Italy’s concert for Putin is an ethical disaster, not a cultural event

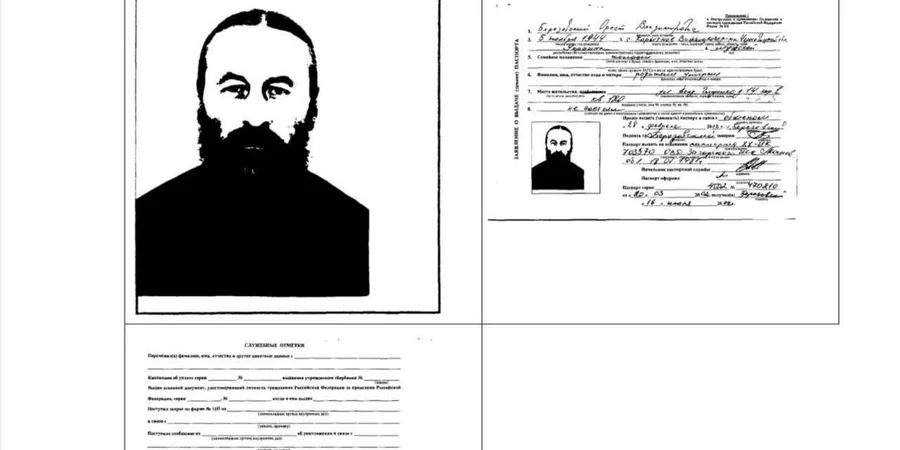

Valery Gergiev, the Russian conductor and longtime ally of Vladimir Putin, is scheduled to perform on July 27 at the Un’estate da Re festival in the Royal Palace of Caserta, Italy. Tickets are already on sale.

This marks his loud and controversial return to the European stage after years of exclusion due to his vocal support for Russia’s war against Ukraine — and, astonishingly, with the help of public funding, including European Union cohesion funds, despite the fact that Gergiev has been sanctioned in several countries.

But behind the mask of the great conductor lies something far more troubling. A recent Linkiesta investigation exposes a sophisticated network of shady foundations, fictitious companies, and significant real estate holdings spanning Venice, Milan, Rome, and the Amalfi Coast.

At its center sits a monumental estate in Massa Lubrense that allegedly hosts meetings aimed at circumventing international sanctions and diffusing Russian propaganda narratives through cultural interventions.

Where Gergiev is banned vs. where he’s welcome

Unlike Germany, the UK, the Netherlands, and Scandinavian nations — where cultural institutions severed ties with pro-Kremlin artists — Italy has chosen a more “tolerant” or “neutral” approach. Some even echo the favorite mantra of Russian propaganda: “Art is above politics.”

Here’s a reminder of where Gergiev has been banned:

- Germany: Fired from the Munich Philharmonic.

- UK: Removed from the Edinburgh Festival and other programming.

- USA: Canceled performances and tours.

- France: Banned from Théâtre des Champs-Élysées and other venues.

- Canada: Included in the list of individual sanctions.

But in Italy, Gergiev seems to be welcomed with open arms — all in the name of “cultural dialogue,” even as war crimes continue in Ukraine.

Putin’s conductor: A history of regime support

Gergiev, Putin’s most loyal cultural ally who received the specially revived Hero of Labour award in 2013, has never hidden his loyalty to the Putin regime.

He publicly praised the president, supported Russia’s “great revival,” and in 2014, endorsed the annexation of Crimea. That same year, he led a concert in Moscow honoring Russia’s armed forces.

After Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, cultural leaders around the world called for a boycott of Gergiev, accusing him of direct complicity in the Kremlin’s aggression. Major orchestras and opera houses in Europe and the US dropped him. In 2022, La Scala dropped him from its programming after he refused to condemn the war in Ukraine.

His appointment to control both the Bolshoi and Mariinsky theaters wasn’t just ceremonial — it followed the ouster of Vladimir Urin, who had dared to sign an anti-war petition in 2022, making Gergiev’s loyalty even more valuable to the Kremlin.

His fondness for dictators and warlords predates Ukraine. In 2016, following the Russian and Syrian military seizure of Palmyra, Gergiev performed a highly publicized “liberation concert” among the ruins. Broadcast widely on Russian state TV, the concert served as cultural propaganda to legitimize Moscow’s role in Syria and reinforce Putin’s image as a “defender of civilization.”

