Rich Gain and Poor Lose in Republican Policy Bill, Budget Office Finds

© Eric Lee for The New York Times

© Eric Lee for The New York Times

There are two options for criminals in a democracy who don’t want to go to jail. The first is to launch a large-scale campaign to legalise whatever crime it is that you want to commit. This is hard, slow, laborious and, in most cases, impossible. The second is to not get caught. This is not necessarily easy either, but it’s a lot easier when law enforcement agencies are small, embattled and under-funded.

The 300,000 or so financial institutions subject to regulations in the United States have to report any suspicions they have about transactions, as well as reports of large cash payments, to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network, or FinCEN. The idea is that their reports will alert investigators to crimes while they’re going on, and help the goodies catch the baddies.

DEFUNDING THE COPS

Sadly, however, FinCEN’s computer system is so clunky it’s like, as a former prosecutor once said, trying to plug AI into a Betamax. Investigators often have to create their own programmes to trawl a database that gains more than 25 million entries every year, or else just pick through them in the hope of finding something interesting. It effectively means that this vast and priceless resource is hardly ever used.

And now FinCEN’s budget looks like it will be slashed even further. “The pittance allocated to FinCEN in the current budget has been reduced even further,” wrote compliance expert Jim Richards, with a link to the 1,200-page supplement to the White House’s proposed 2026 budget with details about the cut. The reduction would take spending back to 2023 levels, which is worrying for anyone keen on seeing criminals stopped. And that’s even before you take into account the effect of workforce disillusionment at regulators such as the Securities and Exchange Commission, resulting from the cuts imposed by DOGE.

“I experienced some dark times during my SEC career, including the 2008-09 financial crisis and the Enron and Madoff scandals,” wrote Martin Kimel in a passionate column in Barron’s. “ But morale at the Commission is the worst I have ever seen, by far. No job is secure. Nobody knows what will become of the agency or its independence.” So, he added, “when the SEC offered early retirement and an incentive payment for people to voluntarily resign, I and hundreds of others reluctantly accepted.”

If you lose experienced personnel, and you lack the resources to invest in the latest technology, you will always lose ground against entrepreneurial and skilled financial criminals. That is the inevitable consequence of what is happening in the United States, which will be devastating for the victims of fraudsters, crooks, hackers and more.

THE UK PRECEDENT

There is, however, a cycle to this kind of thing. Governments that are determined to unleash the private sector always cut enforcement of regulations, but then they become embarrassed by the inevitable revelations of corruption, sleaze and incompetence that result. This is what happened in Britain, where years of news headlines about London being the favourite playground of oligarchs finally led to government action.

Three years ago, the British authorities imposed a special levy on financial institutions to fund the bodies that fight crime, and last month it published a report on the first year of spending. More than 40 million pounds has been invested in new technology to tackle Suspicious Activity Reports (so no more Betamax in London), and almost 400 people have been hired to do the work, including some of them finally beginning to try to drain the swamp that is the U.K.’s corporate registry. This is good news.

It is inevitable that, just like in the U.K., the United States will eventually become so appalled by the rampant criminality that will result from the cuts to FinCEN, the SEC and other bodies, that politicians will start building a decent system to stop it. I just wish everyone would get on with it, so millions of people don’t have to lose out first.

THE EU GETS INTO GEAR?

You can accuse the European Union of many things, but you can’t say that it acts hastily. Several months after the last progress update from the Anti-Money-Laundering Agency (AMLA), it has appointed its four permanent board members. They represent an interesting cross-section of European expertise.

There’s Simonas Krėpšta who, at the Bank of Lithuania, has overseen the country’s booming fintech sector and, therefore, has a good insight into the country’s booming money laundering sector, which has seen quite a lot of firms get fined, including arguably Europe’s most valuable startup Revolut.

Then there’s Derville Rowland of the Central Bank of Ireland, who will bring inside knowledge of Europe’s most aggressive tax haven. And Rikke-Louise Ørum Petersen, who joined Denmark’s Financial Supervisory Authority in 2015, just when the money laundering spree by Danske Bank was about to explode into public view. Finally, there’s Juan Manuel Vega Serrano, who was previously head of the Financial Action Task Force, which gives him plenty of experience of working at an ineffective, slow-moving, superficially apolitical, supranational anti-money laundering organisation.

All told, I’d say this is a pretty perfect group of people for the job. The European Union works slowly, but it works thoroughly. Of course, AMLA won’t actually be doing anything until 2028, and it probably won’t do much after that either. But you can’t have everything.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Oligarchy newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Creating a culture of corruption appeared first on Coda Story.

