Why now? Ukraine just replaced its government mid-war — without an election

On 17 July 2025, Ukraine received a new government—the first full reshuffle since Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. The transition brought in a new prime minister, merged key ministries, and rebalanced power at the top of Ukraine’s wartime state. It was quiet but decisive—though not without raising eyebrows at home and abroad.

At the center of the overhaul is Yulia Svyrydenko, 39, who replaced Denys Shmyhal as prime minister. Shmyhal—who had held the post for a record five years—was appointed Minister of Defense, replacing Rustem Umerov, who in turn became Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council.

With the Cabinet now reduced to just 16 ministers, and several ministries merged or dissolved, it is one of the most compact governments in Ukraine’s modern history. The restructuring reflects not only a push for efficiency, but also a response to internal pressures and external scrutiny during wartime governance.

Under martial law, with no elections

The reshuffle was controversial not only because of its scope, but because of its legal context. Under Ukraine’s law on martial law, dismissing or appointing the Cabinet is explicitly prohibited, and elections are suspended indefinitely. The move was, at best, a legal gray zone.

It also raised concerns beyond legality. The opposition pointed to consolidation of power in the hands of the President’s Office. One well-known political joke was revived to express that fear: “It’s like rearranging the beds in a brothel—nothing really changes.” The point wasn’t just that the personnel might be the same—it was that the same people behind the scenes remain in control, with limited checks from outside the executive.

So why now? With no elections and wartime restrictions in place, the question of timing loomed large—and demanded an answer.

Delayed, not sudden

Political analyst Volodymyr Fesenko believes the change had been planned much earlier. “I think this is the implementation of a previously delayed decision. The reshuffle was already agreed in June, but it was delayed because the president had a full international schedule.”

Zelenskyy is known for periodic Cabinet changes.

“Last year, he didn’t replace the prime minister but changed half the government,” Fesenko told Euromaidan Press. “This time, the head of government was changed too. He rotates people when he feels something isn’t working.”

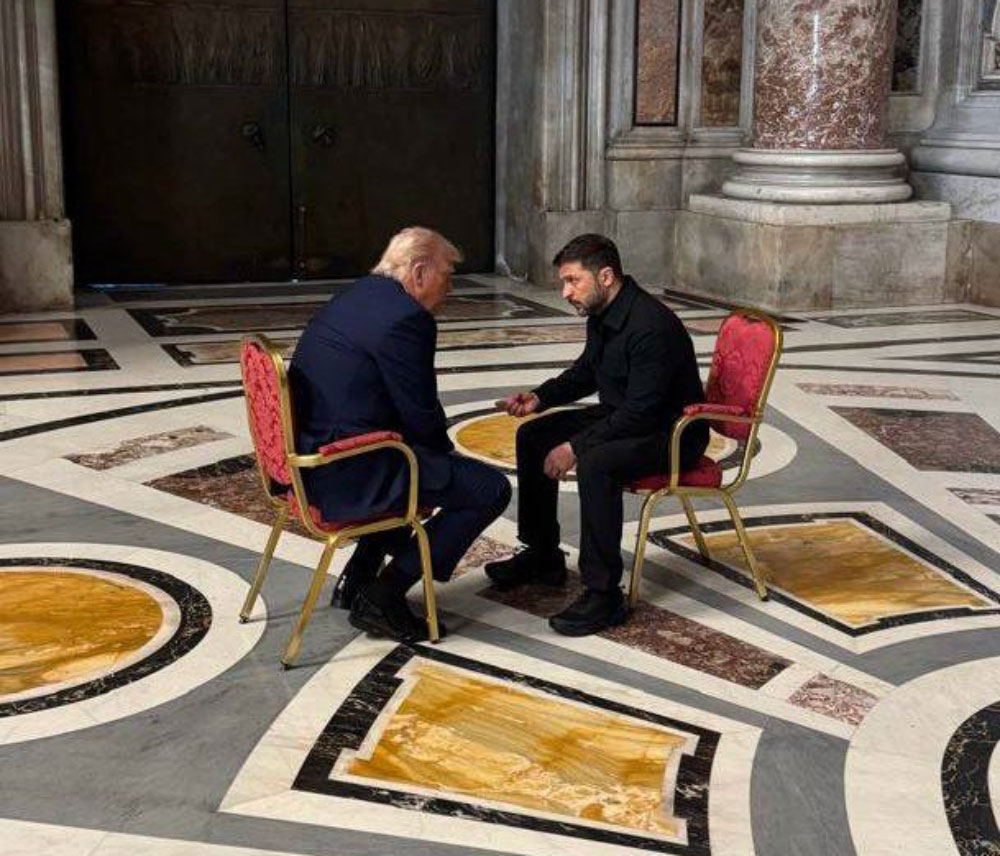

Another factor may have been Svyrydenko’s recent diplomatic success. According to Fesenko, she played a key role in managing sensitive economic negotiations with US counterparts related to the so-called “mineral deal”, helping to neutralize difficult political conditions. “That strengthened her standing,” he said.

