing.” But these scholars recognized two other types of ignorance: 1) knowledge that has been lost; and 2) knowledge that has been destabilized and polluted. The former concerns the kinds of knowledge that are lost due to genocide or the erasure of a language, but also the kinds of knowledge that disappear when that one person in an organization who knew how X works leaves the organization. The latter concerns what happens when adversarial actors try to undermine knowledge for political, economic, or ideological gains. Agnotology provides a fantastic framework for understanding disinformation. But what’s notable about the manufacturing of ignorance is that it’s not possible without grappling with social networks.

In short, to radically alter how people see the world, you have to alter their connections to those who might challenge these new frames. And that’s what we’re now seeing. Because education in the United States is designed to help uphold certain ideals of democracy and because schools have increasingly moved towards embracing diversity, resisting white supremacy, and inviting people to critically examine the arrangements of power, you are a threat. But it is not just what you teach that is threatening. It’s how schools build social relationships among peers that is threatening. Whether you realize it or not, all of you — as educators, librarians, and tool builders — are configuring public life in ways that threaten a range of financial, ideological, and political goals. Just by trying to teach students. Just by creating the conditions through which students meet. Even when you’re trying not to remake the social fabric.

At some level, this shouldn’t be surprising. After all, there’s a lineage of the homeschool movement that was born out of fear that secular education would prompt young people to question God and meet secular people who didn’t believe in God. But you’re now threatening more than the church. Earlier fights centered on funding, part of a broader austerity logic framed as being about efficiency. But I want to warn you, this new fight will center on rearranging the social networks of your students and reconfiguring how they see the world in ways that will make the classroom far more contentious.

….

The making and remaking of networks for ideological, economic, and political purposes is all around us. Many educators would prefer not to engage in a project of nurturing and nudging social networks. It feels weird. We want to be neutral. And yet, because it is happening all around us, we are also bearing witness to the social costs of not being aware of network-making. Most educators and tool builders don’t consider how their practices shape social networks. And most students don’t recognize how networks also shape their worlds.

I firmly believe that it’s high time that we recognize that education shapes the social graph and make a concerted effort to grapple with that in our classrooms and in our tool building. Simply put, we cannot have a democracy if we aren’t thoughtful about our social fabric; we will fall into civil war. Moreover, we cannot address inequality or increase diversity without being conscientious nurturers of the social graph. Many of the challenges we’re facing today — polarization, hate, violence, and anomie — can be addressed by actively, intentionally, and strategically nurturing the social graph of our society. Once you start seeing how networks are formed and reformed, I’m confident you will be able to come up with a range of interventions that go beyond what I might suggest. But I want to give you some concrete examples of interventions that have or could make a difference by focusing on different levels of the puzzle.

First, let’s flip the stranger danger rhetoric on its head and think about places where strangers can be an asset. When young people are crying out for help on the internet, who should they find? Because of stranger danger rhetoric, most people look away when they encounter a TikTok video of someone in pain. In our classrooms, we teach young people how to be active as bystanders when they witness meanness in school, but every day, we adults ignore the pain that we see on the internet. Why? This is just one way in which our commitment to stranger danger perpetuates harm through inaction. But let me offer three ways to flip that script:

1. I’m on the board of an organization called Crisis Text Line. If you send a text to 741741 when you’re in a crisis, a trained counselor — a stranger — will respond and strategize with you to help you get the help you need. We have managed millions of conversations. A large swath of the outreach comes from students. The reason that we’re trying to get our service integrated into a range of platforms is so that young people turn to trained counselors rather than ending up encountering ill-intended strangers. This is important because there are so few well-intended strangers operating as responsible bystanders on the internet. Some schools have even started to put our phone number on the back of school ID cards to help ensure that students reach out to people trained to help. This is but one example of a way in which we can strategically point young people to strangers who will help them rather than telling them that all strangers are bad. Cuz the more that we drumbeat stranger danger, the more that all interactions with strangers will be negative for the simple reason that responsible strangers will refuse to engage with people who are crying out for help.

2. For decades, volunteers have participated in street outreach programs to help those people experiencing homeless get access to resources. There are countless needle exchange programs to compassionately help those suffering from addiction. Yet, we have no such street outreach programs for the internet. Imagine, if you will, digital street outreach programs designed to reach out to those in pain online. Perhaps the goal is to connect people to resources, but the much simpler goal of human acknowledgement can go a long way. After all, if the only people showing compassion to those who are in pain are those with a nefarious agenda, we’ve got a problem. A big problem. As educators, you can encourage your students to do digital street outreach, to learn to “see” people in pain. This is social-emotional learning in action. Start by teaching your students to see. And then invite them to reach out and offer resources where they can go for help. Empathy is everything.

