The West is losing the information war because it won’t fight dirty

You show Russians footage of their soldiers dying in Ukraine. They get angry—and mobilize to avenge them. You appeal to their humanity with pictures of Ukrainian children killed by Russian bombs. They shrug. You try facts about war crimes. Nothing.

But tell them criminals are being released from prison to join the army? That their sons might get raped by fellow soldiers? That crime is soaring back home while they’re dying in Ukraine?

Now you’ve got their attention.

This counterintuitive discovery comes from Ukrainian psychological operations teams who’ve spent three years learning what British propagandist Sefton Delmer figured out fighting the Nazis: facts don’t defeat propaganda. Self-interest does.

“People see the corpses of dead Russians and they’re like, well, I’m going to go and defend them,” Peter Pomerantsev tells me, describing Ukrainian research into failed propaganda attempts.

The author of “How to Win an Information War” has spent years studying both Soviet disinformation and Western attempts to counter it. His latest book, just translated into Ukrainian, resurrects Sefton Delmer, a forgotten genius who ran Britain’s “black propaganda” operations against Nazi Germany.

What Delmer understood—and what Ukraine is rediscovering—is that authoritarian propaganda doesn’t work through logic. It works through permission.

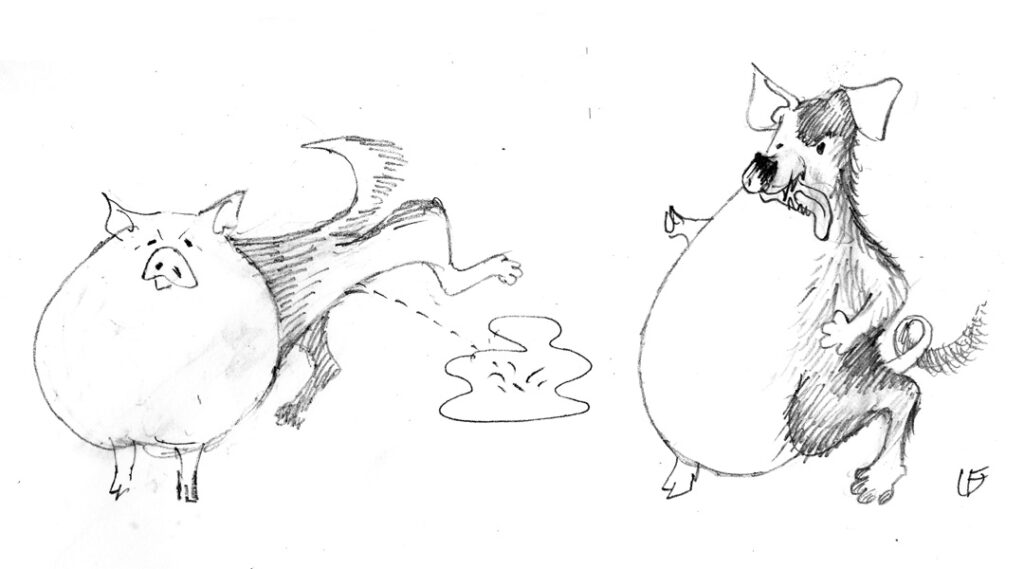

The inner pig dog strategy

Delmer called it appealing to the “inner pig dog”—that part of human nature that’s selfish, greedy, and looking for an excuse to save its own skin.

While the BBC broadcast noble appeals to German democracy, Delmer’s radio stations told Germans it was fine to be corrupt because their officers were stealing everything anyway. Why die for these scum?

“He’d never say that, though,” Pomerantsev explains.

Delmer’s programs featured soldiers raging about corruption, giving lurid details about what Nazi officials were eating while troops starved.

The message was indirect but clear: everyone’s looking out for themselves. You should, too.

One of Delmer’s most successful creations was “Der Chef,” a fake German radio station that posed as an underground voice of disgusted German soldiers. Der Chef would rail against SS corruption with stories so scandalous they became irresistible. When the Nazis converted the monastery of Münsterschwarzach into a military hospital, Der Chef spun a lurid fantasy:

“Two hundred SS men marched into the monastery… A bawdy house was made out of the monastery for the SS men and their whores. The holy mass gowns are used as sheets, and the women wear precious lace tunics made out of choir robes with nothing underneath them… Like this, they go into the chapel and drink liquor out of the holy vessels…”

Der Chef was outraged at such blasphemy—but always returned to these topics, the way tabloids show disgust at depravity while giving readers an excuse to enjoy it.