The €100 million Italian empire and sanctions evasion network

The financial mechanics behind his Italian operations reveal a more complex picture. As early as 2022, Alexei Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation documented that Gergiev had diverted over 300 million rubles into personal accounts, using cultural foundations funded by Gazprombank, Rosneft, and VTB.

Gergiev owns a real estate empire in Italy, reportedly worth more than €100 million, inherited from Countess Yoko Nagae Ceschina, a Japanese harpist and philanthropist. Her will granted him the Barbarigo Palace on Venice’s Grand Canal, the historic Caffè Quadri in Piazza San Marco, an 18-room villa in Olgiate, vast land holdings in Romagna, and a villa on the Sorrento Coast.

Recently, Italy’s famous Alajmo restaurant family renewed its rental agreement for Caffè Quadri — paying Gergiev €3.5 million over seven years. This means a sanctioned Kremlin-aligned figure is directly profiting from Italy’s most prestigious public spaces.

Massimiliano Coccia’s Linkiesta investigation reveals something more systematic: at least a dozen satellite companies orbiting around Gergiev’s main operations, spanning real estate, cultural, and logistics sectors across Campania, Lazio, and Lombardy.

Their common trait? Opacity. A portion of the revenue from these activities is reinvested into pseudo-cultural initiatives that bolster Russian propaganda.

EU funds for Putin’s ally

And now, in July 2025, Gergiev is scheduled to perform in Campania — at a festival funded in part by the Italian government, the Campania regional administration, the Teatro Verdi in Salerno, and Italy’s Ministry of Culture. It is officially branded as a cultural initiative supported by EU Cohesion Funds (Fondi Coesione Italia 21/27).

This makes any attempt to “normalize” Gergiev’s presence even more troubling.

Art as propaganda: The Bolshoi’s latest production

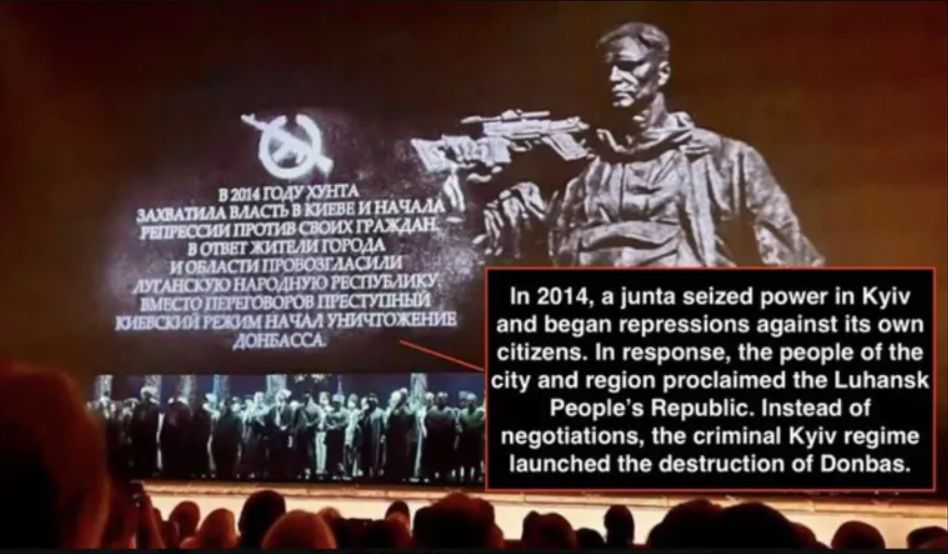

Gergiev himself constantly proves art isn’t neutral. Just this month, his Bolshoi Theatre closed its season with a production of Prokofiev’s opera Semyon Kotko that ended with a message glorifying Russia’s invasion of Ukraine:

“In 2014, a junta seized power in Kyiv and began repressions against its own citizens. In response, the residents of the city and region proclaimed the Luhansk People’s Republic. Instead of negotiations, the criminal Kyiv regime began the destruction of Donbas.”

Immediately following that, the next paragraph was projected:

“In February 2022, the Russian army came to the aid of the people of Donbas, who had been fighting for their lives and freedom for eight years. As a result of a nationwide referendum, Luhansk has forever returned to being part of Russia.”