However, Fesenko cautions against reading too much into a single cause. “There is no one particular reason for this reshuffle,” he said. “It is a combination of delayed plans, administrative adjustments, and political opportunity.”

Elections off the table

According to Ihor Chalenko, another political analyst, the government shakeup reflects growing consensus within the presidential camp that elections are not likely to happen any time soon. With martial law in place and war still ongoing, political updates must come from within the system.

“This is a reset without elections,” Chalenko told Euromaidan Press. “It signals change, rebalances power, and rebrands the government—without a vote.”

The timing allowed for a “reset” without major political risk—and provided a moment to address festering problems that had not been resolved by the existing team. The restructuring also comes amid increasing concern that Ukraine must refocus its executive branch to better coordinate diplomacy, economic recovery, and military production.

A calculated balancing act

Much attention has focused on whether the change represents a power play by Andriy Yermak, head of the President’s Office, over David Arakhamia, the leader of the governing Servant of the People faction. Svyrydenko is widely seen as a close ally of Yermak; Shmyhal had been backed by Arakhamia.

But according to both Fesenko and Chalenko, the final result reflects power balancing, not a power grab.

Fesenko acknowledged that tensions between Arakhamia and the president had been real, particularly about six months ago, when Arakhamia traveled to the US and presented himself as a potential point of contact with the Trump camp. “He told people he was arranging meetings, even with Giuliani. That really irritated the president. Since then, he’s stepped back.”

Chalenko emphasizes that the government as reshaped remains a coalition of internal power centers. “Take Mykhailo Fedorov,” he said. “He’s now First Deputy Prime Minister. And he’s had friction with Yermak. If this reshuffle was purely about consolidation, that wouldn’t have happened.”

The civilian part of the government—especially economic and social portfolios—is now clearly under the coordination of the President’s Office. But the military sector, particularly defense procurement and arms production, includes other political influences and interest groups that remain outside Yermak’s full control. According to Chalenko, this division is what keeps the new government politically “balanced,” despite external perceptions of top-down centralization.

Scandals as opportunity

While the reshuffle wasn’t caused by scandal, recent events made it easier to justify.

In June, Oleksiy Chernyshov, then Deputy Prime Minister — Minister for National Unity, was accused of abuse of office and receiving unlawful benefits on an especially large scale. He was released on ₴120 million (about $3 mln) bail. As Fesenko notes, this allowed for a smooth exit. “He’s gone, and so is his ministry. The moment was convenient.”

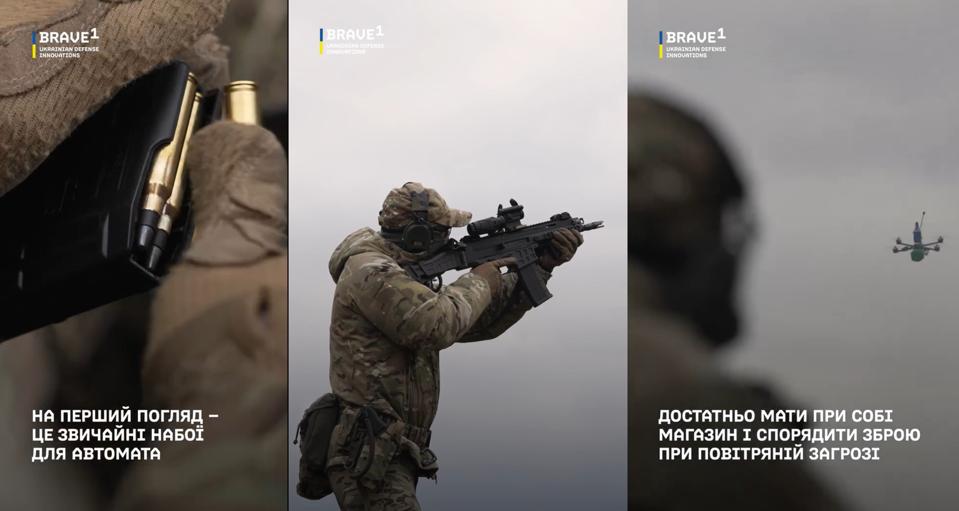

More serious were the problems inside the Ministry of Defense under Rustem Umerov. In late 2024, it emerged that mortar shells manufactured in Ukraine were defective. A public battle followed between Umerov and Maryna Bezrukova, head of the Defense Procurement Agency, raising questions of internal sabotage and political interference. NATO and G7 partners were said to be deeply concerned.

Fesenko called the situation “ministerial chaos.” He added: “Key professionals were sidelined. There was no clear strategy. Shmyhal was never a big political figure, but he was a very effective coordinator inside the government. Now he’s tasked with bringing that skill to the defense sector.”

Chalenko agrees, though from a different angle. He sees the appointment as “a mark of personal recognition from Zelenskyy himself,” noting that Shmyhal had preserved balance in the Cabinet throughout his unusually long term as prime minister. “That continuity is now being transferred to the defense sector—along with added responsibility.”

War economy, shrinking budget

The reshuffle also served as a vehicle for long-delayed administrative reform. Plans to merge ministries and reduce overhead had existed since 2023. Now, with fewer ministers and larger portfolios, implementation became politically possible.

The Ministry of Economy now includes portfolios previously managed by the agriculture and environment ministries, forming what some analysts describe as a “superministry” at the heart of civilian administration.

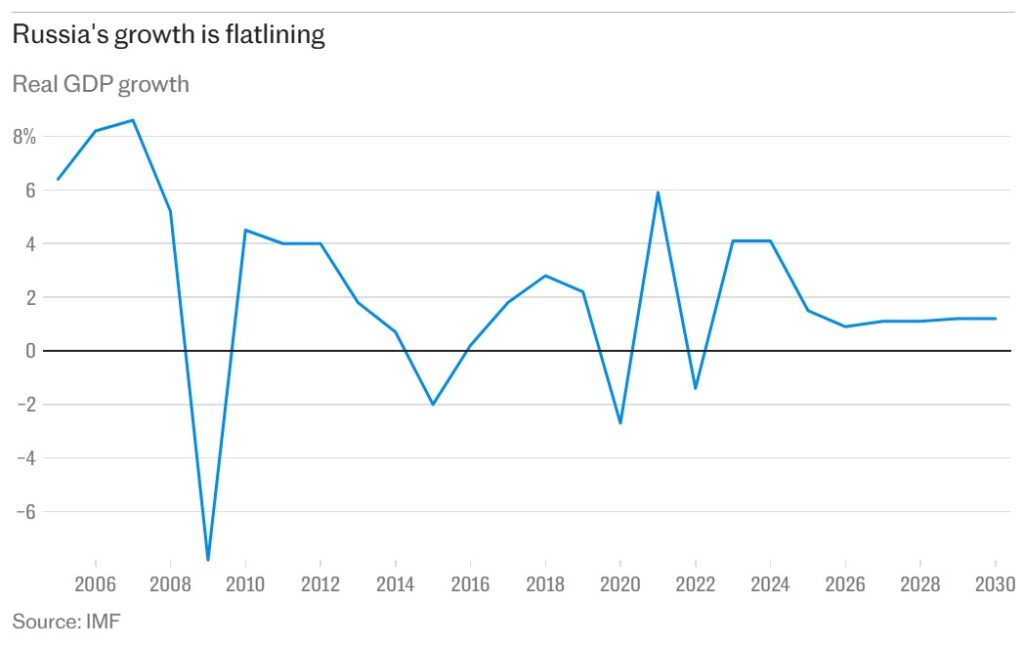

But perhaps most pressing: Ukraine’s economy is under enormous strain. With American budget support drying up, and European aid increasingly tied to complex conditions, the country faces rising deficits and mounting fiscal pressure. Stabilization is now a core priority.

In this environment, Svyrydenko is expected to focus on economic management. She is considered a trusted figure among Ukraine’s Western partners, particularly in financial and trade negotiations. But she will also need to confront deepening structural problems: declining industrial output, sluggish recovery in private investment, and ballooning social spending.

Fesenko said: “She knows what parts of the system can be influenced—and what parts are off-limits. That gives her some room in the economic sphere, where Yermak is less hands-on.”

A reset in wartime

Ultimately, the reshuffle represents a wartime recalibration. It allowed the president to respond to internal disorder, public fatigue, and Western concern—without elections, and without open crisis.

It is not a dramatic political transformation. But it resets the executive without destabilizing the system. As Chalenko put it, “the government remains balanced—and therefore, it can be called Zelenskyy’s government.”

Whether that’s enough will depend not only on Svyrydenko’s performance, but on how long the war—and martial law—lasts.

In effect, this reshuffle functioned as a reset without elections—a shift in power that maintains political control while responding to pressure for change.

Odesa, killing 2 and injuring 9.

Odesa, killing 2 and injuring 9. A rescuer carries out a smoke-inhaled 3-year-old as his mother runs behind.

A rescuer carries out a smoke-inhaled 3-year-old as his mother runs behind.