The approach worked perfectly: breaking taboos against insulting the SS while deepening rifts between party and army, party and people.

But Delmer’s genius wasn’t just in the sensational content.

His operations provided genuinely useful information to Germans—warnings about which districts would be bombed, updates on cities that had been struck, so soldiers could take guaranteed leave to help their families.

The stations posed as German broadcasts, so listeners wouldn’t get in trouble if overhead. They treated Germans as human beings, even while subverting them.

“His radio shows were full of pornography, aggression, a lot of color. It was definitely more than the BBC. It was very tabloid and really rather remarkable,” Pomerantsev explains.

But Delmer’s method was always indirect: “He tells stories about people deserting and we’ll always be like, how horrendous, these traitors are deserting, and give details how they desert with the intention of making people want to desert.”

The parallels to Russia today are striking. Ukrainian research has found similar patterns:

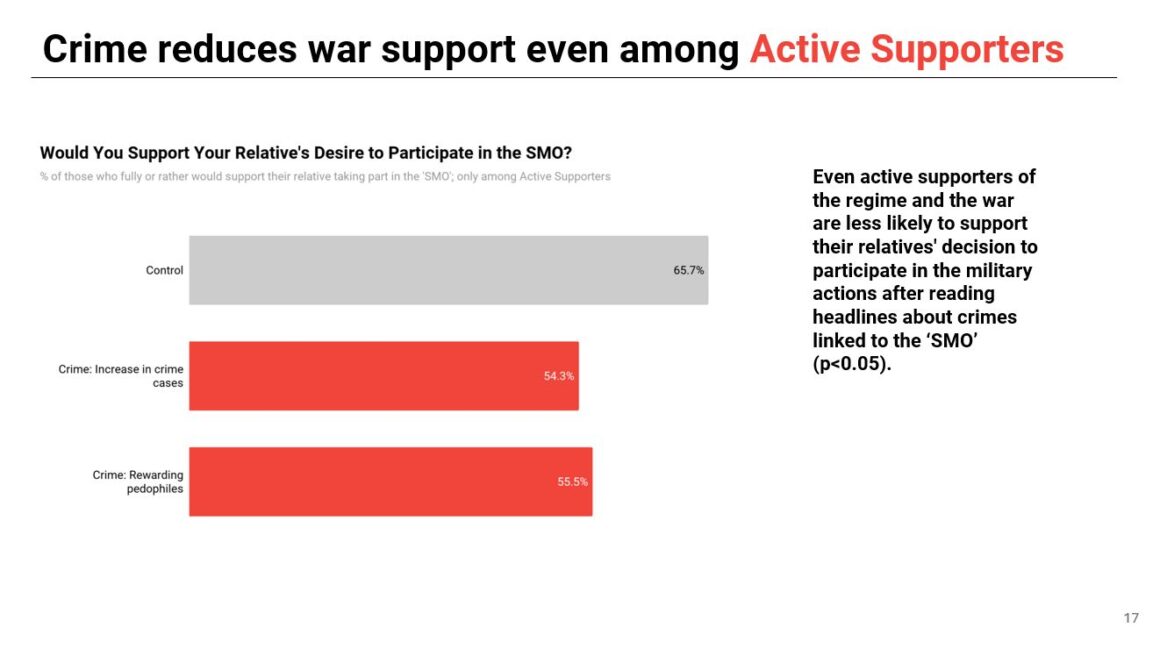

“Several research groups have found the same thing—that the most effective messaging is around the rise of crime rates in Russia to undermine the desire of people to send their families to the war,” Pomerantsev notes.

The crime messaging works because it targets what Putin supporters actually value:

- Order and stability – Rising crime rates suggest Putin’s “strong hand” is failing

- Personal safety – Stories about criminals in the army threaten families directly

- Elite competence – Military chaos reflects broader governmental failure

“People who support the war the most are very authoritarian. They want Putin’s strong hand. They want order,” Pomerantsev explains. “The idea that chaos is growing because of the war undermines their entire worldview.”

Why facts bounce off

Delmer worked with Cambridge’s first professor of psychoanalysis to understand Nazi psychology. They identified three elements that make authoritarian propaganda work:

- Identification with the leader – Leaders who normalize aggression, sadism, and narcissism, creating what Pomerantsev calls “a carnival of evil feelings”

- Toxic collective identity – A sense of superiority over others based on supremacism

- Ersatz agency – The illusion of control when people actually have none

“The less control we have over our lives, the more propaganda we need,” Pomerantsev quotes Delmer as observing.