3. Penpal programs have long been used to bridge societal disconnects. They were popular during the Cold War era to bridge gaps as we were on the edge of a nuclear crisis. But these programs have mostly faded because of a combination of technology and fear of strangers. This doesn’t need to be the case. Technology can be leveraged to strategically and safely connect young people as penpals. Heck in a pandemic world, the number of distinct schools using the same platforms was profound; why weren’t students being connected to support each other? Tool builders and educators: you could work together to build connections not simply between schools, but in a strategic way that knits the public together. You could start with students, but some of the strongest knitting you could help with are across generations. Earlier programs existed to connect prisoners to students. There also used to be more connections between students and elderly communities, but those too have faded. In learning more about the disappearance of these programs, I consistently found that no one understood the value of them; stranger danger befell most of them. But I’m hoping that, from today’s talk, you can see the reason that such programs are important. Perhaps you can think of other connections that can strategically be made. In 2017, I encouraged a group of students to start writing letters to civil servants in the federal government who felt downtrodden and miserable. I can’t tell you how much that made their day. What would it mean to connect students and civil servants as part of history, science, or civics? Certainly, at the collegiate level, there are good hooks to connect practitioners and students. Together, educators and tool builders could build programs that systematically connected people, rooted in an understanding of why this mattered.

Let’s now ratchet up a level. Penpal programs focus on individual connections at scale to build a social graph of connection. But thanks to technology, we can get a lot more strategic in our thinking of the graph as a whole. Many of you in this room are not just educators. You build tools. And you leverage tools in a range of educational contexts. And this is where we start ratcheting up to consider the organizational possibilities. Let’s envision something that you could do at the school level.

Have you ever mapped the social graph of your school? Which students were in class together through their history as students? Who are friends with one another? Who have common interests or are part of the same teams? Most likely, you have a range of accounting tools at your school that helps you track individual students and their performance. But what about the health of the social graph? If you put the social network at the center of your work, how might that change some of your practices? As an administrator, you could assign classrooms strategically. As a teacher, this could shape how you constructed group projects, how you seated students. You do much of this by feel already, but a tool lets you shift your goals. Rather than making your goal be about the success of the group project, imagine a goal that’s about strengthening the graph of the students.

In terms of building connections, one powerful way is to change the context. This is why new friendship form every fall at the beginning of school, when students are exposed to new people through a change in ritual. But you can also do this through strategic disruptions. Many schools host fieldtrips. Independent schools and colleges often take this to the next level when they send small groups of students together on trips where they might do a volunteer project or learn something specific. These are powerful opportunities for creating connections. So how are those trip teams constructed? You can strategically create the conditions by how you choose who to put together.

Stanley Milgram was a psychologist best known for his “obedience to authority” experiments, but he also conducted a series of studies of “familiar strangers.” Consider someone you see ritualistically but never really talk with. The commuter who is on your train every day, for example. If you run into that person in a different context, you are more likely to say hello and strike up a conversation. If you are really far from your comfort zone, you almost certainly will bond at least for a moment. Many students are familiar strangers to one another. If you take them out of their context and place them into an entirely different one, they are more likely to bond. They are even more likely to bond when the encounters keep happening.

Many people have long wondered why the Grateful Dead succeeded in creating a world of Deadheads. It turns out that’s because the people who allocated tickets understood familiar strangers. If you bought a ticket for a Grateful Dead show in Miami, they kept a record of who you were seated near. Then, if you bought a ticket for the Nashville show, they’d seat you near someone who was near you in Miami. By the time you encountered the same people in your section of the show in Chicago, you’d be talking to them.

You can strategically nudge people to connect by creating the conditions where they keep encountering each other. Even if the relationship does not persist when they return to their normal context, they’ll have a mutual sense of appreciation for one another. This is the power of taking networks seriously. And because of technology, you can see how things evolve over time. These are but a few potential ideas for how you as educators and tool makers can contribute to the intentional nurturing of the social fabric. But what I want you to see is that this is doable. You can be as intentional about knitting the social graph as you are about your pedagogy. And both are key to empowering your students.

Currently, you nudge all the time without realizing it. But let me be clear — you don’t have to do this without your students knowing that this is what’s happening. Now that you understand that this is happening, you can make it a conscientious part of your own practice. And you can teach your students how to see networks and understand networks. You encourage students to make new connections for future job opportunities, but you can also invite them to really evaluate their network and think about how to be more reflexive about what relationships they are nurturing. You can work with students to creatively think about how to build connections for the health of the broader social fabric. After all, most students aren’t looking to undermine democracy. They don’t want to be a pawn in someone else’s plan. So empower them to be strategic in the network-making project.

…

Our civic infrastructure and social contract are crumbling. We all know that education has a crucial role to play in a healthy democracy. Yet, what I want you to take away from my talk today is that building and knitting the social fabric connecting your students is as important as the material you teach. You have the power to construct social networks in a healthy way. And those of you who build tools have the ability to enable such connections through your design decisions. Ignoring this won’t make it go away, but it may help our country fall apart. My ask of you today is to take this need seriously and strategize ways to knit the social fabric collaboratively.

Thank you!

Note: This is a modified version of the script I used to prepare my talk, edited slightly based on feedback and the Q&A to clarify points that weren’t as strong as I would’ve liked. I can’t promise these were the exact words that came out of my mouth.