This wasn’t art — it was state propaganda using opera as a delivery system, reversing historical facts to justify war crimes. As La Repubblica noted in its coverage, Gergiev’s own theater made it explicitly clear that the opposite of “art is outside politics” is true.

Why cultural neutrality during wartime is complicity

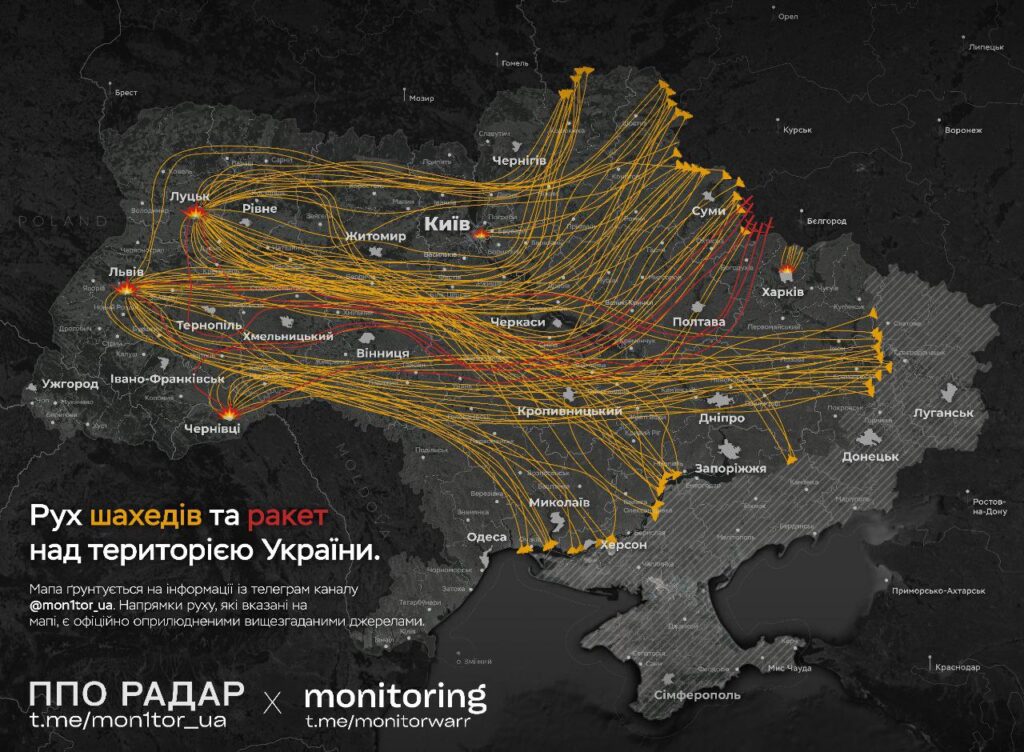

And now — after three years of genocide, missile strikes on residential buildings, torture and executions of prisoners, and mass atrocities documented by international bodies — this concert in Campania becomes part of a broader trend: the normalization of brutality through culture.

At this point, let’s be clear: art is never apolitical — especially during a war. We cannot ignore the fact that Valery Gergiev is not merely a world-class conductor, but a public ally of a regime internationally accused of war crimes. His return to the European stage is not a neutral cultural gesture — it is a political act.

Gergiev’s return to the European stage is not a neutral cultural gesture — it is a political act.