This explains why showing Russians their casualties backfires. In an authoritarian mindset, those deaths demand vengeance, not reflection. Appeals to humanity assume a moral framework that propaganda has already dismantled.

“It’s not that he didn’t believe in facts. He just wanted to find the facts that worked for his aims,” Pomerantsev notes about Delmer’s approach.

The same principle applies today: effective counter-propaganda uses real information, but selects facts that serve strategic goals rather than moral ones.

“I don’t think there’s an important democratic movement in Germany to support,” Delmer concluded about Nazi Germany.

The same pragmatism should guide effective operations against Russia today. As opposed to the current Western strategy of supporting Russian opposition media, which can influence only 11% of critically-minded Russians, disruptive propaganda operations should focus on themes that resonate with authoritarian mindsets rather than moral appeals.

Pomerantsev’s research reveals the psychological mechanism behind this.

Working with teams in Russia, he found “the largest correlation between being ready to send your kids to die in the war is to do with belief in Russian supremacism”—the conviction that Russia is superior to others while simultaneously being victimized by them.

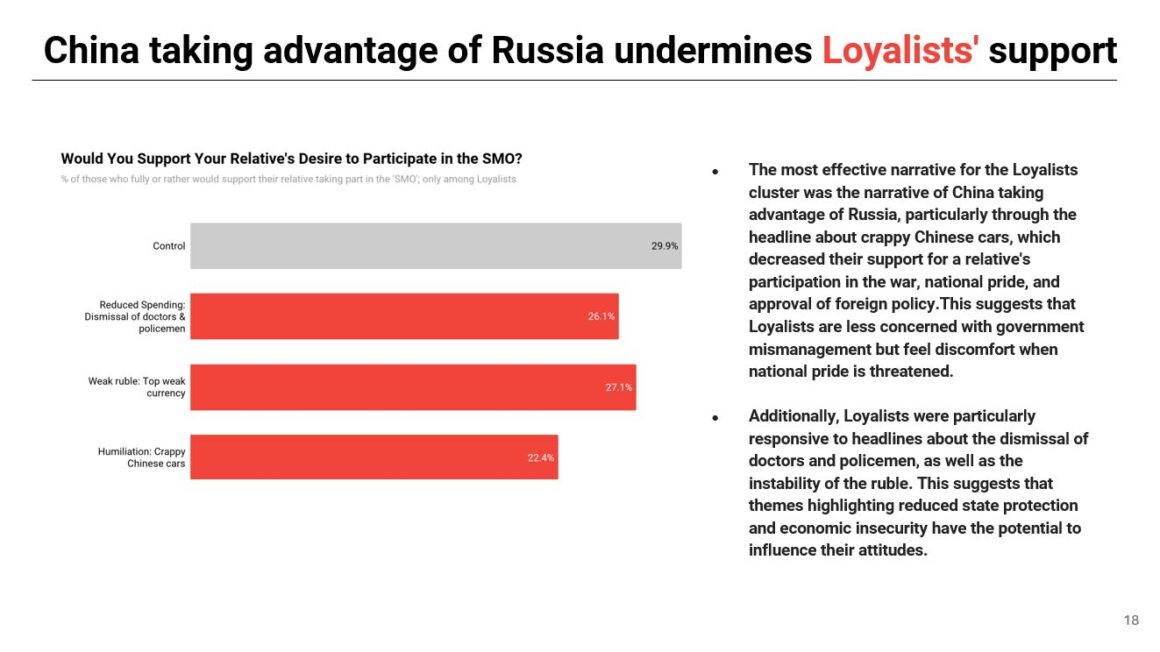

When Russians are primed with messages reinforcing this supremacist-victim narrative, their support for war actually increases. However, other messages do work: those hinting at rising crime inside the army and China humiliating Russia.

It is precisely these kind of messages that Ukraine is using in successful offensive propaganda operations against Russia, Pomerantsev suggests, hinting at the presentation of his book in Kyiv that the Delmers of today are sitting in the room, incognito.

The resource problem

The tragedy is that Ukraine knows what works but lacks the resources to scale it.

“Delmer had the backing of a state which allowed him to experiment,” Pomerantsev points out. “He had a team of hundreds of people working in this beautiful vast country estate outside of London. He managed to persuade the government to give him the most powerful radio transmitter in the world.”