© Erin Schaff/The New York Times

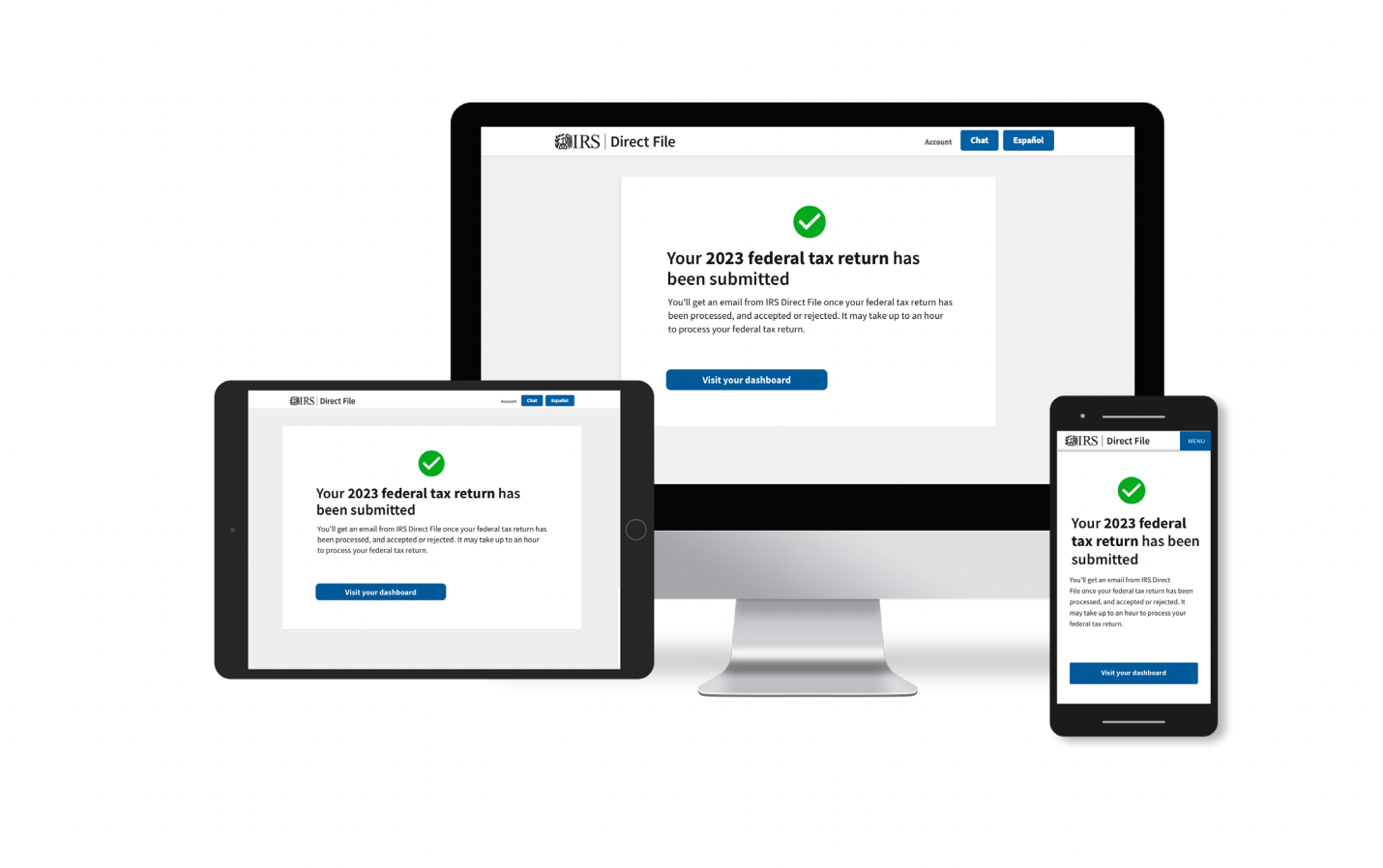

The IRS open sourced much of its incredibly popular Direct File software as the future of the free tax filing program is at risk of being killed by Intuit’s lobbyists and Donald Trump’s megabill. Meanwhile, several top developers who worked on the software have left the government and joined a project to explore the “future of tax filing” in the private sector.

Direct File is a piece of software created by developers at the US Digital Service and 18F, the former of which became DOGE and is now unrecognizable, and the latter of which was killed by DOGE. Direct File has been called a “free, easy, and trustworthy” piece of software that made tax filing “more efficient.” About 300,000 people used it last year as part of a limited pilot program, and those who did gave it incredibly positive reviews, according to reporting by Federal News Network.

But because it is free and because it is an example of government working, Direct File and the IRS’s Free File program more broadly have been the subject of years of lobbying efforts by financial technology giants like Intuit, which makes TurboTax. DOGE sought to kill Direct File, and currently, there is language in Trump’s massive budget reconciliation bill that would kill Direct File. Experts say that “ending [the] Direct File program is a gift to the tax-prep industry that will cost taxpayers time and money.”

That means it’s quite big news that the IRS released most of the code that runs Direct File on Github last week. And, separately, three people who worked on it—Chris Given, Jen Thomas, Merici Vinton—have left government to join the Economic Security Project’s Future of Tax Filing Fellowship, where they will research ways to make filing taxes easier, cheaper, and more straightforward. They will be joined by Gabriel Zucker, who worked on Direct File as part of Code for America.

Since Donald Trump returned to the White House in January, some 31 percent of “revenue agents” (the people tasked with conducting tax audits) have lost their jobs. This is supposed to save the government money, but it’s a bit like trying to reduce the cost of crime by sacking police officers.

“This administration is clearly running the risk of losing hundreds of billions of dollars -- in fact, likely over $1 trillion -- through its destruction of the IRS. “At a time when deficits are high and rising, that seems a baffling policy choice,” said Larry Summers, noted economist, former treasury secretary, and former president of Harvard University.

The policy is indeed baffling if its aim is to collect taxes; it’s not baffling at all, though, if the intention is to help rich people dodge them.

Subscribe to our Coda Currents newsletter

Weekly insights from our global newsroom. Our flagship newsletter connects the dots between viral disinformation, systemic inequity, and the abuse of technology and power. We help you see how local crises are shaped by global forces.

An early announcement from Trump’s Department of Justice was to pause enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, which has been central to global efforts against bribery since the 1970s. Trump has long argued that prosecuting American businesses for bribing foreign officials makes it harder for U.S. companies to compete. A new DoJ memo shows that it has now thought about what it wants to do, and how to do it in a way that prioritises American interests.

There have long been suspicions that U.S. authorities reserve their biggest fines for non-US companies (a French bank getting fined almost $9 billion, for example), and suggesting that prosecutions will be “America first” is unlikely to help with that perception. “Enforcement of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act ("FCPA") will now be focused on conduct that harms U.S. interests and affects the competitiveness of U.S. businesses, further suggesting that future FCPA enforcement will be focused on non-U.S. companies,” noted lawyers from White&Case in this assessment.

There is already widespread global concern that the Trump administration will exploit the U.S. dollar’s dominant position in finance to force foreigners to do what it wants. Suggestions that corruption laws are not equally enforced will only further that suspicion. The fewer foreigners who rely on dollars, the less impact US sanctions will have, so it would be good if officials would consider that before implementing their policies.

MINDING THE TAX GAP

Readers old enough to remember the financial crisis of 2007-8 will also remember the wave of popular anger against tax-dodgers that followed it. American prosecutors investigated Swiss banks (good times!); protesters occupied branches of Starbucks (fun!); almost all countries agreed to exchange information with each other about their citizens’ tax affairs to uncover cheats (massive!).

According to the EU Tax Observatory, this information exchange has been a triumph, and cut wealthy people’s misuse of offshore trickery by two-thirds. I have always been a little suspicious of these declarations of victory, however, despite them coming from such a good source, and find grounds for my doubts in this new report from the UK’s National Audit Office.

British tax authorities every year estimate a tax gap – the difference between what the country’s exchequer should receive, and what it actually gets – and politicians regularly talk about reducing it. If the Trump administration seems uninterested in clamping down on tax evasion, and financial chicanery in general, the British government has pledged additional resources for technology and investigators to try to understand what’s happening and whether its tax gap estimate is close to being accurate, so we may learn more about this in future years. Fingers crossed.

But the NAO report suggests that the way it’s calculated may be a bit questionable. According to the standard estimate, wealthy individuals pay around 1.9 billion pounds less than they should. But, according to a different estimate (“compliance yield”), the tax authorities have successfully brought in an extra 3 billion pounds from wealthy people that would not have been collected without their efforts.

It is a little hard to understand how it is possible to increase tax compliance by 1.1 billion more pounds than the entire deficit that wealthy people are supposedly underpaying. It’s like losing two pounds down the back of an armchair, reaching beneath the cushion and finding three. Except with billions. Something else is very definitely going on. “The large increase in compliance yield raises the possibility that underlying levels of non-compliance among the wealthy population were much greater than previously thought,” notes the NAO.

I am, I admit, someone who fixates on offshore skulduggery, but I can’t help noticing the report states that a mere five percent of the UK tax authorities’ investigative efforts were looking into “offshore non-compliance”. Tax advisers are clever, well-paid people, and they’ll know very well about the best places to hide their clients’ money, and there’s even a suggestion for them in the report: if your client holds wealth in properties abroad, or owns shares in her own name rather than through an institution, her home government will never know about her income she earns from them. Happy days.

A POSTER CITY FOR ILLICIT FINANCE

And speaking of offshore skullduggery. The city of Mariupol has long been central to the war in Ukraine. Enveloped early by Russian forces, its defenders held out for months in an epic battle in the ruins of the Azovstal steel plant, before surrendering in May 2022. Moscow has since made it the poster city for the supposedly prosperous future available in a Russia-ruled Ukraine, but a new report makes clear how hollow such claims are.

“Powerful Moscow-based networks are controlling much of the reconstruction programme. Well-connected companies are benefiting from Russian spending that involves the widespread use of illicit finance and corrupt practices,” note its authors, David Lewis and Olivia Allison. They have specific policy recommendations, of which I think the most important ones relate to my old bugbear of sanctions, which should be better targeted and more strategically deployed. Russia’s crimes in Ukraine include the looting and economic exploitation of cities like Mariupol.

A version of this story was published in this week’s Oligarchy newsletter. Sign up here.

The post Making America corrupt again? appeared first on Coda Story.