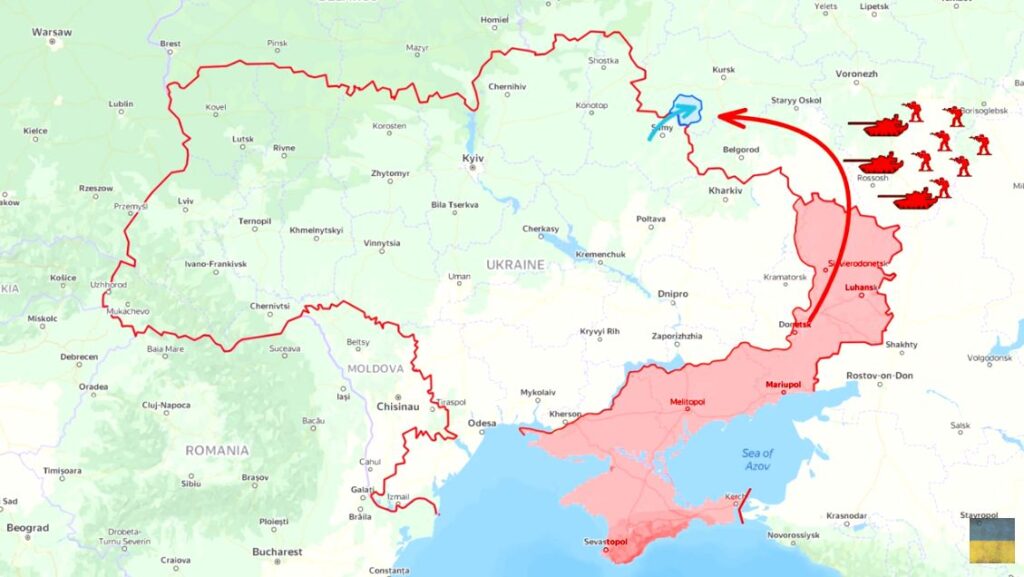

Yes, in peacetime, one might argue for “separating art and politics.” But in wartime — especially a war of conquest launched in 2014 and escalated into full invasion in 2022 — such neutrality becomes complicity.

Allowing figures like Gergiev — whose regime is bombing cities, deporting children, and jailing dissidents — to perform on publicly funded stages is not just tone-deaf. It is an ethical failure.

The unanswered question about local facilitators

Inviting Gergiev to Campania — with European funds — is a dangerous appeasement of Russia’s cultural offensive, which seeks to blur the line between art and propaganda.

As EU Parliament Vice President Pina Picierno rightly noted, publicly funding Putin’s allies is unacceptable. It sends the wrong signal — a signal of surrender.

While De Luca tries to mask this performance under the guise of tolerance, peace, and dialogue, Picierno confronts him with a point that is hard to refute: among the many equally famous and talented Russian musicians who have condemned the war, the Campania Region chooses Putin’s faithful friend and ally.

But the crucial question raised by investigators remains unanswered: which local entrepreneur or company proposed Gergiev’s engagement to the Campania Region? Who acted as facilitator for an event that showcases Russian power while a war rages?

The protests growing internationally

The announcement has ignited protests across Italy and abroad.

- Over 700 intellectuals—including Nobel laureates—signed an open letter declaring the event “a gift to the dictator.”

- Yulia Navalnaya, widow of the Russian opposition leader killed in a Russian prison camp, stressed that Gergiev is part of the regime that killed her husband.

- The Europa Radicale party launched its own petition and started buying tickets to bring protests inside the venue.

Italy’s Culture Minister withdrew approval for the concert, warning that using cultural platforms to amplify propaganda is unacceptable. Despite mounting criticism, the concert remains scheduled for 27 July, with the Caserta Police Headquarters monitoring the event through DIGOS (Italian Special Operations Unit).

There are fears that the protest, promoted by Ukrainian associations as well as Russian dissidents, could spill over into the Royal Palace. Many of the tickets for the front rows have sold out, and those who purchased them were representatives of Italian and Ukrainian associations, as confirmed by the president of one of these.

Deputy Prime Minister Antonio Tajani responded to criticism by noting that Gergiev holds a Dutch passport, so he can travel freely within the EU. The questions about how Gergiev obtained his Dutch passport while maintaining Russian citizenship have remained unanswered for almost a decade.

Russian state media celebrates the “return to Europe”

Russian state media is already hailing the concert as Gergiev’s triumphant “return to Europe,” claiming Italy will not cancel the event.

Once again, culture is weaponized. Since Soviet times, music, ballet, and the arts have been key tools of Kremlin messaging. The KGB had entire departments focused on shaping the regime’s image through culture.

This is not about freedom of expression. It’s about responsibility. Art can either support humanism or whitewash violence. When Gergiev conducts in war zones or imperial ruins, he’s not just waving a baton. He’s legitimizing state terror.

What message is Italy sending by supporting Ukraine politically, but welcoming Kremlin propagandists culturally?

When sanctions are among the few peaceful forms of pressure we have left, any cultural compromise becomes a form of complicity. Those who claim “art is above politics” must ask: above whose politics? Above human rights? Democracy? Solidarity?

And in the end — as always — it is the innocent who pay the price.

Editor’s note. The opinions expressed in our Opinion section belong to their authors. Euromaidan Press’ editorial team may or may not share them.

Submit an opinion to Euromaidan Press

InsiderUA/TG

InsiderUA/TG