Ukraine has no such luxury. While fighting for survival, it can barely manage domestic information space, let alone mount the massive multimedia campaign needed to truly destabilize Russian mobilization.

“If we were fighting this war as we did the war on terror, we would have set up dozens of radio stations like in Afghanistan,” Pomerantsev notes.

“We had huge information operations during our intervention in Iraq. If we were doing this, it would be such a key element of what we were doing. But we want to undermine mobilization, we say we want to slow down Russia’s war machine, and we haven’t done the ABCs of undermining mobilization and military morale. It just shows you how fundamentally pathetic Ukraine’s partners are.”

We say we want to slow down Russia’s war machine, and we haven’t done the ABCs of undermining mobilization and military morale.

The Kremlin’s real fear

What would work if resources were available? Pomerantsev outlines the pressure points that actually worry the Kremlin:

- Putin’s approval rating – Which collapsed to under 60% during Ukraine’s Kursk operation

- Economic stability – The ruble’s weakness, rising short-term loan defaults, a growing credit crisis

- Military compensation – Soldiers’ families not getting paid, creating resentment

- Elite loyalty – Growing mistrust between different power centers

- China’s reliability – Deep anxiety about Beijing potentially abandoning Moscow

“Any attempt to deter Russia has to be linked into their sense of control,” he argues.

The Kremlin’s leadership remains traumatized by how quickly the Soviet system collapsed. When they sense loss of control, they retreat.

The Kursk incursion proved this. Putin’s rating plummeted. The government panicked, posting and deleting contradictory messages. That was the moment to pile on pressure—NATO exercises, shadow fleet blockades, secondary sanctions. Add coordinated information operations targeting those specific vulnerabilities.

Instead, nothing.

Beyond good and evil

Delmer’s approach offends our democratic sensibilities. He promoted desertion, normalized corruption, used pornography to grab attention.

His radio shows were, by his own admission, an exercise in encouraging Germans to be “bad.”

Nazis told Germans they would be good by doing very bad things, while Delmer told Germans to be bad, achieving a very good thing.

“I think we have to think very carefully when we think about good and bad in politics,” Pomerantsev reflects. “If you’re stimulating someone to think for themselves, if you’re provoking them to act for themselves, if you’re provoking them to break through a kind of passivity which has been fed to them by authoritarian propaganda—I think that’s good.”

He sees Delmer’s work as fundamentally liberating:

“I think at the core of it was a deeply anti-authoritarian project because in stimulating people to think and act for themselves, he was giving them a way to break through authoritarian psychology.”

The Nazis used the language of nobility and sacrifice to enable genocide. Delmer used the language of greed and self-interest to stimulate individual thinking. When you’re deserting or stealing from your factory, you’re reclaiming agency from an authoritarian system.

As Pomerantsev puts it:

“The Nazis used the language of noble and the nation and sacrifice in order to enable genocide and rape, while Delmer was using the language of naughtiness, greed, corruption, sexual hanky-panky in order to stimulate good.”

The inversion is profound: Nazis told Germans they would be good by doing very bad things, while Delmer told Germans to be bad, achieving a very good thing.

This isn’t about making Russians good people. It’s about making them bad soldiers.

Radio then, full-spectrum now

If Delmer were alive today, he wouldn’t pick just one channel.

“We live in a multimedia age, so you need everything and you need scale,” Pomerantsev explains. “You’d be using radio, you’d be using satellite TV where it’s relevant, some of the great things the Ukrainians do—hacking into Russian local TV and playing content. You want all of those. You want to have a sense that you’re everywhere. Robo calls, SMSs, everything. You’re using everything and you’re thinking how they work together to create a full spectrum movement.”

The aim is the same as in the 1940s: make the people who keep the war going feel it’s no longer in their interest. Delmer did it by embracing the “baddie baddie” role. Pomerantsev is asking if Ukraine’s partners are ready to do the same.

As Pomerantsev puts it: “The Ukrainians are doing a lot, and I think, like with Delmer, we’ll find out after the war.”

The question is whether Ukraine’s partners will provide the resources for a real information offensive before it’s too late. Because knowing what works means nothing if you can’t execute it at scale.

Facts don’t defeat propaganda. But appealing to fear, greed, and self-preservation might. Delmer knew it. Ukraine has proven it.

The pig dog is